Connections

by Marika Maymard

The modern circus was created in the late 18th century in a crucible of knowledge, disciplines and codes shaped over several millennia. Similarly, modern magic was built on a set of myths, games and scholarly practices which, once ritualised, rubbed up against the lines of sensitive reality. An alchemy was forged between scientific discoveries and raw materials that emerged from an ancestral memory fed into by monsters, ghosts, wizards, satanic charms and divine furies… Such wonders were all described by Pierre Boaistuau in the 16th century in his Histoires mémorables , a curious and terrifying overview that laid the foundations of spectacular illusion.

“If ritual maintains something of its ascendancy over the arts, it is undoubtedly modern magic, a speciality unjustly ignored by contemporary creativity, which bears witness to this with a great deal of force. Magical breathing, cabalistic formulas and pseudo-performative gestures all embody this atavism by creating a veritable ritual semiosis sometimes undertaken without the artist’s knowledge, sometimes deliberately to accompany the achievement of the effect”. Valentine Losseau1

Dreaming of an alchemy

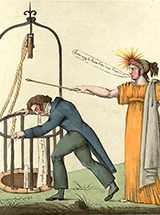

The more the achievements of reason and scholarly observations provided humans with knowledge and a mastery of nature, the more the public sought a confrontation with irrational manifestations and dizzying delights, milestones of the eternal cult of Life and Death. From Robert-Houdin’s salons to the magical theatres of Bénita Anguinet, Loramus, Linski, Delille and Dicksonn; from the vaudeville scenes of Davenport and Maskelyn & Cooke to those of the cabarets, fantastical effects appeared, “borrowed” from Celtic or Egyptian rites, the mysteries of the Middle Ages and Indian spiritualism. Announced and shrouded in mystery by the magician’s patter, they came in different guises, as apparitions, disappearances, transformations and penetrations of the body and objects. “What you are about to see, Gentlemen, is unprecedented and will never be imitated. What you are about to see are wonders, impossibilities, miracles performed at last!” (Robert-Houdin, Comment on devient sorcier, 1868)

Alongside the trend for mesmerism, which spoke seriously of the reality of a “magnetic fluid” in every living being, thaumaturges and other stage miracle workers based their magical powers on the misappropriation of scientific experiments of varying degrees of occult, in the vein of Robertson’s phantasmagoria or the demonstrations with which Louis Comte regaled the princely courts of the First Empire.

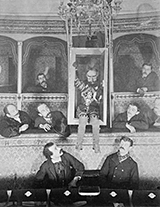

By telling fantastical stories spiced up with effects, modern magic breathed new life into the reign of the pantomime – fairground, equestrian, exotic or “English” – which had been taunting official theatrical productions since the 17th century. Characters from ancient liturgies and mythologies fed into dramaturgy to provoke fear or laughter. This is demonstrated by the “Shows” page from L’Orchestre of 7 June 1891, , strewn with a mishmash of the Sphinx, the Manoir du Diable or the terrible Nain Jaune from the familiar story by Mme d’Aulnay, given a fresh twist by Georges Méliès, new director of the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. The music included a composition by Caroline Chelu on the theme of the Nain Jaune, a Galop brillant pour piano performed by Mme Rehm, while in a specially equipped room, opened at the intermission, mysterious “living and intangible” ghosts appeared.

Mechanical “creatures”

Scientific and technical progress favoured the creation of new wonders and, in particular, the design of sophisticated automatons. Five hundred years after the development by Albert Le Grand2 of a wooden Minerva, servant and soothsayer, in 1879, E. Fétis made history with android machines equipped with bellows that had been reproducing songs or playing music since Antiquity3. Jacques de Vaucanson (1709-1782) created two musical automatons and a digesting duck that reproduced all the phases of the ingestion and processing of food. Around 1770, in his travelling museum, Philip Astley showed Pieces of Mechanism, including his Chronoscope4. But usurpation was not far away and, keen to eclipse the genius of Vaucanson, in 1770 the Austro-Hungarian engineer Von Kempelen exhibited The Mechanical Turk at the Austrian court, an almost unbeatable “chess player”, which, eighty years later, would be unmasked as a fake automaton bedecked with cogs but powered by human intelligence and presence. Paraded across Europe, the clever hoax deceived and defeated its opponents, including Napoleon. In the mid-19th century, Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin devised and staged Antonio Diavolo, the virtuoso trapeze artist, a Pâtissier du Palais-Royal who took orders for sweet treats and served them, or L’Oranger merveilleux which he caused to sprout with flowers and fresh, tasty oranges.

Lights and shadows

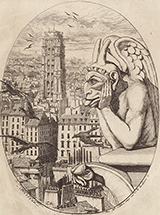

Soliciting the gaze by causing unusual and unexpected visual sensations, the French word for magic, magie, is an anagram of image. Enchanted or abused depending on the proximity, nature or form of the effect, the viewer enters a universe whose unreality can be intoxicating if they let it captivate them. In the 19th century, the golden age of the god of Progress, discoveries in the field of optics and light amazed audiences bewitched by the appearance of black or pallid forms, both familiar and spectral. Coming out of the darkness, characters and sets appeared before a captivated audience. Framed by the surround of a shadow theatre or outlined on the screens of magic lanterns, new heroes, modest and mysterious, now became firmly anchored in the entertainment landscape, from phantasmagoria to the earliest days of cinema.

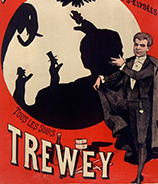

Dominique Séraphin would be the first to present a Chinese shadow theatre5, at Versailles in 1772, followed in 1780 by Philippe Astley, who tried to diversify his “amusements”6. The discipline, known as ombromania, seduced conjurers who practised it in theatres, cabarets and circuses. A century later, Trewey, actor, juggling equilibrist and ombromania enthusiast – and the magician Philippe Beau brought magic and cinema together in their creations. In 1890 Félicien Trevey met Antoine Lumière, with whom he shared a curiosity and wonderment for “the mystery of everyday life”7 and the science of movement, and introduced him to conjuring. In Magie des ombres et autres tours, Philippe Beau put together a show in which magic tricks, living shadows of characters and animals, and brief scenes from films such as tributes to Méliès, Chaplin – Le Cirque (1928) – and Spielberg – E.T. (1982), morphed together in captivating fashion.

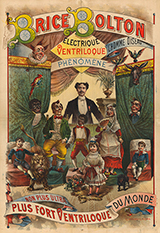

Like long echoes that merge from afar

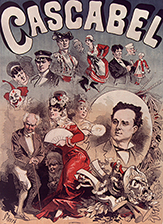

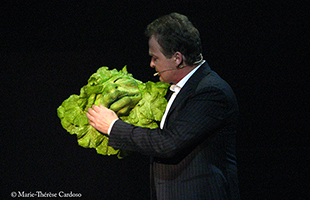

This verse by Baudelaire8 may evoke the legendary resonance of the great voices of the Pythias or other soothsayers through the centuries. Mentioned in the annals of kings, demigods of Antiquity or even in the Bible, as shown by Colombat de l’Isère, the mystery of oracles and incantations, spoken in an intimate setting or in front of a huge crowd, has always been studied. Attributed in Antiquity to a magical process that makes the bowels or even the sexual organs – in the case of the Pythoness of Delphi – speak, the phenomenon was colloquially known as “ventriloquism”. Even in the 21st century, those who artfully master their vocal cords and breathing until they can converse with a double without moving their lips or make characters speak from a distance are called ventriloquists. They usually perform on stage, in the company of a very mobile, charming and nevertheless fiendish puppet in the form of a child, often a bizarre animal or an object – the clothed frog who sings “The cock is dead!”, G. Schlik’s great helm, or even a vegetable, such as Marc Metral’s lettuce. Some artists have more than one “partner”, others change their own character, quickly transforming their appearance and voice, such as the transformist Cascabel who, before Leopoldo Fregoli, ignited crowds and inspired the novelist Jules Verne to create his hero César Cascabel.

Pure entertainment, bristling with provocations, riddled with furtive flashes, to enchant or shock and make people laugh, the two-voice game of the ventriloquist can send a message. In the 1970-80s, Terri Rogers (1937-1999), an English magician (born Ivan Southgate), and her little talkative accomplice Shorty Harris (from Len Insull’s famous studio) promoted the cause of transgendered people9.

Getting stone silhouettes and other idols to talk is a process that serves those with a wide range of intentions. Used as a weapon by Louis Comte, physicist and ventriloquist, who scared off revolutionaries determined to destroy the statues in a church (D’Auberval, 1816), or a memory of Tintin’s explorations, it also reinforced the deadly power of the guru Jo DiMambro over members of the Temple du Soleil sect…and transforms magicians into evil creatures.

The figure of the magician

by Valentine Losseau

In popular culture, the figure of the magician is ambivalent, transposing signs gleaned from the registers of illusionism as well as those of religious, ritual or therapeutic magic. Many 19th century illusionists were inspired by magical phenomena and borrowed from wizards or mages endowed with supernatural powers a connoted gesture: hand movements mimicking telekinetic action, magic wand, "abracadabrantesque" formulas...

One of the most charismatic literary figures in European magic is Doctor Faust. Inspired by a German alchemist who lived at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, this feverish character, full of romantic pride in his quest for omniscience, studies ancient magic with such dedication that he ends up attracting the attention of Mephistopheles, an evil avatar who willingly takes human form. Medieval Catholic Europe had represented the devil as a being with the power of metamorphosis, an enticing and engaging interlocutor, rivalling in intelligence to fool its prey. The Evil One is the master of illusions. Whoever manages to make a deal with him can, in exchange for his soul, benefit from his powers, just as one can, in some Islamic traditions in North Africa, enslave the jinn, subtle and invisible spirits most of the time.

Popularised by Gœthe's work in the 19th century, Faust's success became mythical: Delacroix iillustrated his misadventures with a series of lithographs, Gounod, Berlioz, Sporh wrote their famous eponymous operas. The duo Méphistophélès and Faust inspires the symphonic music of Franz Lizst, Richard Wagner, Robert Schumann, but also literature (Heine, Pouchkine, Tourgueniev), cinema (Méliès, Murnau)...

Arrigo Boïto writes his opera: Mefistofele.

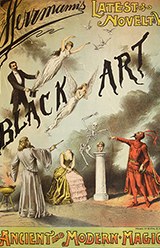

The pact of the scientist and the devil is the knowledge of mortals associated with the impenetrable powers of the universe: together they combine white magic and black magic, real magic and fake magic, secular magic and divine omnipotence. From then on, it is not surprising to find, on the posters of the shows, the portrait of the magician as a doctor, adorned with his supra-terrestrial acolyte in the form of a man dressed in red and wearing a cock's feather (a Mephistopheles stereotype), accompanied by his auxiliaries, clouds of mischievous imps.... From the second half of the 19th century to the 1930s, this imagery became the classic representation of the modern magician, as evidenced by posters by Thurston, Carter, Kellar, Blackstone, Dante, Maskelyne and Devant, Leroy-Talma-Bosco and many others.

1. Valentine Losseau, « Se jouer des esprits. Du rire de Robert-Houdin au rire des indiens Chulupi », in Demeter, "Du rite au jeu" [online], 2016.

2. Monk, scholar, magician and alchemist, Albrecht von Bollstädt, known as Albert Le Grand, was born in around 1190 in Bavaria and died in 1280. Thomas Aquinas was one of his students. “Etiam nos ipsi sumus experti in magicis” (Much more we are experts in magic) he wrote in his De anima, I, 2, 6. 1254-1257 (Paris, Stock, p.32). His Minerva was described by Johannes Trithemius.

3.E. Fétis, “Des Automates musiciens” in the Sunday literary supplement of the Figaro 13 July 1879.

4. Steve Ward, Billy Buttons, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2018, p. 46-48.

5. Alber, Les théâtres d'ombres chinoises, Paris, E. Mazo, 1896.

6. Mike Rendell, Astley’s Circus, 2013, p. 46.

7. Yves Chevaldonné, « "L'homme en morceaux, raccommodé" : de Félicien Trevey au Professor Trewey », in 1895 n° 36 [online], 2002.

8. « Correspondances » by Charles Baudelaire in Les Fleurs du Mal, Spleen et idéal IV, 1857.

9. Also a magician, Terri Rogers invented and developed illusions, for David Copperfield and Paul Daniels among others.