by Frédéric Tabet

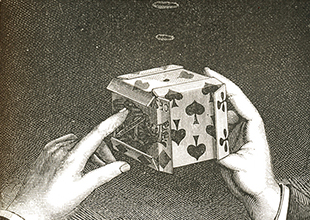

The magician-manipulator generally presents a show most often alone, in evening clothes, in front of the public, without scenery, without apparatus, using coins, cards, cigarettes, but also billiard balls, flowers, scarves, even small animals.

A modern evolution of magic

The etymology of the word manipulator implies a technical conception of the form, which is particularly important since the term is not new. The Latin word manipulus refers to the "handful" of wheat that is held in the hand to sow. Manipulation is the act of holding, of putting into action with the hand. Excluding the meaning of "suspicious manoeuvre", the term is originally used to refer to savants and scientists who carefully handle chemicals and solutions. The term enters the entertainment field through scientific demonstrators. Then it applies to jugglers or puppeteers. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that the magicians took up this title, which the press acknowledged as such.

The introduction of the term and this form of performance coincided with the arrival of foreign magicians in the nascent French music-hall circuit. In particular, it was with tours by American magicians that a genre emerged, first with Nelson Downs in 1900, then with Howard Thurston and Harry Houdini in 1901 and 1902. The expression became commonplace in the first decade of the 20th century and the term quickly spread to all the objects used. Weyer is the "card and flower manipulator", Mr. and Mrs. Servais Leroy present card and coin manipulations, then scarves, Warren Keane is the "card manipulator".

Pure magic?

At first glance, manipulation presents a show that goes back to the sources of presti-digitation in the literal sense of "rapid manipulation". These performances seem to be doubly specialised forms, first of all by the supports used: coins, cards or cigarettes which can form the basis of a show. But also, by the exclusivity of the technical means, when the magician "only" uses the manual skill and dexterity of the fingers. However, this practice, in its early stages, is far from being unanimously accepted. The nascent magic press testifies to the controversies: the manipulators' numbers raise many questions about the place of the technical gesture in the show. Critics of the genre, such as Édouard Raynaly or Prestidigitateur Alber, consider this to be an incomplete, repetitive form of magic that lacks any mystery. Its disciples see it as the quintessence of magic art: a form of pure prestidigitation where there is no need for rigged or hidden props. In any case, the form is developing rapidly because it corresponds perfectly to a new space of representation.

Music-hall magic

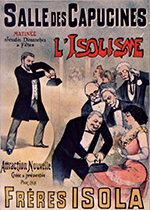

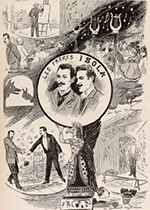

In the early years of the 20th century, the music hall established itself in France, notably under the impetus of former prestidigitators, the brothers Isola, Émile (1860-1945) and Vincent (1862-1947). In this "formidable chaos" described by Gustave Fréjaville, the numbers quickly followed one another. The focus is on the clash of attractions rather than harmonious continuity. For artists, the preliminary installations must be done quickly. The short, often silent and relatively static manipulation numbers are therefore perfectly adapted and are firmly established in music hall programmes.

A competitive number

The manipulation continues, particularly under the influence of competitions. By forming unions and associations, particularly around magazines, magician artists seek to defend their art against fraudulent practices and unveiling, as well as to distinguish some of their members. In the first issue of the trade journal L'Illusionniste, in 1902, the management announced the creation of a competition that would allow "readers and subscribers" to give "free rein to their imagination and ingenuity". In 1909, manipulation became an award-winning category. Competitions seek to stimulate creation, but also to evaluate and rank competitors. They segment the magic art by establishing categories and generate a search for virtuosity. The success and persistence of the manipulation numbers are part of this perspective, because even if a spectator is not totally under the illusion, "the expert connoisseur [...] understands and appreciates the difficulty". This form always seduces magicians who admire the virtuosity of their peers.