by Philippe Goudard, Wei Liang, Marisa Ribeiro Soares et Rafael Resende Marques Silva

Laughter is a universal anthropological phenomenon. Each culture has its own people who make us laugh, with different modalities and purposes. The commonalities are as numerous as the nuances between the comic's expressions.

The universal clown

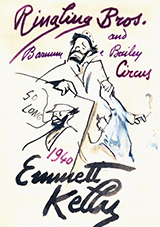

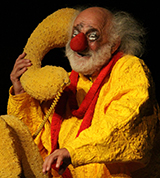

Born in Europe in the 16th century, this is a global figure to be found all over the world. Alternating between refined and rustic – the clown and the Auguste – or cinematographic, several mutations have led to a more stable development. A clown can be any artist or person whose behaviour, voluntarily or unknowingly, triggers laughter. The term has even become part of everyday language: "what a clown!"

The Western clown is the expression of a culture, a state of being in the world interacting with an era, a thought, a political history. Contemporary to the emergence of private property and capitalism, the unique figure of the clown is the aesthetic result of a historical process that aligns him with the commercial and urban culture. The various expressions used today meet the needs of the cultural and entertainment industries, advertising and consumption, educational, therapeutic or social mediation. Western culture has retained the initial bipolarity of the figure, between those of the joker and the tramp.

Designable and identifiable by all, the character has a name, a behavioural pattern, a silhouette. Elegant, pale and worrying in the tradition of Joseph Grimaldi, it is most often reduced today to a red nose inherited from the congested face of the alcoholic or the peasant, the mask of the Auguste, but also from the comic strip and the cartoon. It swings between the playful or manipulative intelligence of a white clown or a fool (Francesco Caroli, Raymond Devos, the joker) and one who is made fun of for his candid ignorance. The clown then returns to childhood and its most tender, dreamlike and even metaphysical part (Buster Keaton, Charlie Rivel, Dimitri, Slava Polounine) but can also be reassuring (the Clowns Doctors, Clowns Without Borders) or attractive (Ronald MacDonald).

And last but not least, tragic or frightening, is the dominant figure of the excluded. Misfit, unsettled outsider, poor but dignified (Charlot, Yuri Nikulin, Otto Griebling) we mock him; deformed, eccentric, monstrous, he bothers us (Coluche); malevolent, we fear him (It). Antonymous with wealth, beauty and success, it is then a representation of the difference where codified stage productions provide an opportunity for integration and conjure up the anguish of an entire society: failure.

Comic roles in China: from Paiyou to Xiaochou

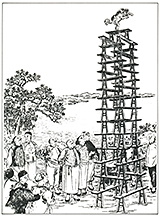

Several non-European cultures have also formalised the production of laughter. In China, the comic role is an essential figure in Chinese acrobatics (Zaji) and Beijing opera.

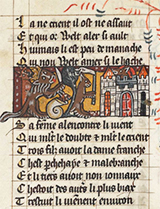

俳优 Paiyou:Zaji's comic figure

In China 杂技 (Zaji) which is translated into French as "acrobatics", refers not only to this discipline but also to a whole range of performing arts with a thousand-year history. Present since the emergence of Chinese acrobatics under the Qin dynasty (221 -206 BCE), comedy played a very important role under the Han dynasty (202 to 220 BCE), where Chinese acrobatics are a complete and varied form of entertainment art, this is the Hundred Games: ground or aerial acrobatics, juggling, dressage, and the most diverse tricks and performances: dances, fights, illusions, and comedic play.

The comic actor is called 俳优 (Paiyou), a name that means "that relieves pain". He appears during celebrations, meetings and other leisure activities. He plays for the emperor and the public, provokes laughter with ironic and buffoonish performances. He dances or tells stories to the rhythm of the drum. He is also present in the form of funeral statues, which were very popular at the time.

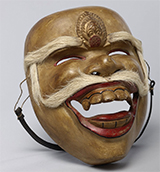

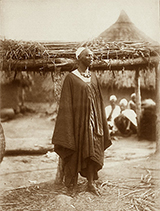

Ritualistic laughter

Linguist and semiologist Paul Bouissac, after forty years of field observations on professional clowns in Europe, the Americas and Asia, describes in Java the Punakawan, interrupting the ritualistic tale of Ramayana with ironic comments and idiotic jokes. He regards the art of clowning as a "secular ritual" (Bouissac, 2015, 81). Ethnologists have observed different cultures where ritualistic practices seek to produce laughter. Eric Smadja (1993, 83-123) lists them: the Brazilian Nambikwara studied by Claude Levi-Strauss, the Hopi Indians of North America by Don Talayesva, the Guayaki of Paraguay by Pierre Clastres, the Samoans by Margaret Mead, the nomad Bedouins in Arabia by Wilfred Thesiger, the Mnong of South Vietnam by Georges Condominas and the Iks in Uganda by Colin Turnbull.

Laughter priests

The Heyokas, North American Indians, are men of contrasts: they do everything backwards to heal the illnesses of their community through laughter, in dances and rituals using a logic of inversion: "A Heyoka has a strange behaviour. He says yes when he means no. He rides his horse backwards. He puts on his moccasins or boots the wrong way. In winter when the temperature drops below minus forty, he puts on a bathing suit and announces that he is going for a swim to cool down a little..."

John Fire Lame Deer (Tahca Uhste), a Lakota Indian, who translates Heyoka into English by the word clown, explains in his book: "For us, a clown (Heyoka) is a sacred, funny, powerful, ridiculous, holy, shameful, visionary being. He is all this and much more. By acting like an idiot, he is actually performing a ceremony." [John Fire Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes, De mémoire indienne : en quête d’une vision, Bénaix, Éditions Présence Image & Son, translation Jean-Jacques Roudière, 2009. p. 340].

The Hotxuás, Indians of the Krahô tribe in northern Brazil, have the task of bringing the community together with joy. They are "laughter priests" who entertain the community. They also use a behavioural inversion code. The face and sometimes the body are symbolically made up in red, black and white make-up, considered sacred, the Hotxuás represent an element of balance for the Krahô. In search of laughter in everyday life, offering the possibility of seeing life from other angles, they contribute to the social structure of the tribe, as shown in the film Hotxuá. [Cardia, Gringo and Sabatella, Letícia, Hotxuá, Brazil, 2009]

The Trickster

The extreme media coverage of the Western model sometimes leads to the naming of singular expressions of the comedian as clowns, although they are very different in their forms or functions, because they are not intended for the production of shows. The term "sacred clowns" then refers to a phenomenon outside Europe in a way that may appear ethnocentric and that could be prevented with a more precise terminology. The connection between the clown and the Trickster is just one such example.

Paul Radin, anthropologist1, Carl Gustav Jung, psychologist and Charles Kérény, mythologist2, studied the cycle of the hero Wakdjunkaga whose function is to "play tricks" in the mythology of the Winnebago tribe in North America3. It is an expression of the archetype of the Trickster or "divine rascal", "deceiver, cheat, perfect scoundrel or congenial rogue4", which exists in many cultures and conveys representations of good and evil, of order and disorder. He is a "violator of values both creator and destroyer5" at the same time "hero and buffoon6", a "situation invertor7".

These researchers use the word "clown" to refer to this social disruptor, but without referring to the entertainment world. A certain confusion has thus crept into the search for the origins, an archetype or a mythical figure linked to the clown, who then appears as an avatar of the trickster. But this thesis is still being argued over. Paul Bouissac[2015] notes that if there are obviously some similarities between the properties and functions of the clown and those of the trickster, the "white" who plays tricks and the transgressive Auguste for example, the contemporary figure of the clown, which combines the two properties, and that of the trickster, would be avatars of the same social identity. For him, the cultural link between the trickster and the clown is pending further research, still at the speculative stage, and a stimulating hypothesis.

Cultural Coincidences

Nowadays a generic name and part of the collective imagination, the clown, like his cultural neighbours, now appears as the synthesis of what is laughable. Present in the rites or their secular transposition on stage, in the ring, on the screen and in mass communication, its function is to stimulate comedy through play in ways that are admissible and can be integrated into society as a whole. There are many similarities between different cultures.

The clown transgresses, crosses boundaries, pushes the established order, disturbs, creates disorder, turns the world upside down (Deonna, 1958). He produces an organised chaos according to a socio-cultural ritual codified in a dynamic relationship but paradoxically subordinated to religious or economic political power. The inadmissible put into play is reinstated, reinjected into what is permissible within society. Yes, if it's a codified game. No, if the transgression destroys all codes. Yes to the artist or performer playing the fool, no to the fool at all. Ctibor Turba with the clowns of Circus Alfred, or Slava Polunin with Zia, are the symbols of " everything is allowed " at the heart of political coercion.

Through their art, transgression is permitted. The buffoon becomes a hero.

1. Paul Radin, The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology, New-York, Schocken Books, 1956.

2. Charles Kérény, Le fripon divin, un mythe indien, Genève, Librairie de l’Université Georg, 1958.

3. Rafael Resende Marques da Sylva, Approche théorique et pratique de la création et la pédagogie clownesques. Un voyage entre Brésil et France, thèse, Montpellier 3, France, juin 2018.

4. Claude Levi-Strauss, in Michel Panoff, Michel Perrin, Dictionnaire de l’ethnologie, Paris, Payot, 1973.

5. Laura Makarius, Le sacré et la violation des interdits, Paris, Payot, 1974, p. 16.

6. Brian Street, "The trickster theme: Winnebago and Azande" in Zande themes, Totowa, Rowman and Littlefield, 1972, p. 85.

7. William Hynes and William Doty, Mythical trickster figures: contours, contexts and criticisms, Tuscaloosa, The University of Alabama press, 1997, p. 8.