by Pascal Jacob

The bond is total. The egg yolk, ideally smooth, slides slowly, effortlessly, on Jeanne Mordoj's skin. A flaccid body freed from its shell, its balance is precarious, but the manipulation, light and intuitive, remains a masterpiece. Whether it is balls, hoops, sticks, clay or egg yolk, the technique is always similar to a quest for harmony between a loosened body and the material that approaches it. This mixture of ductility and viscosity is a good symbol of the notions of contact and equilibrium points over the entire body of the juggler. L'Homme de boue by Nathan Israël and Luna Rousseau or the manipulation/creation of clay balls by Jimmy Gonzales play on this fascinating antinomy between bond and detachment.

Virtuosity

The origins of the contact are both ancient and multiple. Burmese chinlon players have been integrating balance games for 1500 years with a wicker ball in punctual contact with different parts of their body. Aztec ball games do not borrow from other sources. The leather ball hits and rolls from chest to shoulders and thus defines the perimeter of play and virtuosity of the winners. The Dane John Holtum or the German Paul Cinquevalli, also considered the first "gentleman juggler", with cane and billiard balls, throw, receive and roll heavy cannonballs on their bodies. The skin and muscles, between ductility and tactility, are just some of the paths used for balls, sticks or clubs as the technology evolves. Over the centuries, jugglers will compete with each other in their creativity to make their work more complex and deliver extraordinary performances where contact matches the controlled imbalance to produce figures that some consider incredible.

If L'Équilibre du verre, a print published at the very beginning of the 19th century based on Carle Vernet's work, offers us a first key to understanding the basics of this discipline, many artists have associated instability and fragility, combining acrobatic exercises and glass manipulation in the same way as the Weldens. Sometimes also, the "pointe à pointe", two opposite swords, one of which is the pretext to put a tray loaded with glasses as illustrated by the Madcaps, the Lanka duo, two Sri Lankan jugglers who balance a pyramid of glasses on a violin bow, the Vietnamese Ngyuen Kuang Minh or the acrobatic equilibrists of the Shanghai acrobatic troupe. With the latter, it must be noted that these games with fragile translucent containers have been fully developed in Asia for several decades.

Xia Ju Hua, nicknamed the Queen of the Bowls Pagoda, opened the ball for the modern West by presenting a memorable act in Europe several times in 1955, where she managed to transform a street game into an extremely refined artistic form. Almost thirty years later, at the 10th edition of the Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain, Dai Wenxia performed in Paris with an extraordinary Pagode des verres ("Glasses Pagoda"). By inserting the banquine technique into the handling of bowls at the feet of the acrobats, the China National Troupe has reached a new level in the fusion of disciplines. Today, most Chinese troupes still have this type of performance in their repertoire, but by international standards, they are the only ones... These acrobatic enchantments, where the extreme physical articulating qualities of the body reveal exceptional balance, were preceded or revisited by several generations of jugglers in the 19th century.

Simplicity

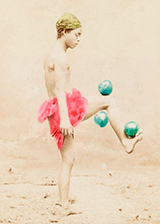

During the following century, strange but nevertheless virtuosic mixtures followed one another and allowed many jugglers to integrate prodigious balances into their repertoire. Enrico Rastelli has marked his time and history by his ability to blend with incredible fluidity the most improbable balances with extraordinary juggling prowess. Whether draped in a sumptuous Japanese kimono or dressed in a silk football outfit, he provoked total amazement at each of his long appearances. Rastelli opened the way for generations of jugglers who, like him, would juxtapose their know-how to create new and spectacular combinations. Paolo Bedini, Piletto, Bob Ripa, Igor Rudenko, Pifar Shang, Massimiliano Truzzi, Gipsy Gruss, Little John, Serge Flash, Rudy Cardenas, Gustave and André Reverhos or Eddy Carello multiply the technical combinations combining ball or hoop manipulation with unstable postures, on a ball, table, wire or pedestal. The Austrian Unus, able to balance on just one finger, is also a remarkable juggler and his act, star of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey circus main ring in the 1950s, is a good symbol of the fusion of the disciplines.

The accumulation of objects and the superposition of effects have long contributed to validate the aesthetics of the discipline and strengthen its technical identity, but an artist like Francis Brunn has totally disrupted the established codes by assuming the purity of the gesture and the transparency of the movement. The body becomes a support and pretext for a sequence in which fluidity is the essential element. A dimension that jugglers like Viktor Kee or Vladislav Kostuchenko enhance by handling simple balls and balloons respectively for a very strong visual writing, but which never alters the precision of the manipulation.

This notion is fundamental in order to understand Michael Moschen's work, based on an obsession with geometry, lines and rhythm, combined with an acute awareness of space. Above all, he highlights the acceptance of a new attitude towards the object. According to him, a juggler manipulates first and foremost millennia-old notions, seizes the void, the hollow or the curve and thus reinvents new spaces of play and virtuosity, Michael Moschen contributed to the first hours of the Big Apple Circus adventure in New York before radically changing the perception of juggling in the 1980s by creating Triangle, a work that is both plastic and juggled that continues to resonate so strongly today.