by Pascal Jacob

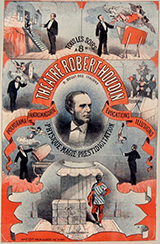

There is sometimes a very fine line between parlour magic and close-up magic, two very similar concepts to illustrate a form of illusion that uses often similar props. During the first half of the 19th century, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin largely contributed to laying the foundations of parlour magic while transposing it onto the stage for his Soirées Fantastiques (“Fantasy Evenings”).

An avid connoisseur of optics and watchmaking, he incorporates machines and automatons into his magic discourses, characters with many talents that he himself creates, such as Le Pâtissier du Palais Royal or the little trapeze artist Antonio Diavolo (1849)1. His shows are elaborated as a succession of attractions with evocative titles. By developing a repertoire of apparitions and disappearances of objects simply borrowed from everyday life, he has paved the way for many practitioners. Cards, scarves, balloons, glasses and canes, but also small animals, from fish to live ducks, constitute a very effective set of tools to amaze an audience whose proximity makes the illusion all the more surprising.

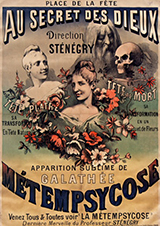

The most notable shift occurs when human partners are systematically involved in the presentation of certain tricks. A form of magic closely linked to the space in which it is practiced, a parlour or a theatre entirely dedicated to it, will be radically transformed when it is presented among other attractions, on stages without any particular layout and require the creation of boxes and accessories that can be adapted to all types of places. The magicians will thus be able to move from a small stage erected in a cabaret to a music hall stage more or less wide or deep. Easy to store and transport, these new magic objects influence the development of a more autonomous magic, simpler to transpose and implement. If the amplitude of the tricks differs, the same magician can nevertheless master several types of repertoires.

1. Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin borrowed the name of his automaton from an aerial rope acrobat who was very popular in the early 19th century, particularly at the Cirque-Olympique in Paris in 1828 and 1829. Cf. Le Corsaire 18 December 1828, p. 2 and 3.