The circus in children's literature

by Pascal Jacob

« And what is the use of a book, thought Alice, without pictures or conversations ? »

Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 1865

The ancient misunderstanding that associates the circus with childhood undoubtedly draws part of its roots from the abundant literature inspired by a universe as harsh as it can be naive. Using stories full of good feelings and characters sometimes on the verge of caricature, these books describe the circus as an inspiring matrix, but paradoxically, despite their respective graphic qualities, they all resemble each other: they are based on a number of stereotypes, with very simple plots and similar characters from one book to another, but also sometimes from one century to another, and resolutions without surprises. The narrative sequences are very simply divided between a visit to the circus, an easy pretext to "show" all the different aspects of a dramatic performance or opening, a child abduction or a tension within a community.

A repertoire of shapes and colours

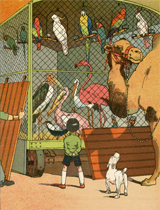

Les Animaux savants by the discreet Baroness B*** born of V...L published in 1816 to celebrate the glory of the Franconis, opens the ball with a small oblong volume enriched with beautiful engravings after the drawings of Jean Démosthène Dugourc (1749-1825). Very quickly, many illustrated works convey a fascination for a colourful show that lends itself well to large compositions capable of competing with the virtuosity of very real representations. Little Alfred’s visit to Wombwell’s Menagerie published in England in 1877 provides a good description of a very real establishment founded in 1810 and active until 1931. The book is a very effective medium, both didactic and promotional, widely distributed in the kingdom's bookshops, but it can also be read as a remarkable testimony to the entertainment of the time. Like the sumptuous Grand Cirque International, a book with a system designed by Lothar Meggendorfer (1847-1925) in 1887, a real book-object that can be displayed on a table or a console. The volume opens in a semi-circle and with its various animated sequences constitutes a remarkable range of equestrian and acrobatic prowess, set in space and in three dimensions.

La Grande Ménagerie, "a great exhibition in six paintings" published in Paris around 1885 by A. Capendu, belongs to the same register, but obviously appeals to another imaginary. These prestigious achievements are both a prelude and a symbol. They mark the time of the circus and contribute to making it popular, but they also freeze it in a series of conventions from which, paradoxically, it will never really be able to free itself. Several books with systems have been written over time in this particular style, such as El Circo by Luis Salgueiro published in 1954 or the highly mastered and readable Humberto, attributed to Voitech Kubasta, designed in the 1960s with reference to the very popular book Circus Humberto by Eduard Bass published in 1941 and translated into many languages, not to mention the very graphic Magique circus tour by Gérard Lo Monaco and Sophie Strady created in 2010.

This forced complicity with a repertoire of obligatory forms and colours nevertheless makes this illustrated literature all the more precious. It also stigmatises, through an obvious evolution of style, the perception of a show whose codes remain intangible. Benjamin Rabier (1864-1939) drew inspiration from it for his album Le Cirque Harry-Koblan published in 1910, but he also created amusing sketches, with biting irony and whose protagonists explore more or less successfully the acrobat and juggler repertoire. One of these drawings in which an elegant woman plays with her muff to make a joyful group of trained dogs jump into it is as much an amused quotation as a precise representation of an original and offbeat circus act.

The triumph of engraving

This principle of illustrations, images designed to punctuate the progression of the story through the text, is part of a long tradition of works embellished and enriched by compositions painted or printed since the second half of the 16th century, where the aim is to embellish works of reduced size with small woodcuts. This counterpoint effect would help to characterise a century of literature for young people from the end of the 19th century onwards and make the countless works regularly published all the more desirable for small readers.

If the great classic of the genre remains Sans famille by Hector Malot published under Hetzel's cartonnage in 1880 with illustrations by Emile Bayard, others like Monsieur Clown by Edouard de Perrodil, illustrated by J. Blass published in 1889, Michael chien de cirque by Jack London (1876-1916), a text published in 1917 and whose editions have followed one another with great success throughout the world, some on large paper and in small editions, others nicely illustrated and printed in thousands of copies like Dumbo created by the novelist Helen Aberson in 1939 with illustrations by Harold Pearl, a story that was destined to be successful worldwide, are also marking the time of the circus. In 1923 James Otis published Toby Tyler or ten weeks with a circus, a beautiful initiatory adventure for a young orphan who ran away with a passing circus and discovered acrobatics and... friendship there!

Since the end of the 19th century, a richly decorated cartonnage, such as the one used in the first edition of Clown Pépé by Edgar Monteil, a large volume illustrated with a hundred drawings by Henri Pille, published in 1891, sometimes adds a spectacular dimension to the work. This is also the case for Pig et Pug by Emile Pech published in 1903, La Petite dompteuse by Armand Dubarry illustrated by E. Noir in 1890, Pâquerette la petite dompteuse by Etienne Jolicler in 1928, Le Cirque et les Forains by Henry Frichet in 1899 or Le Cirque Kutzleb by Norbert Sevestre published in 1925.

Recurring characters

The circus universe also fascinates authors who have a recurring character and it offers them an original context to develop specific stories such as Hugh Lofting when he published Docteur Dolittle’s Circus, in 1924, which was a way to integrate the circus universe into a broader perspective, a bit like an unexpected episode, a festive break in a series of adventures with no real connection with the clowns and the acrobats. This is also the case for Alice écuyère (The Ringmaster’s secret) a heroine adventure created by Caroline Quine, a collective of authors, published in 1953 in the United States and in France in 1959. Harriet Adams is the author of this volume of the adventures of Alice Roy, a young female detective from River City. The English author Enid Blyton also immersed her young protagonists in the world of the circus with Five Go Off in a Caravan published in 1946, which became Le Club des Cinq et les Saltimbanques and Le Club des cinq et le Cirque de l’étoile for the French version in 1965.

This problem of recurring characters can be found in the category of illustrated albums with the adventures of Ernest and Celestine, a series of illustrated books for children published by the Belgian writer and illustrator Gabrielle Vincent between 1981 and 2000. The episode called Ernest et Célestine au cirque was published in 1988.

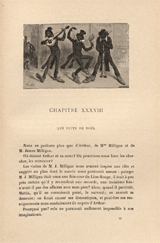

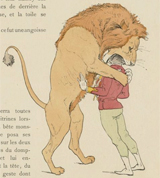

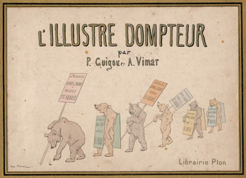

This principle of juxtaposition or integration of images facing or wrapping the text is particularly effective for many albums inspired by a universe that is very rich in surprising, funny or frightening situations. L’Illustre dompteur by Auguste Vimar and Paul Guigou published in 1895 is a good example: full pages and vignettes are perfectly integrated into the narrative and give a very particular character to the album. The quality of Auguste Vimar's drawings is remarkable and he manages, as Benjamin Rabier does in his own way, to give a "personality" to each of the residents of his happy menagerie.

Naive and charming works

One of the graphic commonalities of these naive and charming works is often the regular presence of a double central page: the often-unusual format of these books makes the image all the more impressive! This is the case, for example, for Les Vacances au Cirque, published in 1928 and illustrated by Ribet (Renato Berti, 1884-1939) on a text by Alex Coutet, author of numerous books on various subjects, from Buffalo Bill to Toulouse. The heart of the album is a magnificent illustration of the inside of a small tent where a young horsewoman stands on a piebald horse, a pretty reference to the animals often preferred by travelling troupes, especially in English-speaking countries and more particularly by Irish tinkers. Le Cirque Cirkus by Jeanne Cappe and illustrated by De Santa Rosa, published in 1935, is embellished with magnificent compositions and also features a double central page designed as an explosion of shapes and colours.

From one century to the next, generations of authors have followed one another, but if the literature itself tends to run out of steam, the production of illustrated albums on the other hand is constantly increasing. Le Cirque by Henri Kubnick and Pierre Luc published in 1938, C’est arrivé à Issy-les-Brioches nicely illustrated by André François in 1949, La locomotive Joséphine, a tale by Paul Guth illustrated by Juliette Loubere in 1950, Martine au cirque by Gilbert Delahaye, illustrated by Marcel Marlier, whose heroine was created three years earlier, or Kiri le Clown by Jean Image in 1966, a novelisation of short animation films, are in line with their predecessors. If I Ran the Circus, a strange album full of humour and with a singularly offbeat drawing style created in 1956 by Doctor Seuss suggests another perception of the circus and heralds a clear stylistic evolution, similar to the magnificent album The Circus de Brian Wildsmith published in 1970. Rendez-vous à la Tour Eiffel in 1989 or Petit Fiston in 2014, two albums created by Elzbieta, an illustrator who uses poetic drawing to tell sensitive stories, Peter Spiers’s Circus published in 1992, Eugenio by Marianne Cockenpot and Lorenzo Mattoti in 1998, Jésus Betz by Frédéric Bernard and François Roca in 2001, Circus circus by Madissina in 2005, 21 Éléphants sur le pont de Brooklyn by François Roca and April Jones Prince in 2015, demonstrate the strength of the circus as a source of inspiration, even if nostalgia continues to feed the imagination of creators with a special mention to Sidewalk circus by Paul Fleischman and Kevin Hawkes published in 2004, where acrobats, jugglers and funambulists are not where we expect them! Saltimbanques by Marie Desplechin et Emmanuelle Houdart, published in 2011, is both a subtle learning novel and a sumptuous picture book with both disturbing and engaging charm. Botanic circus by Frédéric Clément, also published in 2011, poeticises the prowess and magnifies improbable characters: Marco, the poppy thrower or Mademoiselle Liseron and her silent morning-glory, are extremely accurate and precise when it comes to writing a funny and offbeat circus score.