The circus in comics

by Pascal Jacob

Considered the first of its kind, established as an original mode of expression born of the imagination of the Swiss illustrator Rodolphe Töpffer, the comic strip album l’Histoire de M. Jabot was published in 1833. This atypical work opens the way to countless creations, a corpus of graphic works where the theme of the circus, a mirror of time, will impose itself as an impressive source of inspiration.

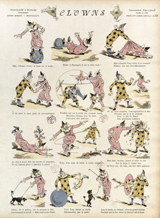

L'Imagerie d'Épinal, for example, produces juxtaposed vignette plates featuring clownish entries, designed in their writing and development as real numbers. It employs many illustrators, some of whom are pioneers in the field of comics.

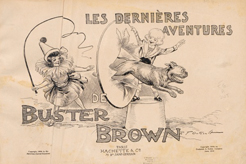

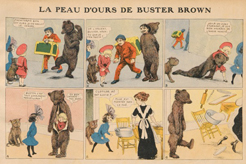

A popular entertainment since the end of the 19th century, the circus naturally enters the storylines, a pretext to feed one or more sequences, an episode or an entire volume in Europe as well as on the other side of the Atlantic. Created in 1902 in the Sunday pages of the New York Herald a name perhaps inspired by the success of the very young vaudeville star Buster Keaton, is a kid who is involved in many different adventures. Included in the 1910 album Les Dernières aventures de Buster Brown, La Peau d’Ours de Buster Brown is an amused illustration of the animal trainers who sometimes perform in public places. Above all, the cover of the album explicitly refers to the world of the circus and includes it among the child's concerns…

The universe of the illustrator Winsor McCay is largely imbued with the baroque fantasies of the American circus of his time. Clowns, acrobats, plumed horses, exotic animals wander through the dreams of the young hero of Little Nemo and give a flamboyant character to pages full of graphic surprises published from 1905 onwards in the Sunday edition of the Herald. The circus is not the literal theme of these sketches, but it does contribute to giving them a familiar tone for all those who frequent the big tops of the New World.

Boxes and Comics

If one of the first exhibition territories of this new medium is the press, the comic strip is also sometimes used for advertising, with Les Jeunes Clowns Fratellini by Gaston Dardaillon, a beautiful album in the Italian style published in 1926 where the famous clowns, at their best, are the stars of funny adventures. The trio was called into question with Paul's death in 1940, but the cartoonist Jacques Faizant nevertheless devoted an album to them, Les Fratellini en vacances, published in 1947.

The end of the Second World War marked a new era for the circus and the big tops that once again criss-crossed Europe's roads motivated the creation of some beautiful albums. André Franquin adds an adventure to those of his heroes Spirou and Fantasio by publishing Les Voleurs du marsupilami in 1954: the wonderful creature created two years earlier was stolen from the zoo that had welcomed it since it was captured in Palombia and sold to Zabaglione circus. There is no doubt that this name is chosen to reflect the success of the Bouglione brothers who perform in both France and Belgium. In 1956, François Craenhals created Les aventures de Pom et Teddy, a rare series that takes place entirely in a circus. This taste for this colourful universe can be expressed in many ways: an episode of Flash Gordon, a hero created by Alex Raymond in 1934, was published as a series in Le Journal de Mickey in the 1970s. The main character, now Guy L'Éclair in French, is a prisoner of a sidereal circus, exhibited in the menagerie and trained like an animal to perform a number. In 1970, René Goscinny and Morris published Western Circus in which they confronted their character, Lucky Luke, with the troupe of a small travelling circus. By offering the character of their circus director the features of the American actor W. C. Field, the authors add an extra touch of humour to an album that is not short of it! Wiser and more naive, Le cirque Bodoni by François Walthéry, Peyo and Roland Goossens, published in 1971, is an opportunity to associate the supernatural powers of little Benoît Brisefer with a universe that appreciates and co-exists with the daily exploit. The 1970s were paradoxically fruitful: the French circus was going through one of its most severe crises, but the albums multiplied, from La caravane de la colère by Paul Cuvelier and Greg in 1973 to Coups de griffes chez Bouglione by Tibet and André-Paul Duchâteau in 1977. In 1973, Le Petit Cirque de Fred, a singular album bursting with strange poetry, reminiscent of Federico Fellini's La Strada nevertheless marked a turning point in the perception and aesthetic translation of a changing circus. Didier Comès' powerful drawing of Silence de Didier Comès in 1980, while continuing to rely on a circus with yesterday's accents, heralds both other rigours and other stylistic freedoms for many albums to come. Published in 1996, L’Enfant penchée by François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters, volume 6 of the series Les Cités obscures, is one of them, mixing photo novel technique and sharp drawing for one of the most original albums of the decade.

Frame or reflection

Sometimes a pretext, often a theme in its own right, the representation of the circus seems to be entering a phase of maturity, tinting the stories with a perfume of austerity, strangeness and above all originality. Les Zingari by Yvan Delporte and René Follet, based on Paul Vialar's novel, initially published in a series in Le Journal de Mickey in 1972 and in Spirou in 1985, or Melmoth by Marc-Renier and Rodolphe in 1990 with its beautifully constructed storyline and subtle colours remain very classic, but others quickly transcend the world of the circus and transform it into a very different language. Fantasy is present in the three volumes of Mangecœur by Mathieu Gallié and Jean-Baptiste Andréae in 1993, the four volumes of Ring circus by David Chauvel and Cyril Pedrosa in 1998 or with Les Farfelingues by Régis Loisel and Pierre Guilmard, published in three volumes between 2001 and 2004. Very structured stories, exploring social themes, mixing tensions and humour, sometimes reflecting a news item or a true story, with few graphic concessions, continue to validate the circus as a powerful source of inspiration. Le cirque aléatoire by Sylvain Ricardet and Christophe Gautier, two volumes published in 2004, Le Sourire du clown by Luc Braunschwig and Laurent Hirn, three volumes published in 2005 as American seasons by Yves Vasseur and Romain Renard or The Ape by Cédric Perez in 2008 based on the Willim Nigh film (1940) with the actor Boris Karloff, are all good symbols of this remarkable diversity in a world still very nostalgic in its outlook.

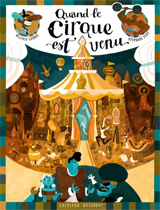

The following decade, which is not yet over, is marked by singular works where Blood circus by Guillaume Clavery and Paul Drouin in 2011, Le cirque – Journal d’un dompteur de chaises, by Iléana Surducan in 2012 respond well to Blacksad by Juan Diaz Canalès and Juanjo Guarnido, a masterful composition where the reader is kept in suspense from the wonderful opening sequence in 2013. The disturbing and magnificent Clown by Louis and Jean Louis Le Hir, three volumes published between 2012 and 2015, the exceptional album La Lumière de Bornéo, a new adventure by Spirou and Fantasio by Frank Pé and Zidrou in 2016 or Quand le cirque est venu by Stéphane Fert and Wilfrid Lupano and Les gueules rouges by Jean-Michel Dupont and Eddy Vaccaro in 2017 magnify with a surprising density of graphic resources a world whose soul and flesh never cease to suggest new deep and sensitive visual asperities.