by Philippe Goudard

Everyone can access the circus arts, as there is no language, culture or age barrier. Whether we are creators, spectators or researchers, the circus show encourages us to develop numerous representations in our minds. By combining with our experiences, our intuitive or acquired knowledge and our sensitive experience, its components enable us to give shape and form to our imagination, and help us to think, create or transmit. And by showing productions that the circus has continued to create for more than 200 years (and its disciplines, for thousands of years), in the most varied domains of the arts, sciences and techniques.

The four families of disciplines are acrobatics, object manipulation, the clown performances and those with animals, as well as talents linked to the architecture of the space, the apparatus, the logistics of permanent or travelling circuses, of travelling, or even the industry of the show and leisure. All this knowledge and all these skills required by the circus arts professions, contain the memory of the individual, of the species and of the social body.

Standing up, cosmic or biological cycles, nomadism and sedentariness, hunting, agriculture and animal breeding, communication, language and social relations: all of these inhabit the ring, guiding thought and the artistic, industrial and scientific creation developed therein. In addition, they haunt the circus show and life, "these remnants of a fabulous era (…), the genealogical certitude that comes from millennia," cherished by Jean Genet (in Le Funambule – 1955).

Between rise and fall

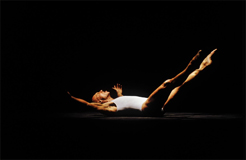

The forms, for which the current circus is the heir and the memory, are a reserve of universal images, signs and situations present in each of us. The memory of the eternal departure, wanderings from the nomadic era, instability, the presence of death, the impermanent and the elsewhere are inscribed in a cycle and a circle. Between the rise and the fall, a vertical axis links the earth of the ring and the sky of the apparatus. Apollo and Dionysus there shared the sublime and the grotesque, harmony and chaos, laughter, fright, the marvellous and the sordid. The transformation into domestic animals of the companions of Ulysses, the nostalgic traveller en route toward his origins, by the magician Circe, to whom the equestrian games ring is dedicated, finds echoes in equestrian theatre and animal tamers, Chimaera and freaks, and animality. Hunting, war, the martial arts, fighting another or oneself, imbalance, risk and feats are all present in acrobatics, juggling, taming and dressage. In the social and entrepreneurial body of the circus, victory and defeat circulate along with power, submission, conquests, barbaric, savage and clown figures, otherness, corporatism and the family.

Desire and effort add an erotic element to the show where the artists use and abuse their bodies in troubling exercises.

Born with the leisure society, the modern circus show now extends into the industry of culture and entertainment. At the risk of Taylorisation, and sometimes supplanting the actual performance, amateur practices, training, and the circus as a therapeutic stimulant or social policy, develop. They are created by an enthusiasm and a fascination nourished by the imaginary fairground world, dreams or fantasies about travelling, the tribe, marginality, freedom and solidarity, as antidotes to a sedentary, normalised, individualist society.

Figuration and abstraction

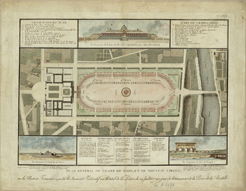

A considerable number of works correspond to the deep fascination exerted by the circus and its shows, across all artistic, scientific and technical domains. The structure has left thousand-year-old traces of the circus ancestors and today, with global and urban changes, it puts into perspective the forms, techniques and staging of the permanent circus, the big top and current shows. As for the pictorial imagination, from the figurative to the abstract, it uses circus images for subjects that go beyond a superficial pretext of its use as a motif. The fundamental characteristics of the circus and the artistic work, i.e., the ring, trajectories and balancing, are brought together in the works of painters, sculptors, photographers, graphic artists and advertisers. The works of Degas, Lautrec, Picasso, Léger, and the Vesque sisters bear witness to this, as does the work of Calder, whose Circus installation prefigures his famous mobiles.

Realism is of little importance in the circus, where figuration secretly masks an abstract art. The laws of ballistics rule trajectories along which the acrobats and juggled items glide, while gravity centres the balance artist's positions as he resists movement. Our wonder lies in the orbits of these objects, animals and bodies, which so fascinate the painter, the physician, the architect, the musician, the choreographer and the doctor.

Media

The circus embodies the values of a society, a culture and an era, as seen in the posters of Jules Cheret, the transformation of the clown Medrano, known as Boum Boum, into a commercial model, adverts using the Chocolat or Fratellini clowns, and Frederick W.Glasier's photographs of the Ringling bros. and Barnum & Bailey combined show artists, as well as numerous current publications.

The vast literary output, of both novels and chronicles, by Gautier, Baudelaire, Goncourt, Apollinaire, Barbey d’Aurevilly, Huysmans, Vallès, Cendrars, Coppée, Prévert, Suarès, Ramuz, Miller, Cocteau, Genet and so many other circus-lovers, demonstrates this passion nourished by their imaginations. Recent works on the 19th century press, on the café-concert, the cabaret and the music hall, on the biographies of stars as well as on the contemporary circus, emphasise the rapport and meeting points between the circus and literature. Circus novels, plays and scenarios inspired by the ring, drafts written for the circus, memoires and biographies, poetry, essays and critical production, all borrow from circus forms and images.

Scenes

From Shakespeare setting out improvisations in his plays for the clowns Kemp and Armin, to Joe Grimaldi; from acrobats and jugglers inspiring Meryerhold in Ariane Mnouchkine's Clowns; from the Lecoq acting classes to the passion for circus of Jean Richard, Silvia Monfort and Pierre Etaix (to whom we owe the first Western European contemporary schools); from the travelling theatre of Firmin Gémier to Jean Vilar's invitation, in Avignon in 1971, to the Cirque Bonjour created by Jean-Baptiste Thierrée and Victoria Chaplin, and right up until the invention of a French style New circus, the need to perform theatre with circus is a permanent one.

As for choreographers, such as Francesca Lattuada, Héla Fattoumi, Joseph Nadj, François Verret, Philippe Decouflé and Howard Richard, among others, they see in acrobats and jugglers a musicality and a multiplying effect on the dimensions of space and an amplifying effect on their imaginary world as much as on their perimeters of influence.

Henri Sauguet, Éric Satie, Nino Rota: these musicians were also inspired by the circus, illustrating and accompanying it, or composing with the very sounds of objects and bodies.

Screens

The fairground origins of the cinema merge with those of the circus, which fed the phantasmagoria of Joseph Plateau's phenakistoscope, as well as films by Georges Méliès. In their wake came the aces of the ring and stage, the cabaret and the music hall, including Sennett, Chaplin and Keaton, who, by transferring their art to the cinema, contributed to the invention of a composition for this new art in movement. Therefore, the circus has, for more than a century, inspired the greatest filmmakers such as Max Linder, David Griffith, Serguei Eisenstein, Federico Fellini, Tod Browning, Cecil B. DeMille, Max Ophuls, Ingmar Bergman and Jacques Tati, Carol Reed, Clint Eastwood, Wim Wenders, Jean-Jacques Beineix and Alex de la Iglésia. Cartoons by Tex Avery and Walt Disney – who drew inspiration from great North-American circus logistics to set up his permanent amusement parks – used rhythms, colours, and images from the circus.

Today, Cirque du Soleil productions use digital methods whose roots perhaps lie in the Notes on the circus that Jonas Mekas directed in Super-8 in 1966.

Sciences

Techniques and sciences were already blending with the movement arts when Tuccaro published his illustrated treaty on acrobatics, or when Muybridge and Marey used photography to shine light on, the physiology of galloping horses or the acrobat's somersault. Since then, the creative imagination of circus artists and researchers has met in numerous technical and scientific domains, such as history, science of the arts, architecture, medicine, the science and techniques of physical and sporting activities, cognitive sciences, humanities and social science, political science, psychology, and communication technologies etc. Numerous research fields produce a base of knowledge that enables better understanding of the appeal of the circus as a show, as a cultural fact and as a mode of human expression.

At the same time, the strangeness of the circus stimulates the curiosity and the imagination of researchers, as a possible experimental model of adaptability. For circus artists build their lives on the insane project of taking a risk on imbalance, to tell of balance in the world. They set us to rights with ourselves and reassure us for an instant through the endlessly recreated feat of survival, offering up their lives for our dreams.

This section of the anthology aims to bear witness to the richness of what these artists offer, both to our imaginations and to those of the greatest creators.