by Pascal Jacob

The term antipodism comes from the ancient Greek ἀντί, anti, against, and πούς, ποδός, poús, podós, foot: literally, to push back with the feet. By extension, the antipodist is therefore the person who juggles with his or her feet, who throws and catches, without hands, objects of all sizes and shapes. It is from this diversity that the originality of the work of the many practitioners who use their feet to push back wheels, spheres, tables, crosses or cubes is born.

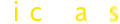

Acknowledged since ancient times, antipodism has everything to do with the sacred, with certain movements simulating the rotations of the sun during celebrations or ritual ceremonies, but virtuosity quickly overrides the symbol and this discipline thrives for entertainment purposes outside temples or plazas. The principle of turning the body upside down to perform "upside down juggling" is particularly fascinating for an audience that is always curious and eager to marvel at agility exercises. The skill of the antipodists surprised the Mesopotamians in the 6th century, enchanted the medieval West from the 10th century and dazzled explorers in the 16th century, a pleasure they reflected in their tales and illustrations as exemplified by Christoph Weiditz, German painter and sculptor who, during a stay at Charles Quint' court, produced a costumes book where he represented Aztec antipodists, faithful to Hernan Cortès' description.

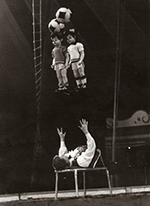

Like many acrobatic and virtuoso disciplines forged since antiquity, developed and popularised in the context of the fair and gradually transformed into acrobatic practices, antipodism became a circus technique and flourished in Europe in the 19th century. The adventure of antipodism coexists with the experience of the Icarian games, two techniques that use the same apparatus. To give the body a proper inclination, antipodists use a trinka, a kind of bench topped by a two-thirds inclination plane that supports the acrobat's kidneys and simplifies body support. Two prominent elements between which the artist's head is placed and against which the shoulders lean, help to steady the back while giving great mobility to the legs. The technical vocabulary is based on the variety and scope of the objects and accessories that are propelled and that fall "naturally" on the antipodist's feet.

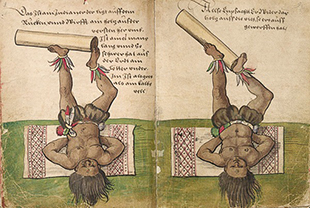

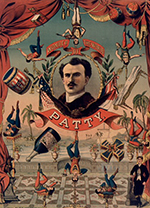

Whether working alone or in groups, depending on the period and culture, antipodism has long and regularly been part of a circus or music-hall programme. At the end of the 19th century, Suzanne Schaeffer, a member of a famous family of icarians, was also a remarkable antipodist, both virtuoso and elegant. In the 20th century, the Roncos, the Myrons, who complicated their work by fixing the trinka at the top of a "held" pole in balance on the feet of a lying base, the Czech Jumgoes who placed a ladder at the end of the base's feet, lying on a miniature car, but also Léo Bassi, Tito Reyes, Josette Romarin or the Kerwich sisters were claiming a joint repertoire, while adapting it to their respective imagination. Thus, Jean-Claude, who "plays" two little footballers, Mick the red and Tony the blue, two dolls he throws with his feet, ironically linking them to the technique of the sport they embody.

Antipodism, a discipline long considered to be largely Western, is also very popular among Chinese troupes founded in the 1950s. Velvet carpets that fly or parasols that fly away and fall back with extraordinary precision at the tip of the foot that propelled them add a level of refinement and preciosity to exercises that have become a bit obsolete in the West. In 1983, the young antipodist Wang Hong amazed the Parisian public by twirling small squares of fabric with diabolical precision. Francis Janacek, Tamara Pouzanova embody a different school, even if the technique obviously remains the same. While Rhodes Dumas remains very conventional in her work with traditional objects, Nata Galkina, a young artist trained at the Lido, Centre des arts du cirque de Toulouse, has created NoGa, a small piece dedicated to antipodism where she plays as much with irony as with flawless virtuosity to manipulate hoops and cylinders, called "cigars" in the industry's jargon. A subtle way of shifting the quality of performance and making it very slightly contemporary.