by Pascal Jacob

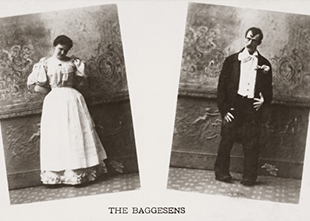

A first plate crashes before arriving at the table nicely set up for a lunch or dinner that will not take place... In a few minutes, whole and unstable piles will collapse with a formidable consistency. Then will come dishes and soup tureens, carefully reduced to pieces until the curtain falls, almost out of mercy, some chroniclers will say, to give the audience time to catch their breath and to give Baggessen, the juggler whose skill is expressed in the opposite way to all his other colleagues, the chance to reap the acclaim…

Spinning plates

Skillful manipulation is a counterpoint to the virtuosity of juggling, but here too the supports reveal themselves over time in an infinite variety. Taking everyday objects to transcend their use, playing with instruments related to hunting, games or sports such as Picaso father and son with ping-pong balls or Serge Percelly and his tennis rackets, adds to a repertoire of styles and stimulates amazement or surprise. Spinning plates with thin bamboo sticks is a thousand-year-old discipline, born and developed in Asia, but which many entertainers in the West have chosen to embrace. While plate manipulation in China is more of a female discipline when it is "serious" and elegant, it can be interpreted by men when it takes on a comic dimension. Dressed as cooks, North Korean artists do pretty much the same thing, mimicking surprise and horror as they spin more and more plates on rows of bamboos stuck in long tables or consoles.

Sport and games

The catalogue of objects used as pretexts for the development of games of skill is sometimes surprising. If the glass pyramids, up to a hundred in crystal manipulated by Wolfgang Bartschelly in the 1960s, a virtuoso reference to Chinese "pagodas", but with a very different energy and especially a form of urgency in the sequence of figures, may seem classic, it is not quite the same for Vincent de Lavénère's chistera, Ezech le Floch's bilboquet, Zoomadanke's Kendama or Koma Zuru's spinning tops in the 1980s and Ba Jiang Ho's today. These "small" objects, from sports or games, have become beautiful pretexts for the development of new disciplines.

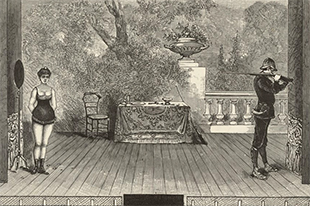

The use of weapons, from the crossbow bolt to the feathered arrow, offers spectacular possibilities, but in some cases it also makes it possible to play with a feeling of anxiety among the spectators. When Guy Tell performed with his crossbows on the Barnum's Kaleidoscape ring in 1999, the men at the gate installed glass screens all around the ring in seconds to protect the audience from a lost bolt. To perform the highlight of the act, Guy Tell stood in front of the curtain, his back against a wooden board, an apple on the top of his head. He would shoot a bolt at a first crossbow and thus trigger a second bolt, which in turn triggered a third bolt, which in turn triggered a fourth bolt until the sixth bolt came and went flying into the fruit on the shooter's head... All this obviously taking only a few seconds. The most unpleasant aspect, according to the artist, was the equivalent of the half-glass of apple juice that flowed down his neck after the impact! Archery with the feet is a Mongolian specialty, implicitly linked to the practice of contortion, also controlled by an acrobat like Elayne Kramer who makes it the final element in her act. Enkhtsetseg Lodoi, an outstanding contortionist and the first Mongolian artist to have performed in the West, created an amazing act in 2017 with nine artists for an impressive collective shooting sequence where the targets were sometimes moving. This discipline is also part of the repertoire of the Inner Mongolia Acrobatic Troupe and is performed alternately by men and women.

Hats, etc.

The manipulation of hats is an ancestral technique in Asia, very widely used by Chinese troops where it is considered to be resolutely collective. The numbers are invariably constructed on an entrée sequence with a group of ten, twelve, fourteen or twenty people, a succession of individual prowess and again a sequence of collective figures before a final throw of dozens of hats to the sky. The Song Trang show, created in Hanover in November 2018 by a company founded by Vietnamese artists, offers a collective number of hat manipulation based on the same technique but with subtle differences in the construction and sequencing of the figures. The technique is sometimes embodied by Western jugglers, exceptional soloists like Bela Kremo, a virtuoso of hat manipulation for a number written to the second and first presented in Sweden in 1931. Béla Kremo added her son Kris from 1970 to 1976 to the group for a spectacular duo where the two men drew beautiful effects from their mirrored juggling. In 1995, for Le Cri du Caméléon, the choreographer and director Josef Nadj imagined a sequence of hat manipulation, underpinned by a surrealist aesthetic and a lot of humour in the very fluid structure of the sequences.

Kris Kremo has kept the trilogy of objects used by his father, as Peter Woodrow did in 1950: rubber or pool balls, hats and cigar boxes. This third "accessory", simple wooden blocks in reality, is sometimes the reason for an entire number, like the one created by Eric Bates. His exceptional technical mastery enables him to build multiple variations, including a part in interaction with the audience that renews the perception of prowess. Trained at The Kiev Municipal Academy of Variety and Circus Arts, Valeriya Dolinych has created a remarkable manipulation act with a single cane, a mixture of ground acrobatics and juggling that opens up new perspectives. The game of meteors, two small cups connected by a wire and filled with embers that sparkle thanks to the impulse given by the manipulation with the feet or the hands, is implicitly reminiscent of South American bolas. Originally a hunting or war weapon mastered by the Incas and which made them invincible until the arrival of the conquistadors, the bolas became a pretext for a sonic manipulation, made popular by Argentine troops in particular. The batons and sticks specialists flourished in the 19th century and the technique of the devil's stick and the twirling stick spectacularly embodied by Nathalie Enterline, both dissimilar and complementary, seem to belong to this intuitive lineage that is part of this inexhaustible register of games of skill.