by Sophie Basch

The circus novel is above all the clown novel. Its success coincided with the years in which Paris was established as the circus capital, between 1870 and 1914.

The impossibility of assigning a historical meaning to time is revealed by an interest in unusual demonstrations after the French Revolution. In literature as in painting and music, much attention was paid to those excluded by society, marginal and fools, pushed into the limelight by he aesthetic of the grotesque, the new governing principle, "the genie of melancholy and meditation, the demon of analysis and controversy1" characteristic of modern times.

A theoretician of romanticism, Hugo created the monstrous figures of Quasimodo and Gwynplaine,"the laughing man", the clown disfigures since childhood. From Musset's Fantasio to Zemlinsky's Dwarf via Verdi's Rigoletto, Leoncavallo's Pailasse and Schoenberg's Pierrot, the grimacing, deformed and fantastical figures appeared in dramatic art.

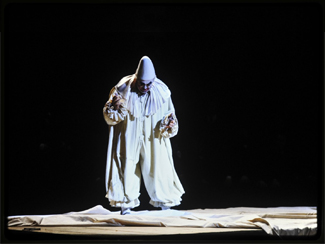

The triumph of the bizarre filled a romantic universe with strange, macabre and trivial creatures. Charles Nodier invented the "frenetic school," and Baudelaire the "satanic school," in the years in which the circus, housing monsters and prodigies, became established as a new religion. From 1831, in Barnave , Jules Janin affirmed that the circus, with its "real blood" and "real tears," was superior to the theatre. In 1859, the Goncourts saw in the circus, "the only talents in the world that are incontestable and absolute like maths, or rather, like the somersault.2" In 1879, Edmond's novel, Les Frères Zemganno , immortalised them. The circus renewed links with the sacred origins of tragedy and resuscitated medieval mysteries.

In big tops, modern man was on a quest for transcendence, which had disappeared form the secularised cupolas and naves. Joris-Karl Huysmans saw in the circus "the masterpiece of new architecture:" "there, in a prodigious cathedral altitude, cast-iron columns fuse with unrivalled audacity. The slender thin stone pillars so admired in some old basilicas seem timid and cumbersome near the jet of these light stems that rise to the gigantic arcs of this revolving ceiling, linked by extraordinary iron networks that stem from every side, blocking, passing each other and tangling up their formidable beams. 3 " Octave Mirbeau compared the decoration of the Cirque d’Été, with "its champlevé enamels set with gems, mosaic shrines, gold plate, and heavy lamé fabrics," to "all the rich service of a dead abbey. 4 "

When Baudelaire described the "English Pierrot" in 1855 in De l’essence du rire , as having the consumptive's pale skin and red cheeks, he defined the French clown, and this model was established among compatriots and then worldwide. The shadow of the clown spread, and invaded the literary landscape. Jules Laforgue imagined a clownish Hamlet. Stéphane Mallarmé praised the "Dorst brothers, these clowns, no, these convulsionaries, no, these strange quadrille dancers, who go by the calm exasperated name of Frétillants5 ». The wild Pierrots of Henri Rivière and Jean Richepin's novels Pierrot (1860) and Braves gens (1886), confirmed the transformation of the amiable, fanciful dreamer into a troubling lunatic. This development had already been described in 1833 by Théophile Gautier: before descending into madness, the painter Onophrius had seen, in the moon, "the pale long face of his close friend Jean-Gaspard Deburau, the great Paillasse des Funambules6" (![]() read the extract). The darling of writers and artists, the sinister clowns of Hanlon Lee , Pierrots in black clothes, accentuated the anxiety given off by these "White men7". Their success at the Folies Bergère in the 1870s, coincided with the beginnings of a doctor, an acrobat in amphitheatres of a different nature. Perceiving the histrionics of these public sessions, Joséphin Péladan wrote, "Theatre people are Charcots.8" (

read the extract). The darling of writers and artists, the sinister clowns of Hanlon Lee , Pierrots in black clothes, accentuated the anxiety given off by these "White men7". Their success at the Folies Bergère in the 1870s, coincided with the beginnings of a doctor, an acrobat in amphitheatres of a different nature. Perceiving the histrionics of these public sessions, Joséphin Péladan wrote, "Theatre people are Charcots.8" (![]() read the extract ), announcing polemical words on the contemporary literary world, and "a Salpêtrière of literature," that contained "enough to astonish, every morning, the Charcots of criticism – those blockhead charlatans." The pamphlet writer concluded: "I laugh at these clowns of hysteria."

read the extract ), announcing polemical words on the contemporary literary world, and "a Salpêtrière of literature," that contained "enough to astonish, every morning, the Charcots of criticism – those blockhead charlatans." The pamphlet writer concluded: "I laugh at these clowns of hysteria."

In the final third of the 19th century, Adolphe Willette's Pierrots, standards of the day and the doubles of a painter attached to the French spirit down to its most grievous aberrations (this "son of the moon" was a dreadful anti-Semite), confirmed the Christianisation of the clown. For the Chat Noir cabaret, Willette composed: Parce Domine a gigantic funereal charivari showing a procession of Pierrots in Calvary. Embroidering on Au clair de la lune, the famous quadrille mistakenly attributed to Lully, Willette multiplied scenes of comic mortification with the Hung Pierrots, and Pierrot at Père Lachaise, entitled De Profundis.

Derision then invaded the literary, artistic and musical landscape. In 1893, Ravel composed his Sérénade Grotesque, in mockery of contemporary musicians (he wrote La Parade in 1896, twenty years before Satie), and dedicated Alborada del gracioso to the Spanish clown in 1904. Picasso came soon after, with his famous study of acrobats inspired by Santiago Rusiñol's piece, La alegria que pasa. Toulouse-Lautrec, who spent part of his life in a circus, had himself photographed disguised as a clown. The salvation of the dwarf was found in the circus, and Marcel Aymé understood this, as he enlarged the cirque Barnaboum dwarf in Le Nain, 1934. More recently in 1994, John Irving's Son of the Circus dives into the redemptive universe of the Indian circus, with its dwarf clowns and little prostitutes saved by the trapeze: "There would never be enough circuses for all the children that the Jesuits thought they save." In a beautiful illustrated children's book, Fred Bernard and François Roca named the circus torso-man – the glory of the big top – Sauveur (Jésus Betz, 2001).

![]() listen to an extract from Alborada del gracioso by Ravel, performed by the Nouvelle Association Symphonique de Paris directed by René Leibowitz, in 1954

listen to an extract from Alborada del gracioso by Ravel, performed by the Nouvelle Association Symphonique de Paris directed by René Leibowitz, in 1954

In 1917, in Remarques sur le clown, André Suarès uses the clown to distinguish between derision and caricature, which applies to mediocre objects and low people: "In Jesus on the cross, if the clown dared, he would immediately see the divinity's puppet, who is going to rot, disperse in the wind and dance a jig. […] One can parody the divine, but not make a caricature of it without dissipating its divine quality, as though swamping a drop of amber in a full vat of washing powder."

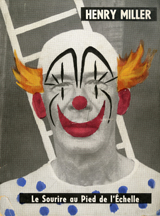

In 1928, the Belgian playwright Michel de Ghelderode published La Transfiguration dans le cirque Escurial. Twenty years later, Henry Miller, a friend of Rouault, Max Jacob, Chagall, and Léger, saw the clown as a "poet in action. He is the story he performs. And it is always the same, never-ending story: adoration, devotion, crucifixion" (The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder, 1948). Later, Angela Carter, not doubting that clowns were the son of men such as Jesus, son of God, evoked the "turbulent resurrection of the clown" ejected from his circus coffin, and discovered, in the mercenary of laughter "the very image of Christ," surrounded by the entire circus company, composed of saints: "Catherine juggling with her wheel. Saint Laurent on his grill, a show of phenomena. Saint Sebastian, the best knife thrower you have ever seen! And Saint Jerome and his clever lion with his paw on a book in a great animal act, who licked the black prostitute and her piano" (Nights at the Circus, 1984). In literature, the 20th century has not renounced the lesson of the 19th century.

![]() listen to extracts from The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder, read by Henry Miller in 1962

listen to extracts from The Smile at the Foot of the Ladder, read by Henry Miller in 1962

1. Victor Hugo, préface to Cromwell, 1828.

![]() read the original edition on Gallica

read the original edition on Gallica

2. Jules and Edmond de Goncourt, Journal. Mémoires de la vie littéraire, Robert Laffont, « Bouquins », 1989, t. II, p. 491.

![]() read the original edition on Gallica

read the original edition on Gallica

3. J.-K. Huysmans, « Le Salon officiel de 1881 » in L’Art moderne, UGE, 1975, p. 198-199.

![]() lire le texte sur Gallica

lire le texte sur Gallica

4. Octave Mirbeau, L’Écuyère [1882], in Œuvre romanesque, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 2000, t. I, p. 787.

![]() read the text on the éditions du Boucher website

read the text on the éditions du Boucher website

5. Stéphane Mallarmé, in La Dernière Mode, fourth part, October 18th 1874, p. 8.

6. Théophile Gautier, Les Jeunes France [1833], in Œuvres, Robert Laffont, « Bouquins », 1995, p. 57.

![]() read the original edition on Gallica

read the original edition on Gallica

7. Notion derived form the term "White face," used by turn of the century symbolist poets such as Albert Giraud, alias Emile Albert Kayenberg – 1860-1929-(Pierrot Lunaire: Rondels bergamasques (1884), Pierrot Narcisse songe d’hiver, comédie fiabesque(1887) and Héros et pierrots (1898), set to music by Arnold Shönberg, first performed in 1912

8. Joséphin Péladan, La Décadence latine, éthopée, VI : la Victoire du mari, Paris, Dentu, 1889, p. 27.

![]() read the text on Gallica

read the text on Gallica