by Pascal Jacob

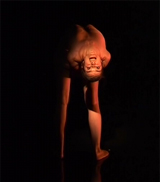

Founded in 2010 by Antonia Kuzmanic and Jakov Labrovic, Room 100 is an experimental company from Split, in Croatia. Their first show, C8H11NO2, was created by self-taught artists using a combination of contortion, dislocation, Japanese Butoh and break dancing. The ensemble is bathed in a very sombre ambience, emphasized by the live music of David Gazde, performed on electric oscillators. An artistic form that combines the body and the installation, C8H11NO2 suggests a radical and physical vision of schizophrenia: the work is intense and disturbing, but also reveals itself to be intimate and mesmerizing. It exposes, in particular, this quest for meaning, which has crossed the circus arts and their successive transformations for almost forty years.

Room 100 is a good illustration of this new age of acrobatics, which is still a unifying language, but in the service of another vision, another type of body language, other rituals, and other compositions. The alphabet and vocabulary of acrobatics is based on the same fundamental principles as for traditional acts, but it probably questions further the relation to the world of the performer, and helps distinguish branches of postures in the service of a statement. Since the beginnings of the Soviet circus at the end of the 1920s, the notion of meaning, composition and dramatic art has been decisive: potentially enriched by a narrative principle, it constitutes the framework of the performance, modelling its rough edges and density, and helping to anchor the contemporary circus in the world's vibration.

Transformations of the acrobatic movement are also confirmed in the choice of intention and elimination. The dilution of emphasis and grandiloquence, cherished by more conventional forms, is a significant marker in order to appreciate a development towards simplicity. Deconstructing the feat for itself, leads to a dissolution of the "act" form, in a development towards an abstract form, in which intention is as important as accomplishment. In the research of Chloé Moglia and Mélissa Von Vepy on uncommon apparatus, from Rhizikon's blackboard to a hanging mirror for the aptly named Miroir, Miroir, these appropriations are spectacular and powerfully theatrical. The work of d’Angela Laurier, nourished by her own story, transcends the practice of contortion, exacerbating its fragility and tracing a life path with touches of beauty that are as dazzling as they are despairing.

Into the void

Historically, the circus ring was empty. It was its best asset: a playground open to any possibility, a space that provided endless latitude for trying everything. Symbolically, the structure of the performance was based on the principle of ebb and flow, in an endless system of comings and goings for the fast installation of material and apparatus. The empty space, almost unencumbered, forged dramatic art at the circus. This principle was demolished by the 1996 graduating class of the Cnac, (National centre for circus arts) in Châlons-en-Champagne, with their show Sur l’air de Marlborough, in which the director and choreographer François Verret, filled the ring with a gigantic metal structure, which incorporated all the necessary apparatus for the performance, and continually modified the audience's point of view.

Companies such as La Meute and Race Horse saturate the space with a multitude of apparatus, accessories, and stage elements that they favour, manipulate and abandon throughout the performance. In Super Sunday, the Race Horse acrobats move from a trebuchet to a death wheel, and plot a catalogue of pretexts for the performance, which is a game based on the notion of risk, a dynamic construction similar to a hungry exploration for a maximum number of techniques, and a Don Juan style inventory motivated by the conquest and mastery of that which has kindled acrobats' imaginations since childhood.

The Yvan Mosjoukine collective's De nos jours (Notes on the circus), has neither drums nor trumpets, glitter or sequins, yet re-appropriates circus and fairground artifice with a communicative energy and a feeling for the caesura reminiscent of the form of Peter Greenaway's show 100 Objects to Represent the World, a reflection on stance and sequence, which are notions that resonate with the show Irritation directed by Rolf Alme at the Brussels École supérieure des arts du cirque in 2008.

Each student was invited to pronounce a few sentences, alone, using a microphone placed front of stage. The student's schoolmates answered in an often-humorous chorus. Before leaving the stage, the student would perform the most complex figure from their speciality discipline, in a precipitate of several years of training, attempts, failures and successes. This quest for the essential went well with this idea of simplicity and of valuing the idea of stance rather than the act.

Questioning

The notion of meaning is decisive: contemporary acrobatics serve an intention, and a narrative process, constituting the framework of the performance, modelling its rough edges and its density. Detached from the one-upmanship of the exploit and the purely demonstrative register, the contemporary circus values the idea of an indirect performance, such as in Sans Objet created by Aurélien Bory, in which an impressive robot covered with a plastic tarpaulin models the space and multiplies forms and reflections. Beyond the abstract nature of the machine, the presence of human bodies, which complete, surround and control it, form a different awareness of risk, and encourage a heightened perception of the movements stimulated by a steel structure. Far from the somersault, the feat is nevertheless intact and establishes itself, without ambiguity, as a slow acrobatic and choreographic process that is demanding and … spectacular.

Plexus, with the dancer Kaori Ito, shows another way of questioning the human being and of making him face endless obstacles before he can make his way through thousands of glistening, shimmering nylon threads, in which he gets lost, then carries on, part puppet, part prisoner. The space conditions his movements, distinguishing them and identifying them, crafting a troubling portrait inspired by the nervous system, that sometimes-paradoxical Achilles heel of over-confident humans.

Sometimes, it is the rediscovery of an ancient discipline, re-visited through the prism of meaning and symbol, that builds a surprising bridge between history and the contemporary. By re-appropriating the technique of hanging by the hair, Sanja Kosonen and Elice Abonce Muhonen, a tightrope walker and a trapeze artist, have created Capilotractées, a fascinating series of eight suspension sequences in a powerful and moving show in which hair is an allegory and a pretext for distortion. The double-bladed sword of the hanging performer questions the principle of repetition, this obsession that verges on the absurd, marked out by a series of rituals to create a form of circus that wants to be colourful and uncluttered, oscillating with humour between Sisyphus and Babel. But it is also a fascinating variation on the theme of death, with a second, very real hanging, when the rope, wrapped around the neck, is let go, then stopped at the last second. But this terribly acute movement that restores pure anguish is the stock of numerous fairground tumblers and the brutal essence of multiple circus performances. This game of death and chance, a principle characteristic of the modern circus since the 19th century, aims to be more metaphor than real, even though the fascination for danger as spice remains intact.

Distances

What Yoann Bourgeois develops is an implementation of the acrobat's or dancer's body, in a context or situation that can sometimes disturb their balance. In Celui qui tombe, six characters are faced with a large mobile platform that may be tilted, raised, or lowered at different angles and speeds. It is a permanent quest for balance, and a magnificent pretext for developing links, relations, and situations in a restricted space, an unstable playground that clearly reflects our world. This questioning evokes concerns and awareness, as well as the desire to understand and to share a mixture of worry and hope. Therein lies the privilege of contemporary circus, more in a position to make a statement about the place, than to be satisfied with offering a time-space performance lacking in depth. Today's circus arts use the dilation of time, stretching the acrobatic movement, until perhaps they occasionally reach a disembodiment of the circus.

The acceptance of blood, sweat, mud, destruction, imperfection, and falls, form the basis of a different approach, and a different perception, which could be an interpretation of the very essence of the circus.

Since Où ça ? Johann Le Guillerm has manipulated time and played with his audiences' senses, walking them along steep paths, where uncertain movements, throwing an axe for example, might be repeated until they are fully mastered, even if that takes several dozen attempts. This refusal of an obligatory tempo, this choice of probability, and uncertainty, accepted as elements of dramatic art, contrast with a perfectly choreographed tradition in which one of the founding principles is never to fail. Sébastien Wojdan questions and plays with the "terror" of proximity by placing his "risk fragments" in contact with his audience, who are suddenly involved, and almost play an active role in an artistic form that revisits the fairground exhibition codes. This proximity sometimes has an aesthetic value: this affirmed deadly contact, banished by the traditional circus – aware of its danger, but not wanting to broadcast the fact – imbues the work of the Australian Acrobat company, who do not reject blood, and develop a raw form of acrobatics, haunted by shock and tears. Abandoning the smooth, and artificial, old-fashioned perfection is perhaps what characterizes transformations in contemporary circus. This does not however, eliminate the purity of the acrobatic movement, but its truth is multiplied by the meaning it has now acquired.

Intentions

The succession of thrusts, lifts, elevations and human constructions that sometimes border on powerful evocations of the Deposition, form the vocabulary of the XY collective, a company whose principal material is hand-to-hand. Far beyond the always slightly vain demonstration, they develop a strikingly beautiful language. Columns and propulsions help develop a rich composition in an architecture of deconstruction that is prodigiously intense. The simulation of collective combat is a powerful sequence in the creation, Il n’est pas encore minuit. Here, intentions are truthful, balanced in terms of precise bodywork and performance, returning to the framework of the original circus, part ritual, and part outlet. This dimension is shared by the Un loup pour l’homme company, for whom each creation is a commitment, as well as a confrontation between the acrobats' bodies and the space that contains them.

Although in a different register, acrobats such as Spencer Novitch and Arthur Cadre use only the lines of their bodies to create meaning somewhere between humour and skill, the most significant dimension in the accomplishment of the contemporary acrobatic movement, is probably to be found in a process of complicity with the apparatus, which is the inspiration for new figures, and a different level of physical involvement.

It is within this tension with the object, regardless of its size, that the structure of new visual and technical compositions resides. The artist suggest new balance postures and modifies both his own, and the audience's perception of movement. He questions the fundamentals of a discipline, and the repertoire of expected figures, and offers an alternative to the established codes of that discipline. Above all, he determines the possibility of developing a secular apparatus in a contemporary perspective, as a pretext for inducing another skill, and a related new type of appreciation for the entire form. This is a reflection, beyond a single technique, of acrobatics and the circus.