by Pascal Jacob

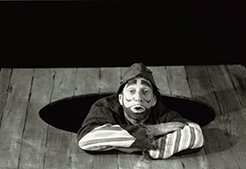

The dust from the boards is well worth the sawdust from the ring for those who choose to be a clown, yesterday and today. Comedians with trestles, roaming from one stage set to the next, clowns take advantage of the setting like others do of the gardine. The performance area is not round, but the stage cage has other assets and can be used as an atypical playing area for a character who has historically come from the theatre, but whose identity has been associated with the circus for 250 years.

Crossroads

A preference for the stage makes it possible to overcome a certain number of constraints, but also forces the clown to deal with some parameters unknown to the circus. Assimilating distance, accepting or circumventing the fourth wall, are vocabulary elements as strong as circularity and envelope, but the essential difference is undoubtedly in a reverse balance of power.

When in the ring, the clown is dominated by the spectators, but when he is on stage, he has a strange ascendancy over his audience. This possible reversal of roles and powers undoubtedly has a significant influence on the choice to be, or not to be, a circus or theatre clown. The fact that the artist prefers one or the other of these territories does not prevent him from performing there on an alternating basis, but it must be noted that from the second half of the 20th century onwards, those who appreciate the boards finally take little or no risk in the ring.

Freeing yourself

The possibility of being a clown without working under a tent is a small revolution that flourished at the dawn of the 1970s. Certainly, some precursors, such as Grock in the 1930s, had already chosen to forge their careers in a circuit of great theatres for which they adapted their playing, but in the wake of the events of the 1968-1978 decade, a generation of new clowns, without denying the codes of the circus, seized this neutral and open space and shaped it with their hands. These young "heirs" draw powerful outlines that help to structure and articulate a multifaceted practice. The body and the verb are founding axes for many artists who rely on the former and neglect the latter. Dimitri Jakob Müller, born in Ascona in 1935, discovered his vocation at Circus Knie where he saw for the first time a clown, the kind Andreff, who made a lasting impression on him for the rest of his life. Since his debut in 1960 at the Schauspielhaus in Zurich, Dimitri has based his comic register on the practice of mime, but it is a register that he has enriched with an in-depth work on space and props, creating a kind of parallel universe at the edge of the theatre of objects. Despite a few incursions into Circus Knie between 1970 and 1979, Dimitri spent almost his entire career on the stages of theatres around the world, including his own, founded in Ascona in 1971.

An artistic destiny similar to the career of the Canadian Sol, whose real name is Marc Favreau, a clown with a sharp sense of humour, sometimes subversive, but always imbued with a form of tenderness for his fellow men. Marc Favreau created his character during a television show where his partner was Louis de Santis, the clown Gobelet. The duo will delight countless young listeners on the afternoons until Sol embraced his solo life and began to conquer another audience from one side of the world to the other. A talkative clown, Marc Favreau relies on a very elaborate silhouette of a "tramp" and bases his comedy on virtuoso verbal constructions, sometimes underpinned by bitter-sweet political reflections. Sol marks the time of a very clear stylistic evolution and formalises a singular writing that allows him to claim with simplicity a new clownish identity. This theatrical vein, brilliantly initiated by Dario Fo and Franca Rame, tends to abolish borders considered by many to be uncrossable between clowns and comedians. Based on powerful texts, very politically involved, the clownish style of play invades the stage with a mixture of lightness and innocence, but with a formidable effectiveness. This tension, where words are assembled in proportion to the violence of reality, is astonishing.

With their respective practices, emblematic figures such as Dimitri, Zouc, Sol or Dario Fo intuitively limit a new territory and prepare the way for all those who will choose to be a clown, especially during the second half of the twentieth century.

Transgressive

Juggler and magician, Yann Frisch began by shaking up the rules of play and spirit, introducing a hint of humour into his vertiginous Baltass, undoubtedly paving the way for his formidable show Le Syndrome de Cassandre, where he explodes the codes of performance for the clown genre. In the strictest and deepest sense of the word, he embodies a contemporary, violent and disruptive tramp, while not lacking a certain tenderness. A clown of unusual strength, sometimes fierce to the point of discomfort for spectators unprepared for such a shock, Yann Frisch dismissed the perception of a character long confined to candour and innocence. This abrupt vision of clowning is a path that Jango Edwards has already largely marked out with devastating energy and a keen sense of systematic and thorough demining of the most settled situations. By making insolence and excess the rules of a role-playing experience where the audience plays its part, Jango Edwards deliciously shatters the codes of theatrical decorum. He spits, eructs, exposes himself, metaphorically and literally, finishing his performance in the middle of a trashed stage. He is at the same time the multiplied incarnation of the Shakespearean histrion, joker and clown, a detonating synthesis that draws its inspiration from the earthiness of his ancestors. Jango Edwards creates his clown with broad strokes, a wild outline that he refines and details in the heat of the stage. Always ready to improvise, he works in the living matter of his canvas, shaping a comic that is more organic than reasoned, always on the edge of the audience's reactions. This energy leaves little room for hesitation and each performance is a bit like a train launched into the night, with a hoped-for destination, but with uncertain twists and turns!

By working on a tight and thin thread, Jango Edwards relies on a very safe craftsmanship to revisit the codes of play borrowed from 16th century Italian actors. He shifts the viewer's perception towards unease and disquiet, a principle of immersion that worries more than it amuses, but which rebalances the forces in the halls transformed into effervescent hot pits where nothing and nobody is safe from the ferocity of the clown. This is a dimension that was touched upon by Carlo and Alberto Colombaïoni in the 1970s and that is now being revisited by Cédric Paga in the sometimes-disturbing guise of Ludor Citrik.

Protesters

The clown is perhaps the contemporary discipline where a form of savagery of the imagination flourishes best. Today, torn, brutal, poetic, violent, tender or abrupt, the clown's figures embody both a powerful counterpoint and a proof of resistance to a certain dehumanisation of the world. It is a complex role to assume as there is still a defiance towards a clownish game that is prone to compromise with evil and the darkness of time remains vivid. Yet, despite this concern, many clowns cast an insightful eye with a sharp look at our little and big failings and develop a hard-hitting perception of the vicissitudes of our societies. Disability, intolerance, human displacement, urban violence and tensions of all kinds are now experienced as living materials to feed writings saturated with a vibrant mixture of anger and love. The clown sketches a shattering portrait of the world while cultivating the idea of an exorcism of his fears through their offbeat representation. Blackening also means suggesting a lull, painting with laughter a glimmer of hope, another possible way to pierce the darkness.

It is a multifaceted approach that spans the entire 20th century and allows very different artists to combine irony with meaning. Raymond Souplex and Jane Sourza, actors experienced in all aspects of theatre, revisited the silhouette of the American tramp in 1958, between a tramp and a vagrant, to make fun of a cleanliness campaign launched by General de Gaulle. About fifteen years later, under the disconcerting guise of Coluche, the formidable actor Michel Colucci elevated this form of derision to a high level, largely rummaging through the certainties of a well-meaning society while confronting it with its contradictions. Coluche tirelessly questions human weaknesses, dismantles community fears, sprinkles salt on collective wounds, but never forgets to apply a touch of humanity in the development of his characters. In South Africa, the satirist Pieter-Dirk Uys uses cross-dressing and humour to politicise his clownish speech, marked by the pain of apartheid. His character of Tannie Evita, always accompanied by a cactus, is a funny and fierce shield and has been part of a humanist lineage regularly embodied by clowns since the 1970s.

Figures and characters

Jos Houben, Ursus and Nadeshkin, the Expirés or the Zimprobables base their comedy on words, but also on remarkable physical mobility. Coming from very different backgrounds, the École internationale de théâtre Jacques Lecocq, the École Nationale de Cirque de Montréal or the Institut National du Music-Hall du Mans, they each master an exceptional vocabulary that allows them to build their own repertoire of entrées. This involvement in the definition of an identity nourished by creation also marks the work of the Okidok duo, Julien Cottereau, Ludor Citrik, but also the work of Arletti, Hélène Ventoura, Jackie Star, Gardi Hutter, Emma la Clowne, Masha Dimitri and Proserpine. These strong personalities embody a female clown, but they also break down barriers in a register long considered to be predominantly male-oriented. Some, like Yann Frisch, clown and magician, prefer a slight distortion of reality, invent strange rituals and play with the borderline between imagination and reason, making it more porous to reinterpret the clown play and energy.

Others, such as Goos Meeuwsen or Anthony and Amélie Venisse, develop characters in a humanistic vein and focus more on tenderness and irony. They design fragile sequences that fit between two acrobatic performances or create shows like the Concierge written and created by Anthony Venisse, a summary of experiences from touring where in all the theatres in the world there is always a concierge, a shadow that has seen everything, known everything, but that we forget as soon as the trunks are closed... These characters, who sometimes resemble ghosts, feed the clowns' imagination and offer them effective platforms for developing silhouettes and sequences. Above all, they allow the clown's fantasy to be anchored in a contemporary reality, weaving beautiful moments of complicity with their spectators. Les Macloma, the trio Les Voilà!, the Licedei, John Gilkey or Mooky Cornish, all play with these joyful tensions between a character and an audience while all sketching a very personal comic.

Resolutely out of the ring, but perhaps not totally clowns either, singular characters emerge in the heart of unexpected spaces like TV series where the classic mechanism of the duo forged on an opposition of characters works with a formidable effectiveness. There are many examples, but the actors who embody the centurion Lucius Vorenus and the legionnaire Titus Pullo in the series Rome, broadcast between 2005 and 2007, are particularly accurate in the elaboration of a subtle "stooge/foil" process that can highlight the respective ranges of two excellent comedians. With them, and many others, the clown vein continues to be exploited and to live, or even vibrate and resonate, in many of its dramatic interstices, be they virtual or real.