by Pascal Jacob

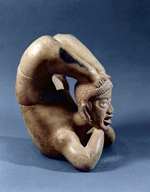

Linked to shamanic practices, certain acrobatic exercises are similar to primitive rites. They place the subject in the hands of an invoked divinity, or challenge the subject in the eyes of the community by giving them mastery of a superhuman skill.

Acrobats and dancers cross the threshold of gravity, pushed to the extreme of what is humanly possible, expecting to be delivered up to a protective power, which will then act within them and through them, so that their movements identify with those of the creative divinity, revealing its presence.

In Cambodia for example, the slow, precise dislocation of each body part, from the back to the fingers, enables the dancers to free themselves from too-human gestures and thereby create movements associated with mythical incarnations. There is nothing insignificant in this process:

each position functions as a transcended imitation of supernatural beings. River and forest powers are invoked and summoned, to confirm and uphold the ceremonial proceedings. In this particular context, acrobatics symbolise attaining a superhuman condition. It is a bodily ecstasy. And everything that covers the flesh – powder, oil, skin or feathers – helps to fulfil the mystery of elevation and transcendence. Today, Asian and Western contortionists do essentially the same thing, but the register is essentially secular and spectacular.

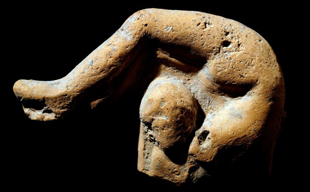

The phenomenon of bodily dislocation resides for many in the feeling of repulsion felt by certain audience members when they watch a contortionist act. Arevik Seyranyan, who, as part of his act, dislocates his shoulders and shuts himself inside a minuscule box with his sister in his act, or Sacha la Grenouille, who can rotate his pelvis almost completely, inevitably provoke a disturbing impression of a body ill-treated.

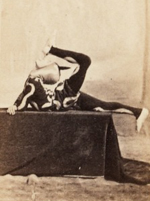

Elegance et flexibility

There is also probably a quick and easy comparison to make with the reputation of the serpent. This impression is sometimes reinforced in the history of the discipline in theatrical playlets in which contortionists wear close-fitting costumes textured to resemble snakeskin. The reptilian nature of often-impressive prowess found its place in 19th century pantomimes and looks extremely effective against a simple cardboard jungle backdrop.

Although contortionists no longer drink vinegar to make their cartilage more supple, or even to dissolve such cartilage as might hinder their flexibility, it is nevertheless logical that a certain physical, or physiological disposition is required in order to practice dislocation, or in less frightening terms, flexibility exercises. In Russia, the word "rubber" is used to identify contortion and to remove all ambiguity regarding the shape and basis of the discipline. In forward bends, back bends and pelvic rotation, the body is solicited to provide a sensation of "sinuosity" as much as fluidity in the structure and sequence of postures. The entire approach to modern contortionism resides in a quest for elegance and distance, to transform "supernatural" flexibility into a flowing and elegant body language. In the 1960s, the contortionist Fatima Zohra helped to confer an aura of charm and sensuality on the discipline, while Archie and Diana Bennett's duo added strength and grace.

From then on, the border between balancing acts and contortion has sometimes been blurred, but acrobats Anastasia Mazur, Lunga and Natalia Vasiliuk, embody a new generation of flexibility artists. They do not renounce the spectacular dimension of their predecessors, but they add a hint of tension or irony, and the particular blend of abandon and nonchalance that creates virtuosity.