by Philippe Goudard

The global development of the clown's cinematographic figure is driven by the industrial boom of the film industry during the First World War in a North America far away from the battlefield. This period and the following ones, considerably documented, are preceded by a little-known French episode in the history of the first film comedians.

The dematerialised clown

At Keystone Studios in Hollywood, the world's future comedy stars of burlesque cinema began working for Mack Sennett after 1912. Chaplin, Arbuckle, Laurel, Keaton and all the aces of English pantomime or burlesque acrobatics transfer the canvas of vaudeville and clown comedy to the screen. We stick a camera, then we improvise and then we write a story during the editing process: that's what Chaplin mentions in his memoirs. In fact, by recording their shows, they perfect burlesque and acrobatic writing by editing that gives another space-time dimension to the body and the absurd, while contributing to the technical, aesthetic and industrial improvement of cinema. They offer to their art film as a new medium and cinemas as a distribution network. They create new and cinematic clowns for the whole planet. After the purely burlesque beginnings, the clown returns to overindustrialised real life through cinematographic fiction, which opens the doors of discourse and frees his imagination. He gains a social and political dimension around the figure of the tramp, embodied by Chaplin in The Immigrant in 1917 or Modern Times in 1936. Comics from the cinema, the circus or the music hall compete or pass from one to the other like the Marx Brothers, Grock, Yuri Nikulin, Pierre Etaix (in french), Jerry Lewis and today their successors from all cultures.

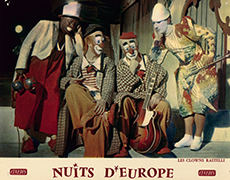

The Clown as a movie theme

Social in Chaplin, metaphysical in Keaton, tragic in Bergman, tender in Etaix and even frightening (It, Tommy Lee Wallace, 1990) the clown becomes a character in films, cartoons, or musicals: Be a clown in The Pirate, (Vincente Minelli, 1948), Phroso in Freaks (Tod Browning, 1931), Frost in La Nuit des forains (Bergman, 1954), Buttons in Sous le plus grand chapiteau du Monde ("The Greatest Show on Earth") (Cecil B.DeMille, 1952).

It is also the central subject: Larmes de clown ("He Who Gets Slapped") (Sjöström, 1924), The Circus (Chaplin, 1928), Grock (Boese, 1931), I Clown (Fellini, 1971) and many short films, inaugurate an impressive filmography from Eisenstein to Hathaway, Walt Disney, Jacques Tati or Alex de la Iglesia. Fictions, some of which are documentaries such as The Greatest Show on Earth or Grock, animation films, documentaries, recordings, form a repertoire as much as an archive, for the history of the clown, the circus and the cinema.

Clowns in French cinema before 1914

by François Amy de la Bretèque

This subject must be addressed from two perspectives. On the one hand, the presence of actors from the world of the circus or more broadly from the music hall is well documented and constitutes one of these "cultural series" that inspired the cinema of the early days. On the other hand, films from the first period – in addition to those that recorded some acts, as Edison did, the Lumière brothers, Alice Guy and others – have staged or perceived clowns' characters as fictional heroes. We can guess that these two dimensions often overlap and that the chain of causalities works both ways. In addition, the porosity between the various performing arts circles at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries requires the historian to be very vigilant.

The presence of circus people on the screen since the origins of the cinema is explained by both institutional and structural reasons. Obviously, in the early years, there was no structured entity made up of film actors: they would only appear during the institutionalisation period, which was in the 1910' s. At first, you have to go and get them wherever they are. There are few or no theatre actors recruited until 1908 and the "Art Series" for a variety of reasons: the tapes are too short, they are deprived of speech, and the target audience in the 1900s does not attend this kind of show. We will therefore naturally move towards the music hall and circus pools, both very fashionable during the Belle Époque.

The French school

Early silent cinema expressed, as Jacques Richard remarks in his Dictionnaire des acteurs du cinéma muet en France (2011) "a verve from circus clowneries that would mark most of the burlesque series of this pre-war period". He has personally highlighted the career path of many of the burlesque actors in the "French school", whether this journey begins on the circus or music hall stage, or whether the future stars on the screen have been trained in acrobatics schools, such as Raymond Frau at the Saulnier gymnasium in Cité Veron. The latter, a member of the Ovaro Bros, "eccentric acrobats", where he is the partner of the clown Gabriel Mansay, began in 1912 at the Italian Cinemas under the name Krikri then in France as Dandy. He shows his "inescapable bourgeois style in the long frock coat of the Auguste", still according to Jacques Richard, which is not unlike the upcoming costume of a certain Charlie Chaplin.

Without reviewing them all, we shall remember some of the most famous examples of these burlesque actors. André Deed, known as Boireau, was not born into the profession, but he went through the café-concert where he performed in an acrobatic pantomime troupe, run by John Price, like his colleague Ernest Bourbon – future Onésime. It is in this troupe that the director Jean Durand comes to discover many of the actors he hires for Gaumont and who become "Les Pouites". Deed also belongs to the Omer filmed by Alice Guy in 1905-1906. The French pantomime troupes were modelled on their English rivals, the most famous of which was Fred Karno's, from which Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel emerged. They even anglicise their names.

Their stars strive to create a character with an easily identifiable silhouette: thus, Boireau "in white or very light suit, cone-shaped top hat or grey bowler hat, heavy cane in hand" inherited from the English slapstick that gave its name to the burlesque genre across the Atlantic. Deed started working in cinema in 1906 for Pathé after a little noticed stint with Georges Méliès, which was probably important for him. He became one of the most inspired of the French burlesques. Today, we salute his surrealist inspiration ahead of his time in Les incohérences de Boireau (1912), which reveals a particular world where a fish is naturally shot in the trees with a rifle and a rabbit is caught alive in the river. It should be noted that Deed is already an international film star. Between 1909 and 1912 he pursued a career in Italy under the name of Cretinetti before returning to France, and at the same time performed on stage in several European countries. Calino – Clément Migé – is an extreme example of the darkness that still surrounds the origin of these burlesque stars. Starting with his biography, which we don't know much about. Jacques Richard assumes that he was trained in the circus but deducts it from his agility and ease with the wild animals, in Calino dompteur par amour (1912), or Onésime, Calino et la panthère (1913), both directed by Jean Durand at Gaumont, which update the theme of the comic tamer. In Calino s’endurcit la figure (1912) he takes up a "theme dear to the circus clowns": The character who serves as a punching ball for several partners without ever falling.

Screen clowns

We have understood this: these actors are not all clowns; they are seldom even fully-fledged clowns as such. But their training is versatile out of necessity. The emerging genre in which they are going to excel pushes them to pick up and adapt for the studio what they have learned on stage or in the ring. They would import certain comic situations into the cinema, or even entrées in the ring without changing anything, such as the spinning board in Dandy mitron (1920). They will gradually transpose and adapt the gestures and clownish expressions that made their success, grimaces, tears, rolling eyes....

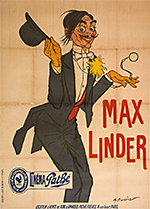

Most often, they create a character based on the Auguste of the stage: extrovert, fearful, scapegoat and whipping boy and they keep part of his costume: narrow jacket, trousers too wide, shoes too tall, the paraphernalia of a bourgeois who became a tramp. But not always and with multiple variations. However, are they clowns in the original sense of the word? We must be careful not to give any doctrinaire answers. The technical constraints of the orthochromatic film impose on them a rather heavy make-up which is also used to help them be recognised, such as Boireau's arched eyebrows. Nothing comparable, however, to the heavy make-up worn in the ring. As cinema becomes more aware of its own resources, they lighten the caricature of their character. Everyone "washes his face with his clown make-up", as Jacques Richard so rightly writes about Raymond Frau. The realism inherent in the cinematographic image, even in a universe as disconnected from reality as the world of burlesque, requires this to be considered. Making their character feel more human is another matter. This will be Max Linder's contribution before Charlie Chaplin. But we can argue, with the risk of being overly simplistic, that they invent the "screen clown" by replacing the circus clown. And one may wonder if, in the long term, there will not be a feedback effect on the performance and appearance of circus clowns.

We must exclude from this analysis the very beginnings: Méliès with Guillaume Tell et le clown (1898), Segundo de Chomon in the character of Une excursion incohérente, stage themselves or represent actors wearing make-up as Augustes. Emile Cohl in Mr Clown chez les lilliputiens (1909) and Winsor Mc Kay in The Rarebit Find (1904), the character of Flip in Little Nemo in Slumberland (film, 1911) do the same in what are the first cartoons in history. We can take a possible idea from this: the clown's make-up emigrates in the animation world....

The clown as a fictional character

Some films from this period have chosen to introduce a clown character into their fiction. It is not as frequent as it was later in the history of cinema. It should be noted that actors from the circus were not necessarily used to portray him. Here are two examples. In Le Clown et le pacha neurasthénique (Georges Monca, 1910), a film by the elitist SCAGL, Prince (Charles Petitdemange), alias the famous Rigadin, is called upon to play the role of the entertainer of a depressed despot – the film seems lost today. However, Prince is by no means a child of the circus: he is a former student of the Conservatory and a former actor of the Entertainment Industry, like Max Linder. He therefore had to perform a character part here. It was his performance, in other words, his "challenge" that made the difference. La Fille du clown by Georges Denola (1911), another SCAGL production, hires Theodore Thalès to play the clown in question. This actor from Marseilles came from the French Pantomimes troupe – he had performed Pauvre Pierrot, the subject of Emile Reynaud's famous praxinoscopic tape, among others in 1890. We are dealing with a drama here. As a fictional character, the clown enters the cinema through the door of artistic series intended for a culturally educated audience, in the tradition of Roi s’amuse by Hugo (1832), Rigoletto by Verdi (1850) and Pagliacci by Leoncavallo, the recent success of opera (1892) almost contemporary with the invention of cinema. The clown as a film character is not intended to provoke laughter.

The clowns of American burlesque cinema

by Christian Rolot and Francis Ramirez

There were many clowns in the movies across the Atlantic too. There were of course all those who came from Europe to try their luck, leaving behind the old world, the small tents, sometimes even the family, exiled without luggage and ready for another life. Among them, Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel of course, but also two future imitators of Charlot, Billy Ritchie (1879-1921) and Billy Reeves (1866-1945), all from Fred Karno's English mime troupe; the Irish clown Paddy McGuire (1884-1923), the French-Spanish clown Marcel Perez (Robinet in the movies) (1911-1914), Clyde Cook (1891-1984), Lupino Lane (1892-1959)... Burlesque cinema was booming at the time, and it was naturally there that most of them took refuge. As for the "native" American comedians, while not all of them came from the circus, many drew their models and the very spirit of their characters from it. Within this somewhat disparate group of people, there are several families: the leading category, in order of importance, is represented by the lonely clowns.

The first one that comes to mind is obviously Charlie Chaplin. When he started in 1914, the comic strength of this frenetic little clown was almost immediately apparent. But soon, his extraordinary ability to mix laughter and tears made him much more than just a clown. The combination of genres was not without danger, however, so he carefully ensured that the pathetic tramp never overtook the mischievous and playful Auguste who, by his antics, knew so well how to instil tension again in the melodramas.

Harry Langdon (1884-1944) will be, for a decade only, the charming little clown, not yet completely out of childhood, mischievous but not mean, to whom we felt like forgiving everything. Between this Auguste and the public, there was only shared tenderness.

In the big baby category, Roscoe Arbuckle (1887-1933), whom everyone called Fatty, also had a disarming smile. Yet he was a cruel baby, whose partners often had to be wary of. An excellent mime, a precise stuntman, he used his formidable weight to conquer the audience and bring joy to the detriment of his comrades, notably Al Saint John (1893-1963) and Buster Keaton (1895-1966) whom Arbuckle capped on the film sets of an undivided authority.

On the other hand, one might be reluctant to classify Buster Keaton as a member of the Auguste family, despite his long shoes and oversized clothes. For an Auguste is a clown, inferior almost in everything if one believes Aristotle, whom the public sometimes affects to love, but whom it is difficult to really respect. However, it is impossible not to estimate Buster. His grace, the purity of his feelings, the power of his ingenuity and his perseverance in adversity often transcend his modesty in heroism. He is the opposite of a buffoon; one of society's loser perhaps, but a sublime dropout. We can only admire.

Faced with Keaton's beauty, the ugliness of a Larry Semon (1889-1928) or a W. C. Fields (William Claude Fields (1879-1946) completed the gap. The first will be a skinny, feverish and agitated Auguste, the second a drunk with a red nose, disillusioned, cynical and all the more convincing as this nose of an Auguste drinker, nature has granted him for life. For them, ambivalence is obvious: sometimes dominated, almost pitiful Augustes, sometimes imperious dominators towards a weaker or more unfortunate person than them1.

Alongside these great soloists, the duets developed in American cinema from the 1920s onwards, according to the formula tried and tested in Europe by the white clown holding authority and knowledge, and his unruly Auguste, who decidedly learnt nothing at all. This formula had the merit of better embodying, by duplicating them, the two sides of the same character, thus making them more readable, more caricatured too, but opening up many dialectical possibilities between good and evil, strength and weakness, knowledge and ignorance…

The most famous tandem was undoubtedly the one Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy formed in 1927. Once again, using their opposite physical characteristics, the roles were distributed in a natural way. As with Doublepatte and Patachon, Harald Madsen (1890-1949), the largest, and Carl Schenström (1881-1942), the slim man, their Danish precursors, the fat man dominated the thin man, at least on the surface. Because here, the contrast is misleading, and nature is at fault. The originality of their style comes from the fact that we are in the presence of two Augustes, one of whom – Hardy, to be precise – persists in believing that he was born a white clown. However, his authority is constantly being violated by Laurel's victorious criticisms. And since it is usually the victim – that makes people laugh – who wins the public's sympathy, the regular defeats of the presumptuous Hardy distribute the comic potential very evenly between the two accomplices, thus creating a happy balance, rarely achieved since.

Abbott and Costello, Bud Abbott (1896-1964) and Lou Costello (1908-1959), whose success was also immense between 1940 and 1945, are far from presenting the same harmony. There is clearly a kill-joy white clown and an Auguste clown on whom all the comic effects depend, Costello being nothing more than Abbott's stooge. Unlike Laurel and Hardy, role switching never happens. The opposition between the tasteless dryness of one and the joyful madness of the other is definitely established and leaves no surprises.

Closer to home, Jerry Lewis (1926-2017) and Dean Martin (1917-1995) appeared in 1946. This time the clown looks like a retarded teenager whose outrageous faces express the deepest stupidity. Jerry Lewis resolutely chose artificiality, where Laurel, his master, on the contrary, cultivated a certain natural quality. This kind of comedy, until then mainly reserved for actors of limited means, is here enhanced by the youthful virtuosity and exceptional inventiveness of the performer2. In front of him, crooner Dean Martin shows himself to be an understanding white clown, sometimes even an accomplice, who is saved from banality only by his charming, beautiful, flowing voice. This new kind of contrast worked for a time, before the couple broke up in 1956 and Jerry Lewis, who was now deprived of his stooge and unable to make his point, turned into a solitary Auguste.

Rarer although even closer to the historical tradition of the circus, which, as we know, originally consisted of clowns who were not artists on an equal footing with the others, but mere auxiliaries in charge of entertaining the audience between noble acts, trios, quartets and more were also born, with troupes containing an abundance of evening Augustes. In the cinema too, the troupes flourished, especially at the beginning of the century, but their existence was only short-lived. The trios were generally luckier, such as the Three Stooges, the Ritz Brothers, but never equalled, far from it, the Marx brothers. Chico, Groucho and Harpo did not come from the circus, but from the musical. Yet Harpo was an inspired Auguste, locked in a world where adults had no access, while Chico and Groucho shared other jobs, more in touch with reality. The miracle for them is that each of them highlighted the other two, in a skilful balance, maintained film after film.

We could not conclude without reminding ourselves, even quickly, that many of these clowns were the ones who, during their careers, wanted to express all that their art owed to the circus. Chaplin of course in The Circus or Limelight, but also Harry Langdon, Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, Dany Kaye, Jerry Lewis and many others. Once again Buster Keaton stands out, who, in a work that is nevertheless abundant, never made the slightest allusion, either directly or indirectly, to the world of circus tents. In the latter part of his life, however, he came three times to Paris to perform at the Medrano circus. That was in 1947, 1952 and 1954. Should this be seen as the need to return to the roots, the late desire to pay tribute to this old Europe that had given so much? No one can really say that. It was, in any case, as the time approached to bow out, an elegant way for perhaps the greatest of them all to make up for it and pay off his debt.

1. Such as Red Skelton (1913-1997), Joe Brown (1892-1973) and Danny Kaye (1913-1987).

2. Between 1990 and 2015, the British comedian Rowan Atkinson (born 1955) would go even further with grimaces held until they culminated in pain.