by Thibaut Rioult

Linked to the development of parlours and prestidigitation theatres, parlour magic was historically marked during the 19th century by its association with fun physics and manufacturers of illusionist devices. In the 20th century, despite the permanence of the expression "parlour magic" in the vocabulary of illusionists, it remained difficult to define following the disappearance of these components. Between close-up and stage magic, its format is hybrid and uncertain.

The stage, the repertoire and the audience : to new locations

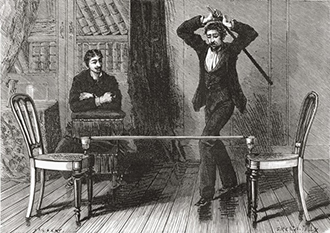

Parlour magic can be characterised by its scenic space, its repertoire, including its props, and its interactions with the public. The notion of "parlour", above all, induces a distance of social interaction of a few meters. This distance corresponds globally to the "social" distance described by the proxemics theorist Edward T. Hall [The hidden dimension, Paris, 1971], the close-up relating then to the "personal" distance and the stage to the "public" distance. Unlike the close-up, the magician therefore has his own space, his own stage, where he usually works standing up. The repertoire involves everyday objects but also props specific to the world of illusionism (cups, rings, scarves... as well as prestidigitation devices (boxes, tubes... variously rigged), but it will leave out the great illusions. Finally, the proximity to the audience – the intimacy of the parlour – allows for an interaction that, while less intense than during a close-up session, is no less important. Micro magic had made the fourth wall disappear. Within the parlour magic framework, there remains only one porous border that the artist crosses at leisure. Thus delimited, social magic, cabaret magic, street magic and fantastic illusionism are the modern extensions of 19th century parlour magic.

Leaving theatres and parlour magic, magic is now inviting itself to private households. The 1930s were marked by the publication of several books intended for the general public, which caused some turmoil among professional associations. There is an outcry over the revelation of tricks to non-magicians, while this diffusion accompanies the emergence of a generation of enlightened amateurs who will promote prestidigitation in France. These "recreations" or "board tricks" are mysterious amusements that can take place at the end of meals, in the living room, in the garden, to entertain, laugh or be amazed. Magic changes location: here we go from parlour magic to magic in your living room!

Parlour magic also finds a privileged field of expression in cabarets, cafés-theatres and music halls. With limited equipment, magician artists such as Jean Merlin, Otto Wessely, Jan Madd or Gaëtan Bloom would then present short, generally funny and exuberant numbers. But cabaret magic requires the magician to perform a number that is immediately proven, immediately "profitable". It is difficult then to perfect a number and in this context the magician artist who fails to win over the audience for an evening does not have a second chance in the same place.

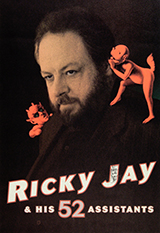

Some artists work in their own particular settings. As an inventor and merchant of close-up tricks, Dominique Duvivier regularly presents shows at Le Double Fond, opened in Paris in 1988, in a format close to parlour magic. The most common scenic device to succeed in this intermediate form is to place two spectators at the side of the magician, facing the room. The spectators delegate their representatives in a way, privileged witnesses and guarantors of the "honesty" of the magician, whom Ricky Jay calls the "eyes of the public".

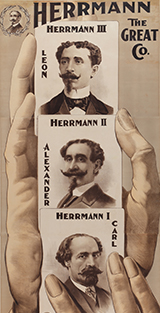

This stage layout is nothing new since it is already used by the first generation of American close-up masters. A wonderful patter merchant and manipulator, the American Ricky Jay brings magic to the stage of the Second Stage Theatre on Broadway, in New York, in 1994, with his show Ricky Jay and His 52 Assistants. In an intimate setting, in direct contact with the spectators, Jay brings his... 52 cards into play, which he uses as aids to mix tricks, the history of illusionism, demonstrations of cheating and card throwing. In his hands, the cup trick, renamed for the occasion "The History lesson", is a pretext for a historical retrospective of the different types of utensils used for this trick.

Permanence and ephemerality: life of the repertoires

Illusionism has its roots in the mists of history and relentlessly revisits immortal objects such as cups, coins, strings, cards or rings. The parlour magic repertoire encourages the use of these props, which are neither completely banal nor completely artificial, and it is in this in-between that magic is born because, if these props are timeless, it is mainly because they appear as symbols. The engineer and clown magician Mimosa (1960-) notes that it is by making pure white doves appear that the manipulator Channing Pollock (1926- 2006) achieves immediate success, while the coloured doves seem to be more inconspicuous.

Perfectly adapted to the format of the parlour, the magic cup game in its many variations is one of these "immortal tricks". In the 1970s, the Egyptian Luxor Gali Gali (1902-1984) ended his act with the apparition of a multitude of chicks in place of the usual fruits. The British street artist Gazzo (1960-), on the other hand, chose to take a melon out of his bowler hat. The American Alex Elmsley (1929-2006) finishes his routine with cups filled with sand that comes out of nowhere. The Frenchman Jean Merlin (1944-), after a frenetic succession of apparitions, finished with fifteen cups on his table. The Belgian Christian Chelman (1957-) offers a unique routine with a cup that is full. The Dutchman Tommy Wonder (1953-2006) built his act around surprises such as the apparition as a running-gag, as untimely as it is inexplicable, of the pompom of the bag containing the cups. Each artist models the trick according to his or her sensitivity and creativity. Thus, the American Jason Latimer (1981-) won the 2004 close-up, inventiveness and FISM championship Grand Prix awards, with a breath-taking number of translucent cups where the nutmeg appeared and disappeared on sight. In a very different register Gaëtan Bloom (1953-), tackles the myth by developing a parodic explanation and skilfully manipulating a hair dryer! And the story of the cups continues to be written, with an alert wand, gesture after gesture.

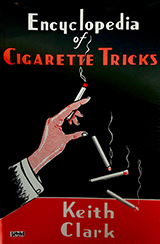

On the other hand, there are "deadly" objects that cross the century at meteoric speed. This is the case with cigarettes. In his writings of the 1930s, the magician John Northern Hilliard (1872-1935) described this branch of magic as one of the greatest advances in prestidigitation, even going so far as to regret that it sometimes eclipses traditional disciplines such as the manipulation of coins and other objects. In the space of twenty years, the numbers multiplied under the impulse of artists such as the Englishman Cardini (1895-1973). In evening wear, top form and monocle, in vaudeville or cabarets, he stands out for his appearance and his ability to manipulate cards, billiard balls and cigarettes in white gloves... Gloves that, as a young British Army recruit during World War I, he had to put on and keep for training in the freezing cold of the trenches. The Frenchman Keith Clark (1908-1979) presented a cigarettes number at the Moulin Rouge and published an Encyclopaedia of Cigarette Tricks (1937), translated a few years later into French (1953), then Celebrated Cigarettes (1943). It is the time when tobacco was socially valued, especially in the cinema. A few decades later, systems such as those in France under the Evin Act in 1991 caused the practice to become increasingly rare in Europe. This inspires contemporary artists, such as the mime magician Kaki or the inventor of tricks Alain de Moyencourt (1954-), to stage attempts to wean themselves off with many magical twists and turns. Linked to the social conditions of the experience, magic adapts to everyday life and re-enchants it again. It allows us to reclaim reality.

« Do it real ! »1 : bizarre magic and fantastic illusionism

At the end of the 1960s, the protest was widespread. Not a discipline, not a field of knowledge that is not spared by a groundswell that challenges traditional models. Prestidigitation is no exception. Bizarre magick (bizarre magic) appears in the parlours, draped in mystery. The English artists Tony Shiels (1938-) and Charles Cameron (1927-2001) revive myths and legends – including those of witchcraft – or great fantastic figures like Dracula, Sherlock Holmes or Nessie. The 1960s were indeed the ideal time for this outbreak: the birth of fantastic realism, the intensification of paranormal research – more or less scientific – but also the golden age of new age currents such as the neo-witchcraft Wicca, the neo-Pagan religion that Gerald Gardner founded in the 1950s, by extending the work of the occultist Crowley.

Across the Atlantic, this call is heard by illusionists such as Tony Andruzzi2 (Timothy Mc Guire 1925-1991) or Tony Raven (1930-2005), who see it as a way of breaking with the dead ends of classical illusionism and its rigidification. Attempting to reconnect with the roots of magic, bizarre magic seeks to bring to life the original and brutal experience of the sacred. Mysterium tremendum, a terrifying mystery, as the German theologian Rudolph Otto described it at the beginning of the century. For the "bizarrists", it is a question of rethinking in depth the role of the magician, the magical atmosphere and the presentation of the tricks. If these remain parlour tricks, it is their theatricalisation that will take them to another status and give them meaning. The objective remains to entertain the spectator, certainly, but by frightening him, by challenging his beliefs and by finishing to erase the fragile frontier between this world and the other... Bizarre magic is nothing more than "magic made like magic"3.

This quest for realism leads to the work of Christian Chelman. He creates an unprecedented qualitative breakthrough by using authentic objects, from different magical traditions, as supports for his routines. The bizarre magic becomes fantastic illusionism. Claiming to be part of magical realism, Chelman followed in the footsteps of authors such as Jean Ray and Thomas Owen and set out to reconstruct and stage the origin of modern myths (vampires, fairies, lycanthropes, superheroes, etc.). His work takes the form of a collection of magical objects that can be "activated", visible either at the Surnateum, a private museum in Brussels, or during exhibitions (notably Persona at Quai Branly in 2016). Finally, close-up and fantastic illusionism cross over: one enchants objects from life, the other brings enchanted objects back to life.

Outside the walls: street magic

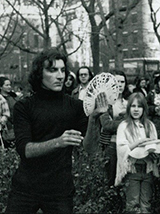

Street magic is the extension of parlour magic in its traditional, non-televised form. It takes up the three proposed specificities. Practiced standing up, it symbolically delimits a scenic space with a rope on the ground, hats, children sitting in the front row, or any other easily recognisable marker. The difficulty in attracting the attention of passers-by, in transforming them into a captive audience, then ultimately into generous donors, makes it a form of magic that is often spoken. Spoken, or rather, addressed to the public. Thus, the street magic professional Jeff Sheridan (1948-) successfully performed a completely silent act for years (late 1960-70) in Central Park in New York and, later, at the Georges-Pompidou Centre in Paris. The absence of speech is not the absence of communication, quite the contrary, his number is extremely interactive. Sheridan uses gesture, mimicked as a universal language. Around a street festival in France, Professor Rognolet can be seen in the position of the street vendor patter merchant and charlatan, a seller of theriac and orpiment powder, whose effectiveness he proves with great illusion.

In conclusion, based on a place that disappeared historically in the 19th century, "parlour magic" is a fuzzy category that has become difficult to use. Just as its repertoire has evolved over time, could we not simply transpose the expression "parlour magic" into "social magic"? The notion would better reflect the social interactions that characterise it today, by choosing the dynamic structure rather than the place as the main criterion.

1. Bizarre magick as defined by Tony Andruzzi, quoted by Eugen Burger in Strange Ceremonies: Bizarre Magick for the modern conjuror, USA, Kaufman and Company, 1991.

2. Also known as Tom Palmer, Masklyn ye Mage or Daemon Ecks.

3. “Magic done as magic”: bizarre magick as defined by Philip Willmarth.