by François Amy de la Bretèque

Something about the very essence of the circus show seems deeply suited to the medium of film: a presentation of pure movement that it is the filmmaker's vocation to record. Reciprocally, shooting a film can, in many respects, be seen as having a circus nature. That was especially true in early film, but something remains of that today. Even conditions for the audience and their behaviour provide similarities. It is therefore unsurprising that there have been numerous encounters between the two arts during the course of their history. Circus characters have gone into film, film people have been inspired by circus characters and famous films have chosen the circus world as a setting. The parallel does not end there. Hidden relations exist between the circus ring and the screen, such as themes and forms found in films that are not explicitly about the circus. This appears particularly in "modern" film.

Early encounters

Journalist and historian Jacques Richard has studied the close relations uniting the circus milieu with that of film in the early days (before 1910). In particular he studied itinerant performers and traced the ancestry of fairground dynasties who showed films under the big top, usually alongside other attractions. He established biographies of many actors and directors from those bygone times, and whose origins and lives are often lost in the haze of history. What we still do not know is whether they really were show business people or whether they invented their own legend. Roméo Bosetti (1879-1948)1, Lucien Bataille (Zigoto) and many others formed the French "burlesque school" and were the forerunners of the American comedians, many of whom also came from the circus. Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin were the most famous of them, but there were also many of Mack Sennett's actors. A whole series of comedy films were directly inspired by circus numbers: comic decapitations, people being run over then resuscitated, thrilling dances, impossible undressing, and sinking, particularly in a pond. From the circus also came the ability to recognise the hero thanks to his "costume and his unusual way of walking, which meant he could be recognised immediately."

To begin with, what these cinematic "views" recorded were simple numbers without narrative development to "package" them. In this way the Frères Lumière recorded an entire series of Foottit and Chocolat numbers. When tapes got longer and developed fro "views" to "films," narration was seen in successive scenes. A sequence of numbers, constituting a circus show, supplied a sort of model for primitive narration. In classic circus films you will often see a blend of these two different forms: "on a loop" with the number filmed in the closed space of the circus ring, or a "sequence" of successive numbers. The circus film kept this heterogeneity even when it became narrative in form.

Setting up stereotypes and the question of a genre

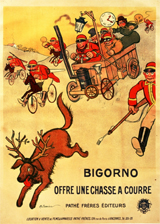

In "classical" cinema from the 1920s to the 1950s, the travelling circus world and the framework of the circus tent show began to stabilise into a repertoire of recurring situations. This process was happening on both sides of the Atlantic in grand show films. Was this the beginning of a genre? We are led to think so by the recurring situations and characters, for example the unhappy clown. Clown Tears (1924) by Victor Sjöstrom depicts a disenchanted and despairing savant who chooses a new life: he follows a circus in France where becomes the incognito clown of the company. The character is played by Lon Chaney, a specialist in transformational roles. This cliché of the sad clown has romantic origins: Victor Hugo, Verdi, and Leoncavallo dealt with him and he has also been illustrated in painting (the Pierrots of Georges Rouault- and the Pierrot grimaçant by Gustave Doré). He had numerous descendants that we can follow to L’Ange bleu, Limelight, Le Clown est roi (Jerry Lewis 1954). Jean Starobinski showed then that he functioned as a metaphor of the artist, who was misunderstood and condemned to entertain crowds. Thus, in film, the clown is not a funny character.

Indeed, the circus show is rarely synonymous with comedy.

The life of travelling people and these nomads who cross the paths of subdued sedentary types, exert a level of fascination based on the opposition between travelling and immobility, perfectly portrayed on film. Classics such as Hector Malot's Sans Famille (adapted several times for film) set the scene. In general, a child or adolescent fascinated by the circus chooses to follow the circus troupe of his own free will or is kidnapped by unscrupulous fairground folk, as seen in Yoyo (1965) by Pierre Étaix and in L’Orphelin du cirque (1925), a four episode film shot while the Ancilotti circus travelled around. Outcasts can join the circus: a prisoner appears in Les Gens du voyage by Jacques Feyder (1937), in which the main character is an animal tamer.

The troupe, the caravans and the big top have the advantage of offering a closed space that encourages all sorts of latent conflicts to arise. Balance is ruined by an external disruptive element: the profane and the neophyte are designated for this part. Drama also frequently turns around a trio: of rivals for the same woman, the heartless rider courted by the acrobat and loved from afar by the clown (L’Ange Bleu portrays a variation on this theme). Another frequent incident is the accident: an acrobat falls and ends up injured, or a lion tamer is seriously injured by a big cat. The Greatest Show on Earth (C.B. DeMille, 1952) et Trapeze (Carol Reed, 1956), filmed respectively in the Barnum & Bailey circus and the Cirque d’Hiver, portrayed these themes.

This type of construction and this type of incident link the circus film to melodrama. It is in fact simply a variant for which only the setting has been changed. But Hollywood requires a happy ending: it's a family genre which keeps everyone happy.

Triumphant during a certain era in American film making, these films are big productions. They form the counterpart to the big budget shows established in the circus world in the United States: Paramount's blockbuster, The Greatest Show on Earth corresponded to the Barnum and Baily circus, know for its extravagance.

The arrival of the neophyte is down to the intervention of the neophyte, whose narrative importance has been emphasized. The archetype was Charlie Chaplin in The Circus (1928), a film in which a man chased by the police takes refuge in a circus to hide, and improvising as an acrobat, gets himself hired. As paradoxical as it may seem – for Charlie Chaplin is always said to have learned his trade at the music hall school, Charlie Chaplin in this film is very clumsy and not at all talented at the profession. In fact, he introduces the spontaneous and unexpected elements of a film character into the well-oiled machinery of the circus act. This film of Chaplin's is therefore, a first, fundamental turning point.

Meeting the avant-gardists

The divergence between the American and European visions of circus in film was obvious at this period in time. In Europe, the subject was above all the occasion for formal experiments. All the avant-gardists from the 1920s and 1930s tried their hand at the genre. One of the main landmarks is the 1925 film, Variétés, by Ewald André Dupont, who was a part of the Kammerspiel2 movement and remained famous for his very mobile camera.

While the young Soviet filmmakers were just appearing, numerous men form the theatre and film looked towards the circus arts and certain schools took it as a model following the Meyerhold the master. Eisenstein made his first tapes to interject them into live performances and his first films (La Grève,1924) are marked by them. The character stereotypes and the grotesque acting come from there. A school such as FEKS (the Fabrique de l'acteur excentrique), wanted to transpose the principles of acting into film, in order to provoke a critical distancing effect. Lev Koulechov made Les Aventures extraordinaires de Mr West au pays des bolcheviks in this way. In France, the first avant-garde movement, also called "French Impressionism,"3 took a similar path and broke away from overly psychological filmmaking.

Entracte by René Clair, with clownish music by Erik Satie, treated it in a satirical style by playing with the extreme mobility of forms. Making forms perform, even without using actors, a bit like in a juggling number, is also what painter Fernand Léger's Ballet mécanique did (also borrowing from dance, as seen in the title). Creating circus without human beings, retaining only movements, diagrams, and in particular circular movements, is an idea that was continued by experimenters such as Calder: Le Grand Cirque Calder 1927 (Jean Painlevé, 1955) offers a miniature circus.

But opposition should not be forced. In the United States too, in the margins of institutional products mentioned above, independent production developed for which the circus theme was important. The most notable representative is Tod Browning. In Freaks and The Unknown (1932 et 1927), the latter took up and subverted narrative clichés from the circus film, less to impose a discourse on "difference" which is too reductive, than to highlight the fantasies and concerns that haunt the average spectator's subconscious: the surrealists were right. The circus encouraged the appearance of the fantastic, or indeed, of horror. Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980) was a perfect example of this.

A nostalgic return to the post-war era

The period that followed the Second World War is often designated as that in which modern film emerged. It is notable that the circus theme made a comeback at this point. In the continuity of neo-realism, Federico Fellini's films (from La Strada to Clowns) are the most obvious examples, as the Italian director makes explicit multiple references, and his drawings also show this. it should be emphasized that the theme runs through his entire oeuvre, and not only his films on the subject.

Another significant film is Jour de fête by Jacques Tati (1947): there is a big top that goes up on the village square, but we don't see the performance. However, the behaviour and "real" life situations are all contaminated by un uprooting which led to talk of burlesque, but is closer to poetry. The same goes for his disciple Pierre Étaix, who was also and even more so, trained in the circus arts, and for whom the entire world was an unreal show: see Tati's Parade and Étaix's Pays de cocagne (1971). The relation between these two directors is explicit. But this reference to circus also appears in early French New Wave films, in scenes from Jules et Jim, Anna Karina and Pierrot le Fou.

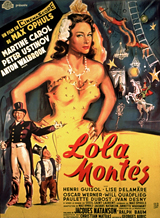

Something of a double premise can be perceived in all these references: a light carefree gaiety conveyed through disguise, and nostalgia for bygone days. The great funereal film in the series is Lola Montès by Max Ophuls (1955), "an avant-garde film on the most conventional of subjects"

New circus et contemporary cinema

Today in the 2010's the circus and circus people have become, moreover, objects of history – or of legend. The film Chocolat by Roschdy Zem (2016), portrays the life of a black clown (played by Omar Sy), mistreated by his partner Foottit, in an allegory of colonial exploitation and race relations, but the presence of James Thierrée in the role of Foottit adds a contemporary circus reference.

The transformations that the circus show has undergone, the appearance of the "new circus" have made films portraying a giant, 1950's Barnum-style circus, old-fashioned. For almost half a century, the circus has been a guarantee for new ways of presenting the body. New German films have taken inspiration from this. For example Alexander Kluge with Artistes in the big top: perplexed (1967) then Wim Wenders, who presented an acrobat, with whom an angel falls in love in pre-reunification Berlin in Wings of desire (1987). Circus became interested into experimental film: French Nikos Papatakis, of Greek origin, made a gay manifesto with Walking a tightrope (1991); in the United States, the king of the underground movement Jonas Mekas made Notes on The Circus (1966), a faux documentary on the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus in which colour and movement played with music.

The circus, a successful dream of a complete show, continued in the 19th century, is, for the cinema, both its opposite (a performing art with a vast space in which the audience are also actors), and one of the closest arts to the form. It has enabled film to create forms and encourage movement, which is its very essence.

1. Roméo Bosetti (1879-1948), was a French actor and director of silent French comedy films. He began his career at the age of 10 in the music hall with drag acts or performing geese. A mime artist and lead acrobat in the equestrian troupe Lécusson in the Barnum & Bailey circus, he quickly went into the burgeoning film industry (1906). We have him to thank notably for the film The epileptic mattress (1906). Jacques Richard Bosetti le créateur , part 3 of the dossier Quand les gens du cirque français inventaient le cirque burlesque, in Le Cirque dans l’Univers N°181 of the 2nd trimester 1996 and « Archives », N°89, Perpignan 2001, Les Acrobates du rire.

2. Kammerspiel (or Kammerspiel film, also known as "chamber drama" was a German theatre and film movement in the 1920s. The name means "chamber acting" and evokes chamber music (Kammermusik).

3. This movement, also called French impressionism, as opposed to German expressionism, was led by the critic and director Louis Delluc, and included filmmakers Germaine Dulac, Marcel L'Herbier, Abel Gance, Jean Epstein and René Clair.