by Pascal Jacob

The use of weapons or projectiles very quickly represented an interesting source of inspiration for many jugglers from the origins of the discipline since medieval illuminations already represent small silhouettes that handle daggers. Swords, sabres, yatagans, axes, spears, knives or hammers are thrown, manipulated, rotated or tossed around a still body in front of a wooden plank. The attraction of danger is an irresistible magnet for audiences always hungry for thrills. A duo of Chinese manipulators from Laocheng has taken over the ritual juggling of heavy tridents, with this curious innovation: the man moves on the heads of six high wooden logs while around his body twirl up to five tinkling spears.

The possibility of juggling with sharp instruments has fascinated the public since the dawn of humanity: why not imagine one of our first ancestors handling finely carved flints in front of the amazed members of his tribe? The use of boomerang, a specialty revisited by the sisters Tilly and Dolly Price around 1910, does not draw from other sources: throwing, catching. Or killing. Ballistic manipulation has become spectacular and is flourishing on the music hall and cabaret stages as well as in many circuses around the world.

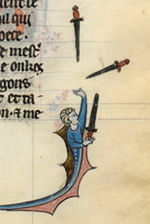

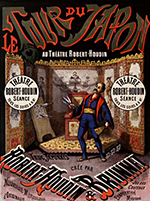

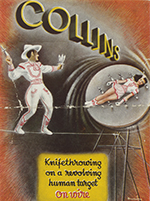

Associated with an exotic practice, projectile throws are sometimes presented in a very naive way, such as in an engraving from the 1860s by the lithographer Hoster, which shows knife throwers wearing loincloths and the chief wearing feather caps, a look that is not unlike Tou-Tainsko on a poster from 1890. The "Wild West Games" also offer a number of opportunities for the implementation of a singular repertoire where daggers and tomahawks take... the lion's share! Kitted out as cowboys or Indians, the practitioners of these very particular disciplines sometimes complicate their exercises by performing them, like Henri Maîtrejean at the Cirque Napoléon, the Tornados or the Collins, on a wire. In addition, the circular structure used to attach the human target is rotating slowly but steadily.

The notion of risk that characterises all these practices is a sensitive marker for several contemporary companies wishing to question this logic of appreciation of prowess. With Marathon and Risque Zéro, two shows created under the colours of the Galapiats, Sébastien Wojdan plays on the concern raised by the proximity of the audience confronted with danger... under control. If the knives thrown and stuck around the artist inevitably cause shivers, it is when a target for an archery sequence is placed between two sections of stands, therefore surrounded by spectators, that the uncertainty can be seen on the faces. The handling of one or more axes causes the same anguish, probably because it is a worrying weapon, linked to ancestral fears. For Timber!, a Cirque Alfonse show staged by Alain Francœur in 2010, all the tools of the lumberjack are called upon to scare the audience. Tow hooks, long saw cutters, whip and, of course, axes play their scary role in the hands of those who handle them.

One of the acrobats of L'Enfant Qui, a show by Patrick Massé at the Théâtre d'un Jour, rotates a heavy mace close to the eyes of the spectators around him and thus summons the spirit of the local juggler while exploiting the delicate interplay between fears and anguishes. Bert and Fred use this ambivalent game with the emotions of the audience with a lot of humour to create short sequences where one character victimises the other with darts, daggers, hammers or whips to the delight of the audience, who see a cathartic dimension to their own desires mixed with a sense of fear. Finally, Johann the Guillerm manipulates a meat cleaver in Secret, a suspenseful moment in the show where the dilation of time takes on its full meaning: if the cleaver does not stick in the block, the artist repeats his gesture, until it is completed, whether he has to do it again 5, 10 or 30 times…

A spectacular and popular practice, blade throwing inspired sculptor Alexandre Calder to create one of his Circus' humorous sequences, developed from 1926 onwards. The painter Henri Matisse also entitled one of the illustrations in the book Jazz published in 1947 Le lanceur de Couteaux ("The Knife Thrower"). This practice has finally led to the creation of companies and associations such as Eurothrowers or the Ligue des lanceurs de couteaux et de haches ("League of Knife Throwers and Axe Throwers"), which bring together thousands of practitioners around the world. Thus, whether pictorial, symbolic or real, ballistic manipulation continues to disturb, fascinate and inspire spectators and designers alike.