by Pascal Jacob

The history of the modern circus, begun in the second half of the 18th century in England, can be broken down into five major periods that correspond to developmental phases, and are characterized by artistic and technical transformations that enable one nation, rather than another, to establish itself in terms of the influence it has, well beyond its borders. The first of these periods was, naturally, English.

1770-1830: The pioneers

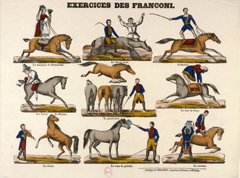

Between 1770 and 1830, British citizens Philip Astley (1742-1814), Charles Hughes and John Bill Ricketts, were the pioneers of adventure. They established the circus respectively n France, Russia, and America. Entrepreneurs alone are obviously not enough to symbolically mark a period that artists have also helped identify and distinguish. Andrew Ducrow, and exceptional circus rider's contributions were essential in creating a formal equestrian repertoire. Philip Astley made his first foray into Paris in 1774. He established himself permanently with his son John (1767-1821) in 1782, by building the first permanent circus in the capital, which he named the "Amphithéâtre Anglois." An Italian adventurer, Antonio Franconi (circa 1738-1836), in turn established himself, after organizing bull fights in Lyon. He founded the first French circus dynasty, and his sons, Laurent (1776-1849) and Henri, also know as Minette (1779-1849), developed a repertoire of equestrian exercises.

1830-1880: The triumph of French horse-riding

The second period, extending from 1830 to 1880, saw the triumph of French horse-riding. Andrew Ducrow died in 1842 and the English circus disappeared with him. The French circus, supported by great entrepreneurs such as Louis Dejean, spread its influence over the whole of Europe. François Baucher was confirmed as the greatest circus rider of the day, and the construction of the Cirque des Champs-Elysées in 1841 was to influence the development of permanent circuses throughout Europe. In a few decades, all the capitals, and numerous cities on the old continent gained sometimes imposing buildings. In France, an entrepreneur such as Théodore Rancy was behind the construction of several dozen wooden circuses and a couple of stone buildings.

In 1859, Jules Léotard from Toulouse, created the Trapeze races, a matrix of the flying trapezes, while Louis Soullier travelled in Asia. Circus riders Pauline Cuzent, Emilie Loisset, and Caroline Loyo triumphed with the charm and excellence of French horse-riding in circus rings in the European capitals, and imposed the image of a romantic and elegant circus, which gradually fell into decline flowing the arrival of the three juxtaposed rings in America.

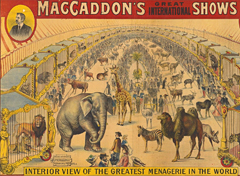

1880-1930: Excess and one-upmanship in feats

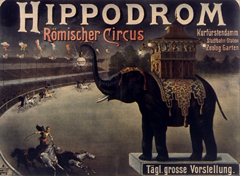

The third period opens with the birth of the first elephant on American turf. The anecdote took on gigantic proportions and heralded major upcoming changes. Two nations shared this decisive interval that stretched from 1880 to 1930: Germany and America were to dominate the circus world by imbuing both the poison of exoticism and the taste for the gigantic, with an equestrian and acrobatic form that was more concerned with academics than seduction. The Hagenbeck brothers supplied the entire planet with wild animals from their Hamburg warehouses, while Phineas Taylor Barnum gave the circus a logic of one-upmanship in feats, and excessive installations. Dozens of giant companies crossed America, soon imitated by their European peers: Krone, Sarrasani, Gleich, and Kludsky in turn set up the three rings that had been the glory of big tops across the Atlantic. The 1929 crash put a sudden end to what some considered to be a golden age, in which exoticism vied with splendid performances and gigantic performance spaces.

- « Before the war, as I remember it » by Jacques Richard.

1930-1990: The pinnacle of the Soviet circus and the arrival of the New circus in France

The last period is a dual one: it began in 1930 when the first class graduated from the Moscow circus arts school, opened in 1927, and ended in 1991 when the Soviet Union broke up. Meanwhile, in the 1970s, a renaissance period began for the circus arts in France, during which the beginnings of a different type of circus, which would last until 2010, took shape.

At the end of the Second World War, the Soviet circus began an extraordinary development process. Likened to the solid vectors of cultural propaganda, acrobats, clowns and animal tamers performed all over the world, brandishing the flag of excellence produced by a rigorous training system. The pinnacle of the Soviet circus was reached in the 1970s, at around the same time as an alternative artistic movement was emerging in the West. The Cirque Bonjour (1971), the Compagnie MaripauleB-Philippe Goudard (1974), Roncalli (1976), the Oz Circus (1978), the Cirque Aligre (1979), the Cirque Barbarie-cirque de femmes (1982), the Puits aux Images (1983), the Cirque Plume (1983), the Cirque du Docteur Paradi (1985), Archaos-cirque de caractère (1986), Zingaro equestrian and musical theatre (1984), the Cirque Baroque (1987), the Cirque Eloize (1993), and the Cirque du Soleil (1984), constituted the avant-garde of a different type of circus, concerned with incorporating meaning and narration, by integrating their feats into a global story. This artistic explosion was supported by the development of schools: from now on, the mysteries of acrobatics could be acquired just like science, or foreign languages, and these training centres would also gradually establish forms and aesthetics.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 tolled the bell on one reign, but France had already come to the fore by promoting the circus arts through an ever-denser network of circus schools. Class levels range from leisure activity to professional training and even advanced degrees, at places like the National Centre for Circus Arts / in Châlons-en-Champagne and the Académie Fratellini. They have been accompanied in this artistic renaissance by the National Circus School of Montreal/ and the Advanced School of Circus Arts/ in Brussels. United in a European federation, these institutions, which not only offer training, but also push the envelope on what circus arts can be, have contributed to defining today’s circus. In 1995, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of the National Centre for Circus Arts / Centre national des arts du cirque in Châlons-en-Champagne, the choreographer Josef Nadj staged Le Cri du caméléon as the seventh graduating class’s gala performance. The show announced the advent of the contemporary circus. Where companies had previously been drawing on irony, nostalgia or contestation, revisiting traditional references and conventions, adherents of the next evolution defined a circus that was in touch with the world, less concerned with circus history and more inclined to challenge its roots. The development of single-discipline performances offered a new lease on life to most of the techniques that had been cannibalized by 19th-century circuses, one that was much more in keeping with their original independence.

The Théâtre du Centaure (1989), Armo- Compagnie Jérôme Thomas (1992), the Arts Sauts (1993), the Colporteurs (1996), the Compagnie XY (2005) and Six Pieds sur Terre (2006), as well as Rasposo (1987), the Cirque Inextrêmiste (1998), the Compagnie du Hanneton (1999), the Compagnie 111-Aurélien Bory (2000), Un Loup pour l’Homme, MPTA-Mathurin Bolze (2001), Les Sept Doigts de la Main (2002), Race Horse Company (2008), the Cirque Le Roux (2013) and others singularize a different relationship to the body, narration and the apparatuses. They focus on the equestrian arts, trapeze, juggling, high wire and acrobatics, or else they stage shape-shifting performances in which the blending of techniques reconnects with the original mosaic. Nowadays, artists experiment, transcend and reclaim a thousand-year-old vocabulary in order to tune it to their unique view of the world and their desire to express its diversity and rough edges.