by Pascal Jacob

"I had often been struck by the ease with which pianists can read and perform at sight the most difficult pieces. I saw that, by practice, it would be possible to create a certainty of perception and facility of touch, rendering it easy for the artist to attend to several things simultaneously, while his hands were busy employed with some complicated task. This faculty I wished to acquire and apply to sleight-of-hand; (…) I had recourse to the juggler’s art, in which I hoped to meet with an analogous result".

Robert-Houdin, Memoirs of Robert-Houdin: Ambassador, Author, and Conjurer. Written by Himself, ed. Dr. R Shelton Mackenzie, Philadelphia, G.G. Evans, 1859.

Legends and realities

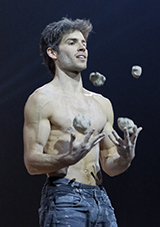

For several millennia, we have been juggling with fruits, leather balls or clay balls... This last material has been reintroduced by the young juggler Jimmy Gonzales; whose handling of clay balls has led to an exceptional performance in an exhibition dedicated to the sculptor Auguste Rodin at the Musée des Beaux-arts de Montréal. This spectacular echo of the past reinforces the intuition of a spontaneous, ritualised and coded practice, but one that can flourish from rudimentary elements, literally "within reach". This extreme simplicity gives an often-playful practice a character of immediacy and proximity. It is through a patient system of filtration and stratification of the manipulations that several aspects of modern juggling have been developed. Many Greek vases, craters and rhytons shaped and painted around 450 BCE represent male and female jugglers. Their fluency and virtuosity seem undeniable. The perceptible flexibility of the bodies suggests acrobatic mobility associated with the manipulation of leather or wood balls.

Whether it is the Chinese Lan Zi, able to juggle with seven swords under the reign of the Song dynasty, or the female Egyptian jugglers represented on the walls of a tomb on the site of Beni Hasan, or Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel who juggles with ten burning torches or Roman legionnaires trained in juggling to acquire additional weapon handling ability, it is dexterity that unifies these practices identified throughout the ages. They revolve around entertainment, ritual and warfare, but above all they share the same objective: to acquire a form of virtuosity that is both useful and invariably astonishing. Tulchinne, the buffoon of the legendary Conaire Mór, the high king of Ireland whose reign could be contemporary with the advent of Christ, is able to juggle with nine swords, nine silver shields and nine gold apples.

The story of Séadanda, another legendary Celtic hero renamed Cúchulainn when he killed the ferocious dog that threatened to slit his throat at the age of 5, draws from the same sources and does not deviate from the rule. Nicknamed the walker or contortionist, especially for his agility to blend into multiple appearances, he is able to juggle with nine apples and as such attests to an undeniable virtuosity. He thus anchors juggling in the register of extraordinary abilities likely to identify a character when it comes to bringing out his exploits.

Skills

Sela and Mele, Moana Takai or Sulia Fonua have several things in common. They are women, they are citizens of the Kingdom of Tonga, but above all they are jugglers. Just out of their teens, young street vendors or kind retirees, they share a strange know-how passed down from countless generations. They all practice Hiko, an everyday form of juggling that can be accomplished with a simple impulse by picking a few green and slightly ovoid fruits that are within reach. A 1793 print illustrates this spectacular ability, but the origins of this manipulation, only mastered by the girls and women of the kingdom, seem to date back to the time when the population first settled in the territory. Most of them juggle with ease with three "balls", or even four or five, participating in friendly competitions, but very few have the hope of reaching the exceptional and legendary manipulation with ten fruits! This "impulsive" juggling is accompanied by sung words that practitioners do not always know the meaning of, but which are also transmitted from generation to generation. This game, shared by a very large number of island women, seems to be as rooted and lavish as other ancestral traditions and constitutes the living fabric of a multifaceted culture.

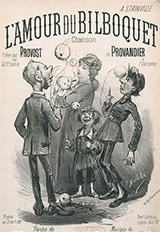

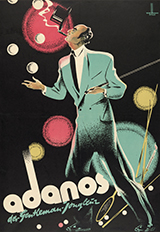

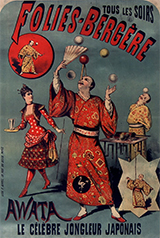

From one continent to another, from one century to another, object manipulation is revealed both as a local, urban or rural practice, associated with a funeral or agrarian rite, but also as a pretext for the creation of works or artistic forms that are out of step with any reality on the ground. This register flourishes particularly through worldly jugglers, dressed in copurchic fashion, a trend that aims to harmonise the silhouette, sometimes by calculating to the nearest millimetre the length of a lapel or the height of a heel. These gentlemen manipulators of canes, hats, billiard balls or crystal glasses and cups, seem to be on their way to or from an evening out and abolish by their appearance the boundary between the ring and the stands. They stand out as a reflection of that era, a projection of a social body that fits well with the last few sparkling moments of a mutating circus. This singular register shone between 1870 and 1910 and faded after the First World War.

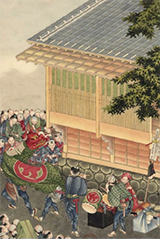

Dexterity in the service of a purpose or experience is also shared by Shinto monks who use object manipulation as a medium for concentration. The practice of Edo Daikagura, a conjuring juggling performed in the name of the Jingu divinity, is the embodiment of a sacred performance gradually transformed into entertainment. Daikagura is one of the forms derived from Kagura, a practice that has its roots in the Heian period. If its "signature" is the shishi mai, the equivalent of the lion's dance for the Chinese, Daikagura also includes juggling and in particular the art of spinning small objects, like a tiny hoop, on an open sun umbrella.

Daikagura has become a street game in Japan, especially during popular festivals, a resurgence of fairground practices that were very popular during the Meiji era and which suggests how much object manipulation in all its forms can be read and appreciated in all latitudes, rooted in societies that value it in often very different ways.