by Pascal Jacob

Circus disciplines originating from war are numerous, but the hand to hand act is perhaps the only one that borrows both from bare, hand-to-hand combat, and evokes the notions of engaging and confrontation, as well as embracing and complicity. References to wrestling, considered as a possible ancestor, are recurrent in very different cultures, such as the Breton Gouren, established in Armorique in the 4th century, and modelled on a succession of short, seven-minute fights carried out on a think sawdust mat. In addition there is the Korean Ssireum, developed in the 1st century B.C. and done in a circular surface covered with fine sand and the Indian Kushti. The Manchu Buku and the Mongol Böhk, both stem from the Chinese Jiaoli, a combat technique associated with the legendary Cors Battle, an ancestral technique that founded and codified the hand-to-hand technique, hoop jumping and the martial arts. These references nourish the discipline which has seen fluid sequences of movement replace the brutality of combat.

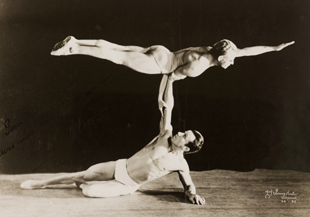

The transformation occurred with an act created by the Athenas, a duo presented at the Olympia in 1921, composed of André Ackermann, a sculptor trained in the Beaux Arts, and Raymond Manvielle, a gymnast from the Joinville School. The Athenas created Art et force, a powerful blend of immobile artistic poses and the raw energy of floor acrobatics completed by the slow motion execution of an ancient fist fight to a score specially written by composer Jean Nouguès. The fashion for the Olympic spirit combined with developments in physical culture drove the enthusiasm for these spectacular physical games. Remember that the word athlete, from the Greek athlos, means combat…

Strength and beauty

By combing the elegance of acrobatic lifts with the reconstitution of an ancient combat form, the Athenas laid the foundations of a new genre, quickly identified as the hand to hand discipline. The vanguard and pioneers, they were soon imitated, and duos appeared all over Europe. Enrico Mangini, a young Italian athlete, worked with several successive partners including Raymond Manvielle when the latter separated from Ackermann, and was a key figure in hand to hand evolution. With his numerous partners, his exercises gained popularity and he continually created new emulators. Inspired by the perfection of classical statues, static hand to hand was the first step towards recognition of a new technique hat was much appreciated on the music hall scene, where it was seen as a natural counterpoint to the beauty of the dancers, and as a symbol of simplicity in contrast to the profusion of feathers and diamante that characterized performances at the time.

The notion of acrobatic lifts sums up the framework of juxtaposed figures aimed at structuring an act of a few minutes, in which skilful strength, placed in the service of a slow sequence, is the keystone of its success. At the end of the 1980s, the Chen Brothers, traditional family Portuguese acrobats, created an act that was constructed like a slow development with, for the main part, absolutely perfect planks. This act was somewhat the result of a slow process of filtration that had gradually evacuated all pugilistic references, leaving only a pure series of instants of magnificent strength, transcended by its own skill. The four Pellegrinis, the Père brothers and the Sharkovs were bare-chested like most of their counterparts. The Alexis Brothers played with their sculpted bodies like an additional trick and created their act in a spirit of pure demonstration, but with a hint of humour that gave their performance a particular flavour. The balance of power was decisive, and the closer the partners were in size and weight, the more impressive the performance. Enrico Mangini grasped this when he in turn separated from Raymond Manvielle, who he carried effortlessly, for heavier partners with a physique similar to his own – that of a former champion weightlifter.

Masculine/feminine

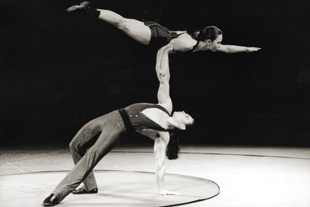

Although the first duos were mainly masculine, mixed duos gradually appeared in which either the man or the woman could be carried. Eric and Amelie were trained by Claude Victoria at the Annie Fratellini national circus school at the end of the 1980s, Virgile and Sophie graduated from the National centre for circus arts in Châlons-en-Champagne in 1987, and the You and Me duo and Paradise duo were both trained at the Academy of circus and variety arts in Kiev in the early 2000s. All of the above embodied this development in hand to hand, in which successive figures could serve a propos. The "la main s'affaire" duo, trained at the Toulouse centre for circus arts and at the Kiev Academy, incorporated humour, like the Goldini family, where the young woman was taller than her partner, adding an effect of distortion to the balance of power. In an intermediate register between strength and fragility, the duo created by the Guangdong military company in 2002 took on the codes of acrobatic lifts, but transcended them through the extraordinary technical skill of the two partners. The flyer developed work on point, balancing on the shoulder or the head of her pusher, juxtaposing the elegance of classical ballet with the purity of an accomplished acrobat's techniques.

Cnac graduates Edward Aleman and Wilmer Marquez founded the El Nucleo company and created the Quien Soy? show from their hand to hand practice. Since 1994, with the Acrostiches, they had considered this a pretext for a mono-disciplinary artistic form, and a way of exploring the mysteries of acrobatics, in the same way as Alexandre Fray and Frédéric Arsenault's Un Loup pour l'homme company had done. With them, hand to hand became a hybrid with dance, but moreover, became more complex in its approach to space, playing with its technical duality, mixing lifts while emphasizing a dynamic approach to the discipline. Victor and Kati – Victor Cathala and Kati Pikkarainen – as well as Anne de Buck and Mikis Minnier-Matsakis, trained at the National centre for circus arts, founded Cirque Aital and the Fardeau company, incorporating respectively humour and silence. This was a way to highlight the sacred essence of the discipline by bringing it closer to ritual and traditional choreographic practices. The notion of lifts came largely from dance – from classical ballet to Puerto Rican salsa, and from acrobatic rock to Argentinian tango, but is also present in acrosport, figure skating and Aikido.

Dynamics

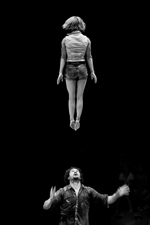

The origins of dynamic hand to hand draw on those of jumping and create a completely different balance of power by emphasizing propulsion and valorising the paradox of rejection and attachment. If static hand to hand praises the intense slowness and the decomposition of a movement pushed to its height, then dynamic lifts were clearly the domain of the explosive, and often opened up between anger, confrontation, desire and romanticism.

The technique borrows from the register of human propulsion to develop a repertory of figures often coded by the artists themselves. The rigodon, is an ancient jump technique that sees the flyer pushed by one foot, creating the necessary impetus for him to turn a somersault. It is the equivalent of a pitch tuck in acrobatic dance and was the early beginnings of dynamic hand to hand. Acrobatic dance, initiated in the United States by Sherman Coates around 1900, constituted a prelude to what the second half of the 20th century would consider as hand to hand as it is generally accepted. Gradually, acrobatic and choreographic composition would make the discipline unique, provoking the creation of numerous masculine or mixed duos. In 2005, the Iroshnikov brothers, trained in Kiev, created a sensation at the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain with an extraordinarily rich act. Simply dressed in black, one wore gloves and the other's face was hidden behind a fringe of blond hair. In a couple of minutes, they developed a remarkably fluid sequence. Their duo combined Christ like references with the symbolic power of working in a partnership, in which mastery and precision were exemplary. In a completely different register, Sébastien Soldevila and Emilie Bonnavaud constructed a taut duo with fast, precise sequences. They embody the remarkable tonality of amorous jousting in which the figures are implicitly linked to the choreography and underlie a propos that is both simple and founding. The complicity between the pusher and the flyer is decisive, but today there has been a genuine development in the very approach to the work, whereby the harmony between the two partners is more subtle, the roles are not as clear-cut, and pusher and flyer emphasize equality rather than difference.

- Man walking on his head, four pictures by Jules Beau, 1903.

Interview