by Pascal Jacob

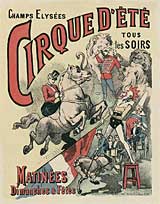

Since its beginnings in 1768, the history of the circus costume has been marked by a series of structuring and founding notions: abandonment, ornamentation and assembly. It is by sticking a feather to his tricorn, between a desire for fantasy and a symbolic gesture, that cavalry officer Philip Astley transforms himself into an entertainer. Thus, symbolically, on an aesthetic and theatrical level, the circus costume is born from the acceptance, interpretation and abandonment of a military uniform. Its identity is based in part on this warlike artifice, and this ardent memory influences the meaning of the representation, at least in its early stages. Powerfully coded, the outfits of 18th century squires and acrobats are characteristic of the era of equestrian theatre, which is the beginnings of the modern circus, and they represent riders and acrobats in a unique, ardent and brutal approach, while also reflecting a romantic flair.

References

By deliberately choosing ostentation and splendour at a low cost, the circus draws the aesthetic boundaries of its territory, both to transcend the initial amazement and to distinguish itself from other spectacular formats. With its references to the clash of armoured suits, assaults and battles, its equestrian vigour inspired by the mud and blood of the battlefields, the circus symbolically resembles a dance of death. Its attachment to this red colour, to the shining glitter and to pure strength makes it much more unique than any other form of complicity. By magnifying his uniform, Philip Astley undoubtedly responded to an economic necessity, but he also had the right intuition: the allure conferred on him by his officer's uniform, the proximity of his exercises with the dynamics of the battle, which were the first terms of an implicit contract with numerous consequences in the 19th century, allowed him to anchor his representation in a familiar and unique context. Not to mention the possibility of using swords or sabres to magnify the feats by manipulating them between two jumps.

This was the right choice: cut for war, loaded with harnesses, the uniform accompanied the soldier without obstructing him. It gives him a spectacular look, in the truest sense of the word, when a battalion marches for glory in a commemoration ceremony under the sun. Finally, it also provides a low-cost way to separate him from the rest of the population, which is his natural audience. Gradually, with its gold or silver underlay, the original dolman smoothly evolved into a fantasy uniform, in accordance with a quest to assimilate codes and symbols from the outside world to feed the imagination of squires, trainers, tamers and acrobats rather than being a straightforward and overly accurate reproduction.

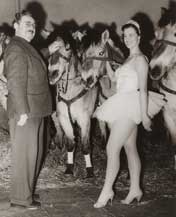

The first outfits are probably based on a simple assembly principle, with elements selected from random discoveries and inspirations. But very quickly, a bundle of thrilling feathers or a scarf with long fringes elegantly draped at the waist were no longer enough to serve as a "costume". To give meaning to the equestrian exercises by developing short scenes and simply characterizing the characters who perform them, the leaders of the troupes will begin to solicit tailors and costume designers to accompany them in this new stage in their history. Freed from the open air, rain and dust, the circus now wants nothing more than to symbolically associate itself with the performance codes of its subconscious rivals, the theatre and the ballet, thus charting the path that it considers most appropriate to win over and retain a new audience.

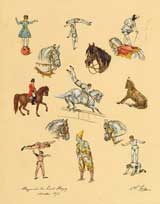

To establish its own visual language, the circus relies on five powerful and synthesised archetypal figures, developed and defined over a little less than a century to date, between 1770 and 1860. The formalisation of all the other clothing conventions involves the aesthetic filter of these five highly structured figures: The Riding School Master, the clown, the horsewoman, the acrobat and the tamer, respectively derived from the bourgeois, the buffoon, the ballerina, the gymnast and the warrior. From the dolman and the garment (1770) to the frock (1830), from the tutu (1832) to the leotard (1859), all future clothing digressions established along the lines of defining a circus costume will be inspired by these five fundamental models, coded and widely reproduced from one side of the world to the other.

The constitution of the circus wardrobe has evolved from a piece shaped in the intimacy of the caravan and adapted to strict contingencies of its handling and appearance to costumes requiring the intervention of several professionals, from the frame maker to the corsetier or from the creaser to the embroiderer. It all starts with a drawing. A sketch on a paper napkin, a watercolour spot with uncertain contours, a flower petal with shades so delicate that they seem painted, such a precise outline that it becomes photographic or a few strong lines, in oil or gouache, brushed on a large piece of cardboard. In this respect, anything is possible: the choice of the stylist guides their hand and ultimately directs the entire aesthetic of their wardrobe. Some people prefer a particular type of support depending on the "personality" of each project. A smooth, fibrous, rough texture. From the drawing, when lines and colours are validated, a work process is developed based on a long chain of skills. The reading of the model is the prelude to any construction principle. This is the first step in the " mystery of the revelation ", this silent transplantation of a vision into a mind that orders, structures, calculates and organises. The financial evaluation will help guide the choice of materials and the possible simplification of some structural difficulties.

Inspirations

Everything, or almost everything, is worth considering in terms of inspiration: animal skins across the torso or around the hips for the tamers when a Roman armour does not suddenly remind us of the ancient arenas... Legends, stories or daily life are also powerful sources of inspiration when it comes to the creation of sometimes very realistic costumes. The Orient, particularly since the conquest of Algeria, has encouraged the development of clothing with shapes and materials drawn from the traditional repertoire of these distant peoples. In fact, the circus is always on the lookout for new things and it enriches its appearance vocabulary both in the light of current events and in the twists and turns of history. The horsewoman's tutu is very simply transferred from the stage to the ring, literally recapturing an original element of the choreographic wardrobe, but sometimes a costume admired in a specific context is only a trigger and leads to a new imaginative world.

From then on, the creative process begins. The choice of materials, crucial because it influences the volumes, the appearance, the specific energy of the costume, is a very special moment that conditions the entire thinking on the meaning of the movement, the light and the characterisation of the character. The sample is followed by the manufacture of the cloths, which includes the construction of a neutral prototype to produce an appropriate volume, the "generosity" of the masses and the solutions to accompany the acrobat's movements. After a few fittings to remove any potential issues that might arise in terms of ease of movement, smooth flow of movement and obstructions in the execution of the technique, the creation of the costume itself begins. Each step is validated by the stylist, with new fittings to appreciate the evolution of the garment as it is enriched and its appearance when it is worn before it is introduced on the ring. A strange phenomenon occurs here, between sharing and transmission, when what was only a simple sketch on a sheet of paper, originating from one or more imaginations, suddenly comes to life, after many months in the making....

Intuitions

Until the 1960s, the circus was one and indivisible. Season after season, its shows attract an audience that comes to see " the circus ", without any other distinction of style or aesthetics than the presence or absence of a cavalry or a flying trapeze routine. After 1968, as the next decade dawned, new companies appeared, created by theatre and dance artists, laying the foundations of an alternative aesthetic wave, multiplying quotations and parodies, revisiting with delight or playfulness the performance codes of the traditional circus. The choice of costumes is a first step in the process of differentiation: some people encourage a shift and develop an aesthetic of the "poor circus" by working with faded colours and worn embroideries. A register that is closer to the simplicity of La Strada than the ostentatious brilliance of the Plus grand chapiteau du monde ("The Greatest Show on Earth"), two reference films that often haunt the memories of the artists who practise another circus. By multiplying the influences, the new circus gradually began to develop a meaningful wardrobe, explicitly linked to the history of each of its shows.

The contribution of stylists and costume designers, who are keen to integrate the entire show into an overall aesthetic concept, is decisive. This "integrity" of the performance, an approach of uniqueness and accuracy granted to the director's or choreographer's purpose, symbolically marks the time of the New Circus.

Wearing a costume that matches a character, or an impeccable, white, grey, tee-shirt or a carefully torn one is a choice. Preferring a pair of shorts, a skirt or a pair of jeans is no exception to this rule of the expressed, decisive desire. By claiming to transform purchased or recycled clothing into circus costumes, the acrobat, the trapeze artist or the balancing act asserts their right to select what makes sense to them when they appear in front of the audience.

Barefoot, effectively connected to the ground, the acrobat revives the idea of a trace, which for a long time was the preserve of trained animals alone. Trampling dust, carpet or floor, he swings between root and cutting. The vegetable metaphor corroborates the fragile appearance of those who prefer to forget references and manage their skin as an evidence and an ornament. At the heart of this quest for spirit and meaning, it is also a question of reinventing costumes as poetic figures, placed in the centre of the ring, and also undoubtedly of hindering the march of time. By wrapping themselves in pieces of clothing from here and now, today's acrobats backdate their exploits and stick as closely as possible to their era. They combine acrobatics, manipulation and balance with their time and they become part of a different relationship with the world.

Transformations

From the 1990s onwards, the circus costume was suddenly stripped down to become the reflection of a conventional wardrobe where jackets, shirts and coats were often chosen for their neutral tones, not forgetting hats and ties... It was from this very banal list that the contemporary wardrobe emerged simply and easily. From now on, girls dress as men and the latter do not hesitate to put on a dress like the one worn by Marcel Vidal Castells in La Femme de Trop or by Jordi Querol for an anthology sequence and a striking effect in #File_Tone, a show created in 2011 by the Subliminati Corporation company.

Throughout his show Où ça? Johann Le Guillerm confronts most traditional disciplines successively, keeping the idea of juxtaposition of heterogeneous forms, confronting rope dancing with juggling, the training of his own body with balance, but he unifies the different aesthetic levels justified by his postures and attitudes by a unique costume, a scenic "bark" in the literal sense of the term, which appears rough and stiff. The material is thick, made from aged leather that conceals a contrasting degree of suppleness and transcends the body of the acrobat, a sculpted bust from which the very essence of the feat springs forth: the artist's naked, vibrating and magnified torso made of muscles. Nudity is a mark of sincerity: beats, pulsations, breath, tensions and stretches are the true signs of the effort.

So, naked, and proud to be naked. Or indifferent, since the contemporary acrobat is able to find reasons to be admired elsewhere than in his physical perfection. Nudity results from a tendency to overestimate the pleasure of doing, a seductive concession to the admiration of the naive who often only detects the pomp and circumstance of it. Naked, all the way from the tip of the hair to the soles of the feet. Naked, to say more than to show. But also, naked to assume their own beauty, to enjoy the reflection of an admiring crowd, fascinated by the perfection of a body as if it had been carved by a sculptor's chisel. A body like the living synthesis of Praxiteles, Michelangelo and Canova, a body offered as a vibrant homage to Stendhal whose syndrome finds in the circus excellent reasons to be expressed when perfection borders on the sublime and captivates everything, reason, heart and feelings. Nudity is a way of reconnecting with the very first moments of innocence, but it is also a strong gesture to assert the freedom of being, a mark of independence that suits the circus well, a world that is both rebellious and discreet, exhibitionist and flashy, tinged with innocence, but also sometimes with a very slight touch of perversity....

Nowadays, the circus costume is no longer really neutral, but it is now an integral part of the artistic creation process, whether acrobatic, clownish or equestrian. In sharp contrast to the traditional costume, the contemporary costume elaborates a tight framework, sometimes even overriding the readability of a somersault in favour of a moving spot that breaks the space and pierces the central part of the ring often abandoned by elements that are too complex or too cumbersome. The demarcation is structured around the idea of contrasts, of lighting a bust with a precious net of gold or silver. Inscriptions that, like marks of civilisation, reflect or bring the costume back to a social dimension or immerse it in other imaginary worlds. It also acts as an architectural feature of the transition. Discovering the back or the torso, the shoulder or the stomach, highlighting or attenuating the shapes, the costume inspires by its active presence, it accompanies all the artist's movements, a confusion of the flesh, marked by a subtle cut or an obvious and deliberate opening. The unveiling is never insignificant and always serves to enhance the value of the body.

The contemporary wardrobe focuses on the use of a single colour but maintains an obvious attachment to noble materials and enjoys the juxtaposition of textures rather than colours. Yokes, visible seams, left as an evocation of a scarification of clothing, sharply sliced fabrics, superposition and muted hues now identify the circus set and involve the same complexity as in the creation of a glitter bolero elsewhere.

Apres a few decades of doubts and experiences, despite a symbolic attachment to traditional values, the affirmation of a true contemporary circus wardrobe now reflects a different aesthetic awareness. Soon perhaps as archetypal as the five founding models, the canvas or leather trousers, often dark in colour, the shirt, generally white, open or carefully buttoned, the black or beige raincoat, the ordinary and regular straps, and the very simple little dress, closer to the light ensemble than the sheath dress, will become emblematic for the next generations of performing acrobats. By playing with a simple effect in terms of material, a juxtaposition of similar shades, sometimes appearing braided with gold, sparkling with trimmings, shaped in linen, cotton, velvet, metal or leather, the contemporary circus costume structures, arranges and orders, simplifies and classifies, suggests and defines. Worn or abandoned by choice, it is a vivid or neutral symbol of the variations of a secular art form that has been constantly reinventing itself for 250 years, from the gestures to the appearance. All the embroidered and sparkling adornments are there solely to magnify this total commitment, which is another way of depicting the human condition.