by Nathalie Vienne-Guerrin et Philippe Goudard

The origin of the clown is often to be found in the circus, where he built a universal identity after the birth of this show at the end of the 18th century. However, the clown appeared in England two hundred years earlier.

The emergence of the clown

Victor Bourgy calls the "emergence of the clown" the emergence of a word and a theatrical figure on the stages of the Elizabethan playhouses around the 1590s.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the term clown appeared in England in the second half of the 16th century and refers to a character, a job and an acting speciality. The lexical analysis shows that he is sometimes the clown of the fields, the rough-hewn commoner. Linked to the term clot, or clod, which refers to a clod of earth, it refers to the country boy, the yokel, the peasant, the rough-hewn commoner, the oaf, the man who has no manners, which gives an idea of the negative connotations associated with the figure of this rustic clown. He is by extension associated with stupidity. But he is also the clown of the cities: the headliner. And the term clown also very quickly refers to the comic actor who holds a special place in the Elizabethan theatre, both a member of the troupe and a free electron, to whom the playwright reserves a specific space of play and for whom he writes comic roles of clown, fool or jester. The word clown is therefore also a technical term from the professional world of theatre. But when it appears in the script of the play, it assumes the meaning of the peasant character, of the rustic, what the Elizabethans call a country clown.

The clown and the fool

The clown is rustic, while the fool is refined, the clown is from the countryside, while the fool is from the cities, the clown is body while the fool is spirit: the types of the future 19th century clown comedy are already present on the Elizabethan scene.

However, the titles of the works written by Elizabethan clowns, as well as the critical and historical works that explore the figure of the clown in Elizabethan times, reveal a scrambling and a blurring of the lines between fool, jester and clown. This mixture reflects the porosity of the boundaries, when it comes to the clown, between character and actor and between different figures and comic modes that the clown seems to catalyse.

Elizabethan clowns between body and mind

Elizabethan clowns fluctuate between blundering and verbal refinement, between physical performance and finesse of mind.

Will Sommers, clown in the Tudor period, famous jester of Henry VIII's court, ranks among the "artificial" clowns rather than the "natural" jesters, in other words, he is not simple-minded as such but talented as an artist. He is known for his mind games more than for his physical exploits.

Richard Tarlton is identified as the first theatre clown. He joined the King's Men troupe in 1583. Tarlton is known for his coarse physique and for his jigs, popular sung and danced interludes that combined improvisations, music and clown acts, often farcical and obscene, that were often used to close a show and that could change the tone at the end of the play. The clown Tarlton plays the country man transposed to the city, who takes a distant look at urban life. He thus embodies the two meanings of the term clown, the rough-hewn commoner and the star actor. In the 1580s, Tarlton introduced his style of the man associated with beer and taverns to the theatre, which was an innovation that explained his success and linked him, for some critics, to the character of Falstaff.

William Kemp, a famous Elizabethan theatre actor, is one of the founding members of the Lord Chamberlain's Men and continues the tradition of the rustic clown in the 1590s. Kemp, an excellent dancer, is also celebrated for his jigs that left their mark in the minds of the audience. Most of these roles are based on coarse and poor language and physical games. It is possible that the disappearance of the character of Falstaff in Henri V was due to the departure of Kemp in 1599, who was replaced by a new clown of another genre, Robert Armin. Thus, the passage in which Hamlet blames the clowns for their excessive improvisations (Hamlet, 3.2) can be read as a denunciation of Kemp's style, now considered too coarse to serve the subtleties of the Shakespearean text.

Robert Armin began his career with Tarlton and succeeded Kemp on the Shakespearean scene in 1599-1600. With Armin, the clown becomes a more subtle figure in roles where the mind prevails over the body. Among the main actors of Shakespeare, he plays the roles of wise fools but, as an excellent singer and author, he writes his essay on "the kinds of fools", Fool upon Fool (1600), and contributes to the evolution of the clown into more intellectual fools roles where word plays and mind games prevail over physical acrobatics.

Before the clown: ancestries and proximity

There is therefore a before and an after point after the appearance of the name and figure of the clown in the 16th century, which should only allow the use of the term after that date.

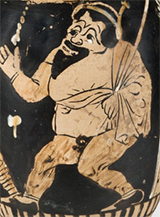

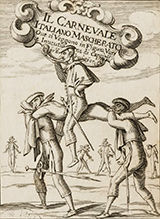

Many clown genealogies exist in which he is linked to previous figures. In the Western European branch, the names include Bromios the turbulent, one of the manifestations of Dionysus, the actors of the satyric drama, the transgressive servants of Aristophanes' comedies, the masks of the Roman atellanes and the valets of Plautus' comedies, among others, the protagonists of ritual inversion celebrations and carnivals, the fools of the sotties, the jesters and jokers, the court fools, the stage fools, the devils of medieval and Renaissance mysteries and morality and their valet, the Vice. We also meet the zannis of the commedia dell'arte or Harlequin, whose contemporary emergence, comic function and servant status make them cousins of the clown. But establishing this ascending genealogy of the clown so often related would require that linguistic or formal filiations can be established with certainty, which is particularly delicate in practice.

Some people associate the clown with jesters, probably for his grotesque and ridiculous ways, his codified travesties and transgressions producing laughter during the carnival, where it is possible to transcend the taboos, overstep the rules and feign madness (etymologically the jester is the one whose bloated cheeks deform the face; madness means the one whose head is "full of wind").

A proximity is proposed with the fools, satirists playing "sotties" in 16th century Paris, political pieces that postulated that society is composed of fools. They wear hats with donkey ears. The sotties are given at the same time as the farces and moralities where the Evil One, according to an invariable scenario, as a bawdy and transgressive jester, tries to turn such or such holy man or woman off the right path and leads them towards the deadly sins, allowing the Virgin to save them in extremis from hell in the end. In British moralities this disturbing and comic character is the devil's valet: The Vice.

The fool is close to the clown. First exhibited for his deformities in private collections of curiosities for the amusement of princes, the court fool is a laughter professional. Authorised to all kinds of disturbances provided that he amuses and flatters the power within the strict limits granted to him, his function is to say aloud what is usually kept silent, he has all the necessary licence, at the discretion of the Prince, and at his own risk and peril. Many are remembered, L'Angély under Louis XIII and Louis XIV, Brusquet under Francis I and his successors, Archibald Amstrong under Jacques I, a woman, Jane The Foole under Catherine Parr, Mary I, and Triboulet under Louis XII and François I, which Victor Hugo then Giuseppe Verdi and Nicolas Piave also used to challenge the power and censorship.

Finally, some formal coincidences and similarities can be used to argue in favour of a persistence and continuity of the symbolism of these different figures in the clown. The donkey ears and rooster crests (coxcombs) that adorn the hats of jesters, fools and madmen, the bells attached to their headdresses or their members for carnival celebrations or Morris dancing, are also present on the costumes of the clowns of the Elizabethan theatre and to this day.

Their symbolic and sexual functions, signs of physical and psychological effervescence, are perpetuated even in the most contemporary forms of clowning.