by Pascal Jacob

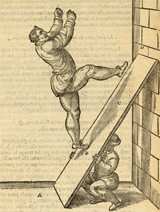

When Archangelo Tuccaro, "Saltarin du Roy" published his Trois dialogues de l'exercice de sauter et voltiger en l'air in 1599, he helped make acrobatics popular and followed on from the De Arte Gymnastica work published in Venice in 1569, by Girolamo Mercuriale. These two books were the first theoretical works on acrobatic movement, but they suggest above all that acrobatics follow a social and literary perspective through the emergence of a physical culture in the literal sense of the word.

From ritual to show

Defining acrobatics precisely is a dangerous exercise as the term now designates, as it did originally, a multitude of disciplines that all stem from the same initial concept. From the Greek acros, meaning extreme, and bates meaning walk, or move forward, the term led to an idea of progression but also of a gap between acrobats and mere mortals. It is a tacit designation of all those who play with the principle of extension and inversion, in other words dancers, tight rope walkers and floor jumpers. They are all acrobats. They "move around on their extremities," i.e. their hands and toes, and founded the first, remarkable and symbolic artistic diaspora. The medieval juggler, a wit, singer and manipulator of objects, is also sometimes an acrobat. Capable of jumping, balancing on one leg or of walking on his hands, he has multiple skills and identifies with an entire cast. The term "acrobat" has, up to a certain point, been substituted for that of "juggler," which now designates not only a branch of disciplines based on the manipulation of objects, but also the "saltimbanco," who now has a negative connotation, and "tumbler," which defines all those whose profession is jumping and performing tumbling sequences. The actual practise of tumbling is of course influenced by this.

The structure of forms

What characterises the importance of acrobatics, is the development of a terminology linked to its practice. The Greek cybisteter, and the Latin cernuus, stemming from the verb cernuo, meaning, "to fall head forwards," or "to tumble," are comparable to a form of tumbler that we now define as balance artists. Funambulus and oreibate identify the wire artists. Acrobatics is a tree structure with many branches, and has a vocabulary shared by all disciplines. It is a spectacular and universal language as well as an intuitive and dynamic game based on the body and its explosive quality, its power and its elegance.

However the game, if not the stakes, is not in fact gratuitous. This frenetic energy, power and elegance can be seen in a fresco discovered in Knossos, painted 1500 years B.C., portraying young acrobats jumping over the bulls of a running bull. For those tempted to see the origins of bullfighting therein, it should be said that the posture of the jumpers is revelatory more of a conscious jump rather than a simple leap out of the way of the animal's horns. This posture, in fact, which demonstrates skilful flexibility, also refers to other frescoes, developed two thousand years before our era and discovered in Egypt, like the outlines of physical science as spectacular as it is sacred.

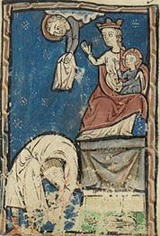

Originally, acrobatics both formulated a rite, and revealed secret wisdom. During ancient times in Sumer, in Egypt, or at the outskirts of the Indus, its practice was often linked to funeral ceremonies. Jumps and flexibility had a "warding off" function by opposing the present death with a sequence of figures representing the irrepressible vitality of life. By symbolically dominating his body, the acrobat is a figure of progress: there is no inversion that cannot be righted, in this source of rebirth that conveys the transition from one world to the next. Today, this funerary dimension still exists in the Taoist liturgy, where certain ceremonies are performed by acrobat-priests. They illustrate each of the steps of the deceased's journey to the afterlife through symbolic performances including the manipulation of objects, jumps and floor acrobatics. The ritual can take place in the open air, in the centre of town without being interrupted by the disturbances of daily life.

Inspiration

The roots of acrobatics are global and date back thousands of years. Ritual imitation of animal behaviour lies behind the development of the first acrobatic forms. To convince the gods to place the greatest number of prey on the hunter's path, a group would imitate certain creatures in the most explicit way, by wearing feathers, horns or skins for increased realism and to dissipate any hesitation on the part of the benevolent powers. Speed, strength, agility and flexibility characterise numerous species, and by imitating them, by selecting the most talented individuals from the clan, men would gradually acquire the same skills. An understanding of these strange skills would encourage competition for precision and talent.

When communities of hunter-gathers became sedentary societies of agricultural farmers and animal breeders, they retained the memory of these hunting rituals and gradually turned them into a profane, artistic form, and show acrobatics was born. Circus techniques such as the Chinese poles, contortion, balancing acts, pyramids, hand to hand lifts etc., all arose from these games of imitation and the pleasure of competing to climb a tree as quickly as possible, from the ability to make crawling look like second nature, and from the need to support and lift oneself higher and higher towards the stars. These secular figures and these orchestic rituals echoed like a fertile memory: contemporary acrobatics has no other sources, although it has, of course, continued to develop and grow richer, from this powerful and symbolic base, nourished by hybrid forms and interpretations.

The caravans that tirelessly traverse the faraway lands of Central Asia to deposit the most extraordinary merchandise at the gates of Europe, like the warrior expeditions of Genghis Khan and his descendants who appropriated men and treasure, ensured the link and the spreading of games of skill, performance and masterful manipulation. All along the Silk Route, linking East and West, a universal repertory grew up, through encounters, confrontations, exchanges and aggregates, in a sort of inventory of feats, creating an intuitive footbridge between men and civilizations.

The Tzigane Migration

Halfway through a two thousand-year old history, around the 10th century, an entire community set off on a march to escape famine and the exactions of other communities. This immense, exodus-like migration was a metaphor for what would constitute the next ten centuries: itinerancy was to be their lifestyle and moreover their objective. Guided by the stars, organized in companies of several dozen, or even several hundred individuals, the Tzigane people set off on the longest march in their history. They abandoned the North of India and slowly, at the pace of man and animal, they went in quest of a safer land where they could protect their families. The hazardous road was endless, and it took several centuries to cover the thousands of kilometres and arrive, for some of then, at the threshold of Europe, around the 14th century. They brought strange and new knowledge, sometimes inherited form ancient forms, half myth, half ritual.

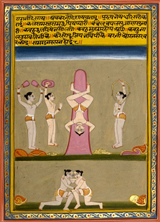

The Kalarippayatt is a warrior and acrobatic dance originating in Kerala, a southern Indian state, the first traces of which can be seen in palm leaf drawings dating back to the 2nd century B.C. The Kalarippayatt was codified in the 12th century and knew a golden age between the 15th and 17th centuries. Considered the ancestor of martial arts, this dance is nourished by powerful references. It is inspired buy the Dravidian culture, linked to knowledge of the animal and plant kingdoms, as well as the Buddhist culture, through the energetic and Aryan science of the body, with holistic techniques of domination and conquest. Its followers were led into the kalari, a small, sand-covered arena measuring 14 x 7 metres, where they executed prodigious jumps and were also capable of moving silently, developing a form of animal mimetism. The energy and strength demonstrated gave a dramatic element to the confrontations, magnified by the both fluid and precise movements. At the other extremity of this war dance, the Gotipua is a pacific dance from the state of Orissa, performed, since the 16th century, by young boys dressed in shimmering women's costumes. A blend of contortion and acrobatics, the Gotipua honours the god Krishna and offers an astonishing synthesis between performance and choreography, supported by the percussive rhythms, amplified by the rhythmic hammering of the dancers' feet.

The Mallakhamb, a little-known practice begun in India in the 12th century, stemming from Malla, which means strongman and khamb, which means pillar, is a sporting discipline codified in the 18th century in the state of Maharastra and widely developed in the following century at the instigation of Sir Balambhatt Dada Deodhar. Practiced with a three metre high teak or rosewood pole, the aim was to perform a maximum number of figures in one minute thirty seconds. The pole was carefully polishes and oiled to avoid any roughness that might injure the participants, dressed simply in an orange loincloth. Holds and combinations were dramatic, combining extremely flexible shoulders with strength and speed. Purely gymnastic, and very structures since 1958 with regional and national competitions and a very precise scoring system, the Mallakhamb, removed from its sporting context, is nevertheless regularly presents as an attraction in its own right. In 2009, the India show, created by Franco Dragone for Prime Time Entertainment, revealed a collective of 8 Mallakhamb performers, completely choreographed and removed from any gymnastic connotation. The Dai Show, a permanent show also created by Franco Dragone in Xishuangbanna in 2015, included a Mallakhamb sequence.

These choreographic and acrobatic forms steeped in numerous sacred references concur with other references that structure the development of acrobatics as much as our vision of this discipline. For the Ghanaian Anyi, at certain ceremonies a circle is traced on the ground with kaolin powder to constitute a sacred and ephemeral space. Within this circular space, several officiants perform defined roles that embody, mainly, clowns and demons, identified by their makeup and physical type.

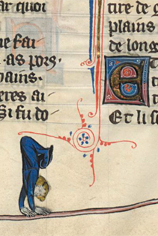

Jumps, tumbles, and grotesque warding off movements create a symbolic vocabulary comprehensible to the initiated and the audience, and which is similar both to theatre, dance and acrobatics. The study of incunabula, manuscripts and books of hours reveals some pleasant surprises: there, in astonishingly fresh illuminations, in the margins of knowingly traced lines, jugglers dance and acrobats perform. A wonderful illustrated corpus suggests just how the skill of a few, managed to transcend the imagination of many others. Between two gold-flecked columns, embellished with two drops of carmine, written in the margins of a collection of eternal thoughts and references, a lone contortionist embodies the ambivalence of his skill. Comparable to a demon as much as a tutelary figure of inversion and evolution, he enhances, in a very precise manner, the fragility of existence, and reflects the vanity of the spectator. Showing incarnation and transition, with every balancing act, the acrobat once again performs the intensity of the passage of physical death and spiritual resurrection, as well as inserting himself into the artistic sphere of time.

At the source of the Banco

In parallel, the cathedral construction sites represented a formidable laboratory for integrating acrobatic movement into the medieval visual vocabulary. Acrobats and jugglers were inscribed on stone columns as well as in the bas-relief three-dimensional frescoes destined to decorate gates, in a sculpted restitution of scenes bringing to life the Mysteries performed on the church square. The crafted, sacralised body was dislocated or triumphant, and the acrobat symbolised and reflected the immemorial fascination for games of agility and the evocative power of extraordinary movements as well as a new alphabet and vocabulary. Century after century, branches of techniques and disciplines gradually transformed into a powerful shared trunk. This is how some of the fundamental disciplines of acrobatics arose, grew and blended, and their movements and positions gradually came to constitute a universal repertory that formed the basis of the "Grande Banque d'Occident" (literally the "Great Occidental Bench"). Here the word banque, means diaspora or community again. The word stems form the term Saltimbanco, from the old Italian saltare in banco, literally, to jump on a bench, stage, or the wandering entertainers' platform, from where artists could dominate the crowd to perform their acts and spin their yarns.

From the word saltimbanco, which is both noble and pejorative, strange and explicit branches of words have developed in French: from banquette (bench seat)to banquine (acrobatic act) and from banque (bank)to banquistes (touts), they all share the beguiling origins in which the "bench" is sometimes that of the moneychanger, in other words, the banker… An air of money and entertainment, a partnership that has the allure of a premonition and an ambiguous proximity provide an enduring relation. The banquette is a small mound of earth or a wooden fence topped with red velvet that hems in the ring and constitutes a symbolic and impassable rampart. The banquine act is a human propulsion technique that sees two spotters push and catch a flyer, while the word banque identifies the ensemble of the diaspora composed of banquistes.

The end of a world

The saltimbanques who trod their paths and performed randomly along the way, a recurrent phenomenon since Thespis and his chariot in Greece, were considered harmful and were excommunicated in the same way as actors had been since the 4th century and the Synod of Elvira in Spain in 305. It was then difficult to assimilate these "vagabonds" to a social body, especially as a sedentary lifestyle was the norm, as were famines, dues to bad harvests, plundering by lawless troops of mercenaries or wagoners, and the epidemics that raged in certain regions, which did not encourage tolerance for difference in any shape or form. The traveller, the other, was therefore inevitably considered as responsible for all the ills of the century. Sometimes an alternative was offered in the shape of corporations, guilds and wandering minstrels who gathered together, federated and protected those representing the same profession. And, like butchers, tailors and tanners, jugglers sometimes had a street, a district or even a hospital reserved for them. Part of the fabric of the city, they thereby acquired a semblance of respectability. This idea suggests the outline of the company, and therefore the clan, family and dynasty. Belonging to the same bloodline was a notion that founded corporations. This was a symbolic link with the organization of former guilds, but in which talent opened doors and was a raison d'être.

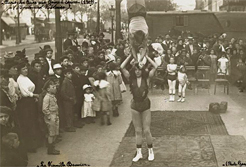

The big fairs, which brought together multiple activities and constituted gigantic meeting points, have always been a favoured place for acrobats of all origins. Some fairs even provided them with entire districts, small streets lined with lodges wherein rope dancers and object manipulators performed, while trainers showed their animals. Vibrant urban territories where science, spectacle and commerce alternated and cohabited, the fairs attracted thousands of onlookers constituting a regular, and moreover captive, audience. Sellers of creams and ointments – charlatans from the start – sometimes partnered with skilful acrobats to peddle their products. A jump, a pirouette or a witty word, was enough to attract a customer to the foot of the platform where, probably fascinated, he would succumb to the sales patter and walk away with a miraculous balm or powder.

In 1719, a royal edict, obtained after a brave struggle by the Comédie Française to put an end to the competition, judged as unfair, eventually regulated the heated extravagance of the fair, moreover too often associated with excess and a dispute that rendered power fragile. Gradually reduced and forbidden, the fairs threw out numerous acrobats who had contributed to their development and their fortune. During the second half of the 18th century, rope dancers, jugglers and acrobats forged partnerships with equestrian acrobats.

Inspired, influenced and nourished by acrobatics, the modern circus came on stage for the first act in its history.