by Jean-Michel Guy

The circus, which is extremely diverse and fragmented, can be seen as a "discontinued continuum" of practices, in other words as an archipelago, to use Gwenola David's description1. To wit, from the Brazilian juggler trying to earn a few cents by dazzling drivers at the traffic lights, to the chronometrically synchronised ensembles of Chinese acrobats with unsurpassable talents. From "social circus" projects working on the reinsertion of wayward youth in many countries, to avant-garde creations that push the circus so far you hesitate to still call it circus. From the small travelling circus crossing the roads of Europe in a caravan to monocycle conventions that regularly bring together amateurs of this highly ecological vehicle, and from the Cirque du Soleil, the flourishing Canadian show industry, to the computer graphics artist who creates sophisticated juggling software, or even virtual circus works.

By adding a thousand dimensions to this flat image, we could compare it to a network, with more or less solid links and an almost infinite number of relations (social function, aesthetic aim, the ontology of the practice, its values, or more prosaically the apparatus, place etc.), between the Brazilian street juggler to the digital circus creator. Moreover, in this specific case, the apparent extreme opposition turns out to be an immediate proximity: on the internet in Brazil, even if you live 5,000 km away from the nearest circus school, you can study the most advanced juggling techniques and prove to the driver in Manaus that a poor juggler has no technical reason to envy an over-trained Chinese juggler.

A network cannot be dismembered. At the most, relatively autonomous zones can be isolated, incorporating a sufficient number of discriminate dimensions to draw pertinent constellations, or islands, to put it simply.

Three circus paradigms

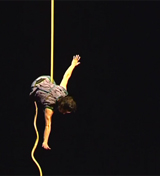

There are three big ensembles that stand out: the classical circus, the contemporary circus and the cultural circus

We will call "classical circus" the first "island-continent" – a genuine Australia, where the notion of classicism refers universally to a simple, ancient norm. Contested in certain parts of the world, elsewhere it is incontestable, as though naturalised. The label "traditional circus," common in Europe (since it was identified in the 1980s in response to the emerging "new circus"), and sometimes asserted against a certain type of modernity, is barely relevant as it sets as "tradition" a very confined (1950s and 1960s) and very "constructed" history of the circus. It also wrongly positions, at the same level, practices which are genuinely traditional – or in any case extremely old and still on-going, such as equestrian acrobatics in Mongolia and a western genre in constant evolution.

The second archipelago shall be called "contemporary circus," – here for example the image of multi-cultural Indonesia comes to mind – which is characterized a minima by a contestation of classicism, or certain of its features. In fact, it cannot be easily defined otherwise, although it tries, but the permanent redrawing of its internal frontiers prevents it from doing so, thereby giving it a perpetually unstable identity, dissatisfied with itself, and which could not be found even outside the principle of lability. This type of circus is described as contemporary for several reasons. Firstly, because the expression "modern circus" (which might be seen as opposing the expression "classical circus"), has a precise meaning for historians: it designates a genre of show, invented in the last quarter of the 18th century in England, by opposition to an unqualified, or "pre-genre" circus. Until Charles Hughes created his Royal Circus in 1782, the word "circus" it is true, only designated a place and the oval shaped space in which chariot races took place in Ancient Rome, in addition of course to demonstrations of various acrobatic skills. The expression "modern circus" applies to that which was invented in Europe between 1786 and 1850, even though the historian Caroline Hodak thinks it more judicious to speak of "equestrian theatre" to describe this new genre, and to reserve the word "circus" for shows which specifically went on beyond this.

The second reason is that the expression "new circus" which came into use in France at the end of the 1980s, is historically dated and no longer corresponds, at least in France, to the extremely open vision that "contemporary circus" artists have of their art. New opposes old: this adjective indicated, in the 1980s, that "another circus" or "other circus" was possible, and implicitly disqualified the current circus – supposedly the one and only – turning into an old-fashioned discipline, "closed to the other and the present." At the time, what was new, was the trend for the theatrical, or more generally, the search for "meaning," which a simple demonstration of talent (knowing how to juggle for example), was not supposed to be able to communicate on its own. At the time, only theatre or narration, even if non-verbal, seemed to have this power. The French "new circus," which seemed so strange to many foreigners, was frequently re-named "circus-theatre" or "theatre of circus," in particular in Scandinavia, or it was occasionally accepted: in Japan, "new circus" is not translated and is pronounced in the French way. Exaggerated importance was probably placed on the "recognition strategy" that French artists, as new circus pioneers, followed in borrowing from the theatre – a legitimate and recognised art form – in the aim of ennobling their non-verbal art form reputed as simply entertaining, and "mute" on world issues.

Meaning was essential, and the passage through the theatre was practically obligatory, as was, by the way, reference and reverence to the "classical" circus, but the quest for recognition by public authorities came late, and was only formulated as such with the arrival of the Socialist Party in power in 1981 (even though, in 1978, at the initiative of President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, the "circus affairs" that had been treated on a case-by-case basis by various cultural affairs ministries including that for agriculture, had become the exclusive domain of the cultural affairs ministry).

The "new circus" was first and foremost a generation of artists that wanted, both politically and artistically, to obtain recognition of the circus as an art (marked by union activism in France), and that finally led to the genre of contemporary circus that overtook them (we will not use the term "creative circus" that a French union chose as a title, for after all, classical circus can also be creative).

If the circus is contemporary, it is not because of its youth or topicality. Just like the 50 year old genre of "contemporary dance" today taught in schools alongside hip-hop and jazz, the adjective describes a genre, or better, an attitude, described rather well by the philosopher Christian Ruby as "being in a permanent state of contestation with your own era. Such a definition authorizes the avant-garde, but is neither reduced to it nor calls on it. It welcomes the "hyper-present" moment of the clown, does not disdain memory and especially, understands that it is dated in advance, which implies a perpetual leap into the unknown for the creators.

1. Gwenola David, Les Arts du cirque. Logiques et enjeux économiques, La Découverte, Paris, 2006.