Clowns at the theatre

by Béatrice Picon-Vallin

It was in 1903, with Les Acrobates by the Austrian Franz von Schönthan (1849-1913) that Vsevolod Meyerhold first met the circus world and its characters, including an old clown whom he played himself. The circus will represent one of the highlights of the multi-directional research that will be the main focus of the great director at the turn of the decade. It forms the basis of the much larger galaxy of the balagan – a fair hut – a working concept, a theatrical utopia that synthesises the minor forms of European theatrical culture embodied by work on French crowd pullers, the commedia dell'arte, Italian, Russian fair huts, cabaret, variety, the German überbrettl, the pantomime, farce, Burlesque film. All forms considered as the receptacles of the universal memory of a theatrical theatre – the subject of the book published in 1963 by Meyerhold – and as the vital forces necessary for the reconstruction of the theatre of the future on the solid foundations of the grotesque – defined as an art of contrasts – which penetrates to the very heart of phenomena, and whose contemporary scene has become too bookish to remember the form.

"If I were asked what entertainment is needed today for our people, when Russia appears to the world freed from its shackles, I would answer without hesitation: only those that the circus people will be able to give through their art."

Vsevolod Meyerhold, Long live the juggler (Da zdravstvuet zongler), 1917

Everything happens as if circus techniques, where carnival sensibility has taken refuge, were reinvested by a modern art theatre in search of its spectator. The circus nourishes three utopias of the Meyerholdian scene: the utopia of triumphant physicality, the utopia of a well-prepared improvisation theatre and the utopia of a radically different audience.

In 1913, in Paris, where he founded La Pisanelle at Le Châtelet, Meyerhold frequented the Medrano circus with Apollinaire, who also shared with him a passion for the commedia dell'arte. Clowns are for him a privileged reference and are invited to the educational team of his Studio (opened in 1913 in St Petersburg) as Jacomino, Italian acrobat clown and eccentric juggler, then Donato, clown comic, specialist in aerial gymnastics. It is a specific preparation for a new actor that Meyerhold is looking for by using these disciplines. He uses the circus without leaving the theatre space, to revitalise it. Meyerhold even stated in 1924 that it was only in the practice of eccentric clowns that "authentically theatrical methods" could be found, which would nurture new theatrical forms. It was a famous Russian clown, Vitali Lazarenko, who came to play the leader of the devils in Mayakovsky's hell in his staging of Mystère-Bouffe in 1921.

This interest in clowns was then shared by many European artists: Jean Cocteau, Darius Milhaud, Firmin Gémier, Jacques Copeau rushed to Medrano to see the Fratellini, considered as "actors of the ring". Copeau, like Meyerhold, invites clowns to the École du Vieux-Colombier. However, the psychological game is preserved there, and far from the Meyerholdian radicality, it is not a question of renewal, but of a nostalgic addition, despite his intuition that the clown is a "real actor".

The "people's buffoons", as the Russian poet Alexander Blok calls them, are therefore called upon to intervene on stage. Sergei Radlov in Petrograd creates the Popular Comedy where he hires clowns. In Prague from 1927 to 1938, the two clowns-singers Voskovets and Werich performed as a duo at the Théâtre Libéré with immense success.

In the 1960s, Ariane Mnouchkine discovered working with clowns under the direction of Jacques Lecoq, with dazzling results. She shares it with her troupe. In search of a popular theatre, for a popular audience, the troupe dreams of a... popular form and engages in an experimental collective research, without written text as a starting point, which will last for more than six months.

"At first, we intended to do some improvisations by mixing all the characters: Harlequin, clowns, we even wanted to use Bécassine. Little by little we discovered that the clowns were so strong, they were more modern, and they ate everything. We ended up with a show only with clowns."

Ariane Mnouchkine, Les Clowns, Théâtre d'aujourd'hui collection, TV show by L. de Guyencourt, directed by J. Brard, ORTF, 1969, Doc. INA, 2006

There are many difficulties. The Théâtre du Soleil's first collective creation is thus a difficult individual creation for several people: out of more than twenty-five actors, only ten clowns will emerge. The second difficulty concerns the exhausting physical engagement demanded by the characters that the actors generate, the third difficulty relates to the problems posed to female clown performers. The actresses will succeed in composing explosive creatures who remain women, with wild and colourful beauty, and who, through their outrageous acting, denounce the status of women in a male-dominated society.

The show is a milestone. First performed in April 1969 at the Théâtre d'Aubervilliers, then performed outdoors at the Festival d'Avignon and on tour at the Piccolo Teatro in Milan, it was revived in 1970 at the Élysée-Montmartre. The Clowns du Soleil question society and bourgeois stereotypes, but also the condition of the actors themselves.

Les Clowns enabled a demanding and formative research on an unrealistic, non-psychological acting style, and the long preparatory work gave the actors precision and rigour. The actors have gained first-hand experience when it comes to risk and have a better understanding of the childhood world as a whole. But the masks that had tried a timid breakthrough at the Théâtre du Soleil soon took their revenge and ended up chasing clowns and triumphing in L'Âge d'or (1975).

It should be noted that the 1969 show did not feature circus clowns, but theatre clowns, in which women had been able to take on traditionally male roles. It was, a little before its time, a show close to what we will call the New Circus. A show that set the company on the path of the great collective creations of the 1970s. Les Clowns complete one cycle at the Théâtre du Soleil but begin another and the little red noses will reappear from time to time in the troupe's theatrical work, in rehearsal.

The clown in avant-garde theatres in France

par Krizia Bonaudo

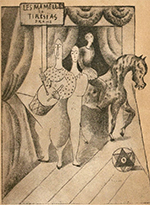

At the beginning of the 20th century, the avant-garde theatres, with Guillaume Apollinaire and André Breton in particular, found in the circus and its characters a physical place and an ideal for formal and performative experimentation. The plays draw on the themes, performance and language structure of the fairground show. The vast reservoir of the circus reinforces the spectacular aspect of the avant-garde project of renewal and challenge to academic rules, of which the clown, through his skits and grimaces, is the ultimate desecrator. A model of the complete artist, actor and banquiste at the same time, he plays a privileged role as spokesman for an experimental message, new expressive techniques and new ways of directing.

The clownish entrées based on tumbles, comic falls and bodily activities, infuse the show with the dynamism, surprise and speed that are typical of the fairground show.

The clown's own body changes the relationship with the audience, encouraging them to cross the line between the stage and the auditorium and to actively participate by following the incursions of the artists juggling and interacting with the audience. The clowns' phoney talk also becomes a language model for avant-garde artists who use puns or a fairground vocabulary to develop an aesthetic that reflects the unconventional and the extraordinary.

Guillaume Apollinaire, André Salmon, Le Marchand d’anchois, 1907, Les Mamelles de Tirésias, 1917; Tristan Tzara, La Première aventure céleste de Monsieur Antipyrine, 1916; Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Le Serin muet, 1919; Pierre Albert-Birot, Le Bondieu, 1920, L’Homme coupé en morceaux, 1920; Marcel Achard, Voulez-vous jouer avec moâ ?, 1920; Roger Vitrac, Le Peintre, 1922; Le Poison, 1922; Louis Aragon, Au pied du mur, 1922/1923 are as many plays based on clown entrées or on the stage presence of the clown.

The clown in the pedagogy of acting in France

par Guy Freixe

Jacques Copeau was one of the first to take an interest in the contribution of clowning to the actor's pedagogy. In January 1916, he enthusiastically discovered the Fratellinis at Medrano. He admires their lazzi, their performance directly in connection with the audience, their rhythmic, precise and inventive gestures. He writes, enthusiastic, in his Notebook: "Here comes the real actor1! ". For Copeau, the clown connects the actor to the vitality of a tradition, namely the commedia dell'arte, based on the spontaneity of improvisation, the credulity of childhood and a completely physical fantasy. Copeau hired the Fratellini in his École du Vieux-Colombier (1921-1924). But their teaching is limited to learning acrobatics. A pedagogy of playing through clownish art has not yet been born. This will have to wait for Jacques Lecoq's contribution. The renewal of the theatre clown owes much to his teaching. In 1962, six years after the creation of his School in Paris, he began work on comedy, which proved to be decisive for the clown's renewal: a clown who would leave the circus arena where he was dying to enter the streets, cabarets and theatre stages. Lecoq has worked on this transformation from a circus clown to a theatre clown, open to new dramatic situations. And he has made clowning an essential dramatic field in the actor's pedagogy, opening it to the burlesque and the absurd.

The pedagogy of the "flop"

In questioning the nature of the relationship between the commedia dell'arte and circus clowns, Lecoq explored exercises to better understand the emergence of laughter: "I was setting up the ring and everyone came in with the only obligation to make us laugh. It was terrible, ridiculous, no one laughed; the clown students were a "flop" in a state of widespread anguish; and, as everyone was going through, the same phenomenon kept occurring. The dejected clown would sit down, ashamed... and that's when we would start laughing at him. The pedagogy was found, namely the pedagogy of the "flop"2. It was not the character the students played that triggered the laughter, but the person alone, laid bare. Lecoq then understood the clown's specificity, far from all the other registers and fields of play where it was a question of playing someone other than yourself. The clown, on the other hand, does not exist outside the actor who plays him. And even so, the less he tries to "play", the less willing he is, the more he lets himself be surprised by his own weaknesses, and the more likely his clown will appear. Because, for Lecoq, we are all clowns, in the sense that we all want to be beautiful, intelligent, strong... while we each have our "pathetic side"3 which, by exposing ourselves, makes people laugh. This discovery of the transformation of personal weakness – physical or psychological – into theatrical strength was of the greatest importance in Lecoq's pedagogy. From then on, the "search for your own clown" became an essential part of his teaching and marked the highlight of the completion of the School's journey. After the process of erasing in front of the outside world, in the search under the neutral mask of a "common poetic background" that gathers and unifies, the student, at the end of the pedagogical journey, in an inverted geometry, must be as simply and deeply himself, and observe the effect he produces on the world, or in other words on the audience. Because the clown only exists from the audience in the first place.

In search of your own clown

To help his clown emerge, Lecoq uses a mask, "the smallest mask in the world" according to his expression, this ball of colour that illuminates the eyes and rounds off the face: the little red nose. This in turn triggers a transformation. When you put it on, it's not just a simple object you put on your face, in fact, it's an event that happens. Suddenly, the intimate takes on a new strength. We feel larger, more available, able to transform our weaknesses into theatrical strength, our failures into triumph. So, by repeatedly missing, being bad, multiplying failures, at a time when he doesn't expect it, the clown surprises himself and us with his virtuosity. For there are within him, hidden, buried – as in each and every one of us – some wonders, and behind his apparent blundering, lie some unsuspected treasures of skill and dexterity.

It is undoubtedly this call to express a deep, secret, unique self that has most seduced in this formula: "the search for your own clown". Training courses have multiplied all over the world, promising everyone, actor or not, to find in a few weeks, even in a few days, "their" clown. Holistic self-discovery program or simple business tactics? It is not always easy to find your way around the various options for working on the clown. Most often the objective is to get the person to lose their inhibitions by allowing them to express their egotism in an unbridled fantasy that gives free rein to their primary impulses. The clown then returns to his original transgressive function, namely, to be a delirious buffoon. Nowadays, he tends to leave the world of entertainment to find his other essential function, his political role, which is to challenge our societies and humanise our lives, by multiplying his presence in places of exclusion and isolation: hospitals, prisons, retirement homes...

In the pedagogy of acting, Jacques Lecoq now has a recognised place in France, in private lessons or in national conservatories and schools of dramatic art, although marginal in relation to the interpretation of texts. The work on the clown, often proposed in the form of a one- or two-week immersion, most often aims to develop in the apprentice actor their capacities of imagination, a self-confidence gained by letting go, strengthening inner belief, the accuracy of the rhythm and openness to the public, because the clown does not play before him, but with him. The encounter with clownish work is always highly anticipated because it stimulates creativity and dynamites the usual frameworks of interpretative play. However, the very individualistic expression provoked by clownish work must not prevent a poetic encounter with a creature that testifies to the mystery of our presence in the world. Without past or future, in a pure present, the clown carries with him the total, irreducible belief in the power of the imagination. This is what the clown initiates, from the perspective of training an actor-creator.

1. Jacques Copeau, Cahier “La Comédie improvisée”, in Registres III: Les Registres du Vieux-Colombier I, texts collected and compiled by Marie-Hélène Dasté and Suzanne Maistre Saint-Denis, Paris, Gallimard, Coll. “Pratique du Théâtre”, 1979, p. 321.

2. Jacques Lecoq (ed.), Le Théâtre du geste, interview with J. Perret, Paris, Bordas, 1987, p. 116.

3. Jacques Lecoq: “The search for your own clown is first and foremost the search for what is ridiculous in you”, in J. Lecoq, J.-G. Carasso and J.-C. Lallias, Le Corps poétique, Arles, Actes Sud-Papiers/ANRAT, 1999, p. 154.