Landmarks and reflections

From the end of the 19th century to the first decade of the 21st century

by Marjorie Micucci

Why do artists take up the circus as a motif? How do they use the circus as a motif and pictorial space? What has attracted, seduced and fascinated artists (from painters to sculptors; from photographers to video makers and performers) from the second half of the 19th century to the beginning of the 21st century? Is it the – codified – central figures? Or the décors, identified and defined in a new and unique timelessness? Or is it the circus spaces (from the closed circle of the ring to the popular and heteroclite parade whose origins lie in the military parade)?

There have also been phases in which the motif was abandoned, or has seen a lack of interest – in the 1940s, as well as from 1950 to 1970, with of course, nuances that shall be specified. There has been, on the artists' part, empathy and identification, leading Jean Starobinski to critical analyses of social and aesthetic representation in the wonderful essay entitled Portrait de l’artiste en saltimbanque (Éditions Skira, Geneva, 1970, republished in 2004 by Éditions Gallimard, in the "art et artistes" collection). It is also a support for one of the rare ambitious French exhibitions consecrated to the relationship between the circus world and the artistic universe, "La Grande Parade, portrait de l’artiste en clown" (The grand parade, portrait of the artist as a clown), at the Grand Palais from March to June 2004, commissioned by Jean Clair, among others. We can also cite another exhibition organized, the same year, by the La Chartreuse museum in Douai, "Au cirque: le peintre et le saltimbanque" (at the circus" the painter and the acrobat), commissioned by head curator Françoise Baligand.

The circus reflected in the mirror of the avant-garde and of artistic experimentation

So from its creation (in 1768 near London in England), through its extension and growing popularity (in France in the mid-19th century), what has the circus "given" to artists, and to which artists? In a realistic, allegorical and symbolic approach. And what do the artists "do" with or at the circus? What do they do with the principal protagonists and the recurring stylistic or choreographic figures? Those who play in space with the oxymoron of balance and imbalance (dizzyingly), and with lightness and gravity, with stillness and movement, with joy and sadness, with appearance and disappearance? What do these artists do in, and with, their creative gestures and their representations in their mediums? From a brief overview, it would seem that this circus universe met the most innovative and experimental artistic movements in each period of recent art history: from romanticism which, through the expression of a new sensibility, broke with classic representation, to the modernity of the avant-garde in the late 19th century and early 20th century, up until the contemporary era and it genre issues. And that could possibly be a working hypothesis, to build a link, through certain works, between circus figures and gender studies.

The circus and its figures could be this marginal place (meaning a place that is not coded), from which society (modern, western) dreams, observes itself, worries, dresses up, breaks down and performs, again, an act that is both modern and contemporary (rather that post-modern), in deconstructing social, ideological, sexual and cultural norms. The circus world thereby enables artists to both construct and fragment portraits and self-portraits in a mise-en-abyme and in a reproduction of the complex game of norms that is seen in a mirror or in positive/negative.

The circus and its actors: new spaces for modern art

From 1900 to 1920, Pablo Picasso, assiduously frequented the famous Parisian Medrano circus, set up on the boulevard de Rochechouart, and represented harlequins [Harlequin, 1917, Picasso Museum, Barcelona; Portrait of an adolescent as Pierrot, 1922, Picasso Museum, Paris; Paul as a Harlequin, 1924, Picasso Museum, Paris], acrobats [Acrobat family with monkey, 1905, Göteborg Konstmuseum; The Acrobat, 1930, Picasso Museum, Paris], jugglers and circus riders (note the important stage curtain that he created in 1917 for the Parade ballet by Erik Satie, performed by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes at the Théâtre du Châtelet [Stage curtain for the ballet Parade, 1917, national museum of modern art, Pompidou centre, Paris]. However, Picasso is not to be our main thread. Instead, we will look at the American painter Edward hopper (1882-1967), with this painting, Soir Bleu (1914) [Whitney Museum of American Art, New York], a nostalgic memory of his time spent in Paris, and whose central, front-facing figure is that of the white clown. This figure seems to us to be a bridge between modern paintings from the early 20th century and the corrosive, playful, ironic, disillusioned representations. It even seems to take a grotesque opposing view to some contemporary artists such as: Cindy Sherman1, Bruce Nauman2, Ugo Rondinone3 and perhaps, the closest to Hopper's white figure-landscape, the American artist Roni Horn with her series of drawings and photographs Cabinet of (2001) [Hauser & Wirth Gallery, New York-London-Zürich].

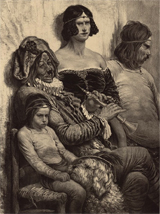

In a sort of shared ancestry, we could, in fact, begin this visual journey by recalling the full length portrait, in the foreground, of Gilles, in the Jean-Antoine Watteau painting, Pierrot, dit autrefois Gilles (circa 1718-1719) [The Louvre museum, Paris]. This character from the commedia dell’arte became a set, melancholic figure, set apart from life and society. Gilles by Watteau was one of the sources of Hopper's sad, immobile clown. The American painter, who made several visits to Paris between 1906 and 1907, lived the Parisian lifestyle of the era. He went to the theatre and other popular places, where he drew portraits of society. He assimilated Courbet's lesson on pictorial realism and that of Degas in the choice of motif, which was to be this Parisian life that fascinated him with its parties, Bohemians, novelties, distractions and characters of modern life. In this panorama of pleasures, there was the circus, which artists, writers and poets loved. In Soir bleu, which he painted in 1914 back in the United States, Hopper unfolded Parisian society in a line oscillating between realism and symbolism. The artist was present, as was the military man, the prostitute, the pimp and a bourgeois couple, slightly alarmed by all these people from different world gathered together in the café.

The artist no longer spoke with the powerful, sovereigns and prelates who commissioned works; he was in his workshop, where he had left painting, or the portrait of history behind. He painted himself and saw himself as the clown he had met in those places of entertainment provided by modern 19th century society. Hopper was established in this "tradition of Baudelaire, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Georges Rouault" and identified the artist with "marginal, acrobats and prostitutes" (in Didier Ottinger, Le réalisme transcendantal d’Edward Hopper, catalogue for the Hopper exhibition, Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 2012).

So the circus really was a "space" in modern life. Artists, poets and novelists seized it, with forms and physical languages that the latter liberated, unfurled and unmasked. They seized hold of the protagonists, both in the ring and in the stalls: the marginals but also the anonymous audience who appeared then like a new "motif" – the modern spectator – and this democratic crowd that emerged, at the heart of a bourgeoning entertainment society.

The fruitful marriage between circus forms and modern art

From the beginnings of the circus, in particular in France where the first temporary establishments opened dedicated to equestrian games and juggling, flying and acrobatic skills (the Manège Anglais at 16 rue du Faubourg-du-Temple on July 5th 1782, replaced on October 16th 1783 by the Amphithéâtre Anglois des Sieurs Astley père et fils), then in April 1807 (the Théâtre Cirque Olympique de Franconi on the rue du Mont-Thabor), a concomitance can be seen between the appearance and the rapid development of these new places and show forms, along with a romantic sensibility that was then blooming. This concomitance grew stronger under the Second Empire. The second half of the 19th century saw the construction of a certain number of permanent buildings: the cirque d’Été (known as the Cirque de l’Impératrice until the fall of the Empire), on the Champs-Élysées in 1841; the cirque d’Hiver (originally named Cirque Napoléon) in December 1852, on the boulevard des Filles-du-Calvaire and the cirque Molier (amateur circus), in 1880 on the rue de Benouville. Later came the Nouveau Cirque, on the rue Saint-Honoré, in February 1886. In the first decades of the 19th century, the circus became established, and distinguished itself.

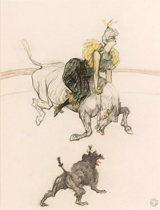

Thus in 1868 with his Clown at the circus (Kröller-Müller museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands), Pierre-Auguste Renoir took hold of this character that we have taken as a leitmotif. He is in the centre of the circus ring, at eye level with the spectators, this new type of audience, that the painter also portrays. We could say that the painting and the motif are "planted." In 1901-1902, Renoir portrayed a White Pierrot [Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit], full length in his white costume, taking up the entire canvas. One can recognise how the motif, and the impressionist representation of this now familiar character, are constituted. Meanwhile, the circus had truly become a favourite theme for artists. In 1879, Renoir represented Acrobats at the cirque Fernando (Francisca and Angelina Wartenberg) [Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago]. The cirque Fernando, built in 1975 on the boulevard de Rochechouart, welcomed this new audience of bourgeois, of artists and the working class. Toulouse-Lautrec was a regular, fascinated by the clown, acrobat and circus rider acts. He found new inspiration for characters, attitudes, line and colour work here: Equestrienne (at the cirque Fernando) (1887-1888) [Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago]. But Toulouse-Lautrec was also haunted by the clown and the clowness: The Clowness Cha-U-Kao (1895) [Orsay museum, Paris]. This remarkable character, who was magnificently raw, lonely, and despairing, was close to the figures from the Moulin-Rouge.

In 1897, the cirque Fernando became the cirque Medrano. A legendary place was born, "a veritable kingdom of modern art." Art and the circus were open to fruitful marriages. Marriages that united the avant-garde and entertainment in modern life, against a backdrop which still included the presence of marginals, travesty, endless possibilities, the incredible, illusion and drama. The circus and its ring became a landscape for artistic modernity, and varied in formal experiments in Pointillism, Divisionism, Post-impressionism, Nabi, Cubism and Fauvism… It was Edgar Degas (Miss La La at the cirque Fernando, 1879 [National Gallery, London]), Georges Seurat with The Circus, 1891 [Orsay museum, Paris] and its twirling circus rider, Pierre Bonnard and his Parade (or Fairground), 1892, [private collection], Fernand who continually explored and worked on this theme until the end of his life in 1955 (The Cirque Medrano, 1918 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris]; The Acrobats in grey, 1942-44 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris]; The Acrobat and his partner, 1948 [Tate Britain, London] ; The Grand Parade, 1954 [The Salomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York]), Pablo Picasso (we have already emphasized the importance of his work on this theme).

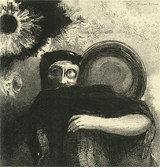

Georges Rouault also took a Christlike circus universe as a metaphor for the suffering human condition (Cirque (The Parade), 1905 [The Ville de Paris modern art museum, Paris]; Pierrot on pink and green background, 1932 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris]; Hollow dream, 1946 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris]); Marc Chagall whose circus figures created a symbiosis between the private imagination and the political concerns of the artist [The Acrobat, 1930 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris] ; The blue circus, 1950 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris] ; Circus on a black background, 1967 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris], Alexander Calder who, during his Paris years, from 1926 to 1933, frequently attended the cirque Medrano and created his fine sculptures from metal wire and in particular, his astonishing miniature mobile (Cirque Calder, 1926-1931 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris]), Raoul Dufy (Acrobats on a circus horse, 1934 [National museum of modern art, Georges Pompidou centre Paris], and in particular Jean Dufy, his brother, a major circus amateur and connoisseur, who from the 1920s to the 1950s, produced and accumulated numerous paintings and watercolours reproducing the colourful, dreamy fantasy of the circus space (The Circus, 1927 [private collection]; The circus rider, 1928 [private collection]; Tightrope walker with umbrella, 1937-1939 [private collection]; Clowns musicians, a recurrent theme until 1958 [private collection]).

The ambivalent return of the clown figure to contemporary art

Modernity, or modernities in the plural, summarize the multiple art forms that the circus motif knew and enabled during this period. Edward Hopper's white clown, which the artist identified with, dissolved in the tragedies of the century. The circus left the artistic scene in the 1960s and 70s. A contemporary moment… It was once again through the figure of the clown, that certain artists today, have rediscovered this circus figure. They have done so via a different filiation to Didier Ottinger, in his article Le Cirque de la cruauté. A portrait of the contemporary clown in Sisyphus (in the catalogue La Grande Parade, idem, p. 35) recalls not those of Gilles and the sad pierrots, but those of the "Hanlon-Lee, six brothers of Irish origin, who with resounding slaps and erratic somersaults, revolutionized the clown art, rendering pantomime and its art of silence obsolete, almost instantly."

And because, once again, this polysemic figure enables identity and stereotype to be questioned, this "contemporary clown" directed by American artists such as Bruce Nauman (Torture of clowns (dark and windy night with laughter) 1987 [Barbara Balkin Cottle and Robert Cottle collection]) and Paul McCarthy (Painter, 1995 [Fine Arts museum, Ottawa Canada,]) in their photographs, videos, installations and performances from the late 1960s and the 1970s and 1980s, served as a vector to contest the modernist model in its conceptual and minimalist format, as established on the arts scene.

This vector was once again an "overturning of values." It was a type of expressive realism that used the grotesque, exhibitionist sexuality, the show society and mass consumerism.

This questioning of identity can bee seen in the work of Cindy Sherman in, among others, a photographic series in the early 2000s (Untitled n°411, 2003 [Metro Picture, New York]) where continuing to work on the image of self and travesty, she creates a self-portrait as a clown. A clown which, beneath a heavy mask loaded with colour and grimacing, carries the sadness and melancholy ofthe clown in Blue evening. This landscape of moving and androgynous identities unrolls with the Cabinet of and Clowndoubt (2001) series by artist Roni Horn. Photographic portraits are cut up and then recomposed, making the image blurred of course, and apparently illegible as well, but perfectly sensitive to a variation of expressions. Doubt and worry are contemporary. From Watteau's Gilles to Hopper's sad clown and to Nauman's grotesque one, Horn removes and undoes elements in order to recompose an ambivalent landscape.

The relations of circus forms with art forms are probably always positioned in this style of inversion and experiences that are both formal and sensitive. Today, contemporary art is more and more committed to forms of performance, and to new performance protocols following the historic era of the 1960s and 1970s. Future writing will probably stem from other forms of concomitance.

The art of the line

by Pascal Jacob

In the West, the Roman era clearly revealed the symbolic appropriation of the acrobat's body, which figured prominently in sacred statuary. Sculpted on many modillions, it symbolised the ultimate step in spiritualization, with the torso and face raised towards the sky.

One of the most famous representations is in the Aulnay church in Charente-Maritime, where the nudity of the acrobat stigmatises his fragility, reinforcing the impression of an effort made to acquire the inner purity needed to accomplish his reversal – in other words the passage form the pagan state to the Christian one. In Loizé, a small commune in Deux-Sèvres, the church gate houses a fine acrobat, supported and protected by a bearded partner – the representation of a sage, obviously – but also a troubling evocation of a secular gesture that aims to parry an eventual fall.

Symbols of progress, rebirth and transition, or, paradoxically, figures suggestive of a demonic character, these silhouettes crafted in stone, tufa, marble or limestone, reflect all the fascination felt by mere mortals for everything that was strange and supernatural. The flexibility linked to the figure of inversion haunted every artistic period, and reflects this propensity for mixing body and soul in a symbolic representation of mystical distortion and elevation.

Funerary art

The Xian pits form a strange domain preserved at the heart of China where, since the 3rd century B.C., an immense army lies, crafted by hundreds of scrupulous sculptors, who succeeded in giving these soldiers imperceptible details that enabled them to be differentiated, and gave them an extraordinary lifelike touch. Recent new digs there revealed – alongside the infantry and the cavalrymen – the presence of a small population of acrobats, dancers and musicians. These sculpted bodies, caught in an acrobatic movement or posture, possess the same significance as the fragile terracotta statuettes buried in the Han tombs. Destined to be substitutes for the corpses of the deceased's entourage, traditionally immolated as a tribute, these delicately crafted shapes embody the pleasures of existence and symbolically accompany the deceased in the afterlife to continue to serve and entertain him. This substitution effect, a phenomenal progress in the history of cults and rites, generated a related and extraordinary blossoming of works of arts. These objects, which are funerary pieces, would gradually acquire art status and were established as an artistic reflection of successive eras. Etruscan and Egyptian contortionists, and Roman and Chinese acrobats were among the finely carved, or barely sketched figures, which were the first landmarks in the history of acrobatic representation. This intense artistic adventure was tinged with a hint of magic and a lot of power.

Beyond the lines

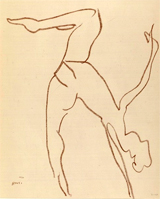

When Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Henri Matisse (1869-1954) in turn synthesized the powerful, sinuous acrobatic body into a line, they used simplicity, beyond the purity of the line, to convey movement and distortion in the space of the representation. Set soberly against a neutral background, their acrobats filled the surface of the canvas, almost colliding with its limits, and they describe, in a long, mastered curve, how physical flexibility matches artistic research. Acrobatics is the cement of the circus and its practice matches that of drawing for the painter or sculptor. In terms of language, each movement and posture is similar to a fragment of the alphabet, indispensable when writing a phrase or a sequence.

Picasso and Matisse continued to create various representations of this fabulous, mystical manipulation of the acrobat's body, up to the working drawing, and an endlessly stretching line, somewhere between a trace and a living memory of all the flights, of all the figures who have imbued the history of a discipline transcended, in terms of an ancient practice, into an intuitive art form steeped in sacred references. If the most ancient traces are a matter of palaeontology, several ancient cultures have valorised inversion and distortion to illustrate rebirth and transition, passage and transfiguration, sliding from the shadow into the light. The body here is both image and vector: it enables above all the efficient signifying of the necessary duality between the world of the dead, and that of the living.

Pablo Picasso's acrobats are often at rest, freed from gravity and traced with a sure and admirative hand, showing the fascination for a marginal world that has never ceased to cross a protean work. The figures of the tumbler, the funambulist, the juggler and the clown are questioned and transcended by Jean Starobinski in Portrait of the artist as an acrobat, Les Odes Funambulesques by Théodore de Banville and The Tightrope Walker de Jean Genet, literary and poetic counterpoints to the artistic creations of their contemporaries.

Descendants

Like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault (1871-1958), Raoul Dufy (1877-1953) and his brother Jean (1888-1964), Fernand Léger (1881-1955), Marc Chagall (1887-1985), Otto Dix (1891-1969), André Derain (1880-1954), Marcel Vertès (1895-1961), Kees Van Dongen (1877-1968), and Oskar Kokoshka (1886-1980), many others have loved the circus, its trapeze artists, circus riders and clowns. They have woven their pictorial vocabulary of powerful bodies, inscribed on paper or canvas like landmarks in memory to convey a flamboyant repertoire of pure, stylised or abstract forms. Before them, Victor Adam and Carle Vernet appreciated the grace and elegance of male and female circus riders, producing canvasses and illustrations in multiple reflections of the spectacular horse riding of the era.

Gustave Doré (1832-1883), the painter, illustrator and sculptor, also explored the theme of acrobats, in particular in his brilliant composition L’enfant blessé , sketched in 1853 and taken up again in 1873 and 1874 with subtle variations as seen in the versions kept at the Roger-Quilliot art museum in Clermont-Ferrand and at the Denver Art Museum. He portrays the distress of a marginal world when faced with a dark destiny, adding strong symbols to his canvas, such as cards and owls, but he also made it a work with a sacred character by suggesting a pious gypsy, using a diagonal structure to create both depth and dynamism. In 1870, he painted a striking self portrait in which he appears as a pierrot, an ambivalent character announcing, in a troubling synthesis, the victimised clown figure with the pallid, disconcerting mask.

Another view

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) and Jean-Louis Forain (1852-1931), as well as Henri Gabriel Ibels (1867-1936), one of the early Nabis, Charles Dufresne (1876-1938), and Edmond Heuzé (1884-1967), who created innumerable works on the Fratellinis and Joseph B. Faverot (1862-1946) – a pupil of the painter and sculptor Jean-Léon Gerome – author of the impressive canvas that decorated the Cirque Medrano booking office, have appreciated the power of the body in motion in Parisian circus rings. They integrated them into numerous compositions, thereby constituting a very rich visual repertoire for understanding the shows of the era. The chisels of Bernard Naudin (1876-1946), Edgar Chahine (1874-1945) and Auguste Brouet (1872-1941) have engraved numerous acrobats, in particular to illustrate Le Bachelier by Jules Vallès (1879), les Fêtes Foraines by Gabriel Mourey in the luxury edition (1927) and the Les Frères Zemganno by Edmond de Goncourt (1879).

The acrobat's body, the powerful horses, and the flexibility of the animals exert endless fascination over artists, whether painters, sculptors, photographers or musicians. The Fantastic Toyshop by Gioacchino Rossini and Parade by Erik Satie correspond to Lulu by Frank Wedekind and Alban Berg: whether orchestral suite or opera, these works involve acrobatic figures and combine the charm and energy that can characterise the dynamism of balance artists and clowns.

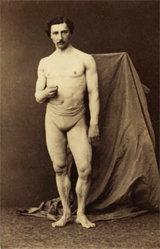

Invented in the first decades of the 19th century, photography, literally a "drawing with light" accompanied the transformations of time and helped set a good number of the most notable inventions. Without becoming a substitute for painting entirely, photography nevertheless accounted for a powerful evocation of men, landscapes and places: the circus very soon became an interesting pictorial and commercial theme. The Bibliothèque nationale de France has kept, in particular, a series of portraits of Jules Léotard, who created the Trapeze Races in 1859, as both artistic and historical evidence that is as much advertising document as artistic gesture. Technical developments enable photographers to seize movement and to still action with precision, providing a field of endless exploration. From the first years of the 20th century, clowns acrobats and circus riders as well as big tops, life scenes, parades and camps would all be embodied in the lenses of numerous photographers, fascinated by the mix of strangeness and brilliance that distinguished this universe.

August Sander (1876-1964) included circus men and women, and artists and technicians in his famous People of the 20th Century created in 1924. Otto Umbehr (1902-1980), a photojournalist and artist captured the clown Grock in a series of striking portraits, while Izis (1911-1980), Pierre Jahan (1909-2003) and Brassaï (1899-1984) were attached to the behind the scenes poetry, tracing in black and white, moving lines of strength in a world already weakened by the developments made in modern society following the Second World War. Paul de Cordon, François Tuefferd (1912-1996), Robert Doisneau (1912-1994), Philippe Cibille, Gilles Henri Polge and Christophe Raynaud de Lage, contemporaries, were the heirs to and the continuation of the French School, supporters of humanist photography, careful to account for the realities of a world in progress, and to poetise its most astonishing moments.

Snapshots

In the United States, Frederick Glasier (1866-1950) immortalized the daily life of the great travelling circuses, in particular the Sparks Circus and Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey. He paved the way for a generation of photographers who would make the circus one of their occasional or recurring themes. Jill Freedman (1940 -), who mainly followed the Clyde Beatty and Cole Bros. Circus and its elephant herd, which gave rise to magnificent images, Paul Strand (1890-1976), Robert Frank (1924-), Bruce Davidson (1933-) and Diane Arbus (1923-1971), were all interested in a marginal community in the American way of life and produced magnificent portraits whose singular beauty arose from the use of black and white. In her series based on the people of India and Mexico, Mary Ellen Mark (1940-2015) attempted in particular to capture the fragility of young acrobats, whether the slim balancing artists of the Chiapas or the fragile Nepalese contortionists attached to the immense caravans that travel faraway lands where they reinvent ancient movements everyday before a captive audience. But she also tried to account for the relations that unite the animals and their trainer by photographing the monkeys, elephants and hippopotamuses that had become the exemplary partners in an improbable community. Black and white suited this use of shadow and light to establish an immaterial repertoire based on universal practices: the photographs of Sarah Moon (1939-) suggest other stories and other encounters, but the sources, from Paris to Saint-Petersburg, are the same. Ben Hopper created strikingly intense work with acrobats' bodies inscribed on a neutral background, their skin covered with earth, chalk or pollen. Like Patrice Bouvier's photographs of the mandrakes – contortionists – his acrobats are imbued with an identical propensity to blend into the symbolic crucible of visual dislocation. The naked contortionist's body photographed by Albert Londe (1858-1917) circa 1900, can be inserted into a similar ledger in a sensitive and evocative census of the determination of the human body to make one forget its apparent rigidity. The painter, Jules Garnier, solicited the same Albert Londe for a series of snapshots from which he created a few illustrations for Hugues Le Roux's work, Les Jeux du cirque et la vie foraine. The photographer set his cameras – more than 50 were used for the occasion – to be able to capture "the intermediary positions that the eye cannot catch," and selected only 7 plates out of 600 produced.

Extreme body

In the work of Beckmann or Louise Bourgeois, the distortion of the body is sometimes pushed until it represents the arc of hysteria defined by professor Charcot: a moving illustration of imbalance par excellence, the backbend is considered, in psychiatry, as the symbolic counterpart to melancholy. Alfred Kubin (1877-1959), Max Klinger (1857-1920) and Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) also created strong, ironic and precise variations of this classical "bridge" pose, the spectacular embodiment of the inverted figure as a graphic and sensual hyphen, which is half metaphor and half reality in the accomplishment of the feat. Artists such as Félicien Rops (1833-1898) and Gus Bofa (1883-1968) outdid each other with their graphic skills, integrating acrobats with supple and evocative bodies into their subversive or unconventional representations, in this elegant game of metaphor.

The space handed down to the decorative arts in the inter-war period offered endless possibilities for integrating very different aesthetic forms, inspired, in particular, by the performing arts and a formidable type of exuberance. Art Deco triumphed from 1925, anchoring its inspirational themes in a rich and dynamic visual repertoire where the acrobat occupied an astonishing place. Such was the case for example, of the sculptor Demeter Chiparus (1886-1947), of Romanian origin, who created elegant figurines in which polychromatic bronze mixed with ivory. The chryselephantine statuettes borrowed as much from mythology and Ancient civilization as from sport and acrobatics: a small population of jugglers, balance artists, animal tamers, circus riders, clowns and acrobats invaded bourgeois interiors, taking up positions on credence tables and pedestal tables, and enabling the imaginary circus world to live alongside other moments of day to day life. Sculpted on wardrobe lintels, coiled up in marble medallions in the image of certain decorative elements of the Moscow Metro, circus silhouettes and characters also enrich the repertoire of visual objects and are turned into charming lampstands, like those of the brand Berger, and like elegant ornaments for the china or ceramic pieces produced mainly by the Choisy, Gien and Creil and Montereau manufacturers.

Today, artists continue to question the figure of the acrobat, as do the sculptor Philippe Arnault or the young artist Manon Paquet for example, who paints immense coloured silhouettes, fragmented and then assembled by pins on large white surfaces. From cave walls to the simplicity of the picture rail, the power of fascination remains intact.

1. Cindy Sherman, Clowns series, 2003-2004.

2. Bruce Nauman, Clown Torture, 1987.

3. Ugo Rondinone, If There were Anywhere but Desert series, 2002.