by Pascal Jacob

When jumping, leaping or springing up, the energy condensed so that a body might lift itself off the ground is fascinating. And desirable. Being capable of crossing an abyss, or conquering the void, is a very human obsession. Early solutions were mythological and magical in nature. Seven league boots appeared for the first time in Charles Perrault's (1628-1703) fairy tale, Sleeping Beauty and became very popular with the tale of Tom Thumb, by the same author, in which they play a far more central role. These magic boots enable their wearer to jump long distances, in the mythological tradition of Perseus' sandals, Mercury's winged heels and Loki's shoes – the Nordic god of discord.

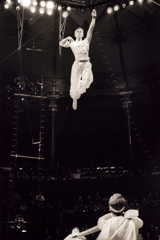

The idea of raising oneself up, mainly over a wall, was an early incentive for the principle of propulsion. The use of a thin tree trunk, sufficiently flexible to create a rebound effect, such as elm for example, was the prelude to the Russian bar. A popular game in Russia, it was played at village fairs before gradually developing into an original discipline, which was adopted by the circus and developed both acrobatically and technologically. The first Russian bar companies were faithful to the original spirit of the game and developed their exercises on a simple, flexible wooden cylinder. Beyond the material, it was the narrow width of the support that rendered the performance spectacular. Acrobats such as the Chemchours dazzled audiences by performing on simple bars carried on the shoulder of a vigilant partner. The bars were gradually made wider to enable more complex figures. They were also made more flexible with the use of fibreglass, and enabled somersaults to be performed in ever-higher numbers. A current Russian bar can propel an acrobat eight metres into the air. This rebound energy is found in the ancient practice of cuerda dinamica, a technique developed mostly in Colombia, where it was similar to a street game, and where it gradually transformed into an acrobatic technique. The rope artist José Henry Caycedo, trained at the Fratellini Academy, presented this form, which is rare in the West, at the 29th Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain. The discipline has elements of the slackline, a contemporary rope dance practised freely using a simple flat strap stretched between two trees.

Origins and references

The origins of propulsion are clear: raising oneself towards the sky, taking flight, attempting to move closer to the birds, the sun and Icarus, is a temptation shared by all. Nalukataq is a major spring festival for North Alaskan Inuits, celebrating the return of the whalers. It is characterised by an abundance of food and a traditional game, in which men and women of the community propel dancers and volunteers into the air, using a wooden structure covered with a taut patchwork of walrus skins, which can be either square or round. This ancestral practice also evokes a tapestry by Francisco Goya created in 1791-1792, named El Pelele. In the tapestry, a puppet is propelled into the air using a sheet stretched out by four elegantly dressed young women. The use of a surface made flexible by tension placed at its edges was a prelude to the trampoline, an apparatus that borrows as much from the propulsion principle of the springboard, as it does from that of an animal skin or canvas stretched over a frame. The material itself is not elastic, but the springs that attach it to the frame develop the necessary energy to distort the original.

On February 14th 1843, a certain Henderson, a trick rider and acrobat starring in Pablo’s Fanque Circus Royal, might be one of the first trampoline artists identified in a circus ring, although it would seem the apparatus was more of a long trampoline than a trampoline as we know it.

In 1887, the American, Thomas F. Browder, developed the safety net, a circular and opaque tarpaulin stretched over a metal hoop, used by firemen to catch victims who sometimes had no choice but to jump from a window or a roof to escape toxic fumes.

The circus legend credits a certain Monsieur du Trampolin, an artist who supposedly had the idea of making the most of the natural rebound from the protection net used by trapeze artists to develop a new act inspired by the elastic element of the material. It was in fact in 1936, that George Nissen and Larry Griswold, two gymnasts also inspired by the flexibility of this safety net, invented the trampoline, an apparatus promised a fine career in the sporting domain and, more episodically, in entertainment. Ray Dondy, a popular 1970s acrobat, became famous for his character of a bather mistreated by his trampoline, which evoked a swimming pool. In the 1990s, the Blue Brothers trampoline champions created a highly dynamic act based on their exceptional technique.

Ever further…

Soaring up, gaining speed, and pushing off a "cushion" or a small springboard to jump onto a galloping horse was common practice on the 19th century. This simple propulsion idea to support the trick riders' efforts was similar to the technique developed by Archangelo Tuccaro in his Trois Dialogues dans l’Art de Sauter et de Voltiger en l’Air (Three dialogues in the art of jumping and performing acrobatics in the air), published in Paris in 1599. With numerous illustrations, he describes this little springboard that enables easy flight and acrobatics, such as passing through large hoops held at an equal distance by a dozen people. This jumping register was fully explored with the batoude, a trampoline several metres long set up between the walls of the mounter, and which stretched back behind the scenes, enabling acrobats to build up speed and soar into the ring performing a series of increasingly complex jumps. Batoude jumping, a highly fashionable discipline in the 19th century, comes from the Italian Battuta, from the verb battere, "to beat." It describes both the "kick-off of a ball" as well as surface of the beaten earth floor on which the kick-off is given. It is fine grounds for organising daily jumping contests in which the acrobats are all as skilful as each other, and multiply the obstacles to win a symbolic reward and enjoy reading a few lines about themselves in the local press. Sometimes a platoon of soldiers is called upon, armed for war, with bayonets fixed, to constitute a human rampart placed in the axis of the batoude, that the jumper clears with a leap, while the crossed guns fire a salute with blanks, filling the circus with noise and smoke. Jean-Baptiste Auriol, an exceptional acrobat, is a specialist at this type of jump, immortalized by the painter and illustrator Victor Adam. Elsewhere, horses or camels are lined up, while in the United States, elephants are preferred to create an ephemeral moving grey wall. In 2006, the Fratellini Academy put on a large batoude act, setting the apparatus at the same incline as that of the tiered seats. Part of the Knie, Swiss circus programme, the act presented at the Cirque d’Hiver for the 27th Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain, led to better comprehension of the impact of these acrobatic exercises on the audience, carried away by the energy and power of the acrobats. The propulsion principle, a mechanical amplification of the human capacity to jump, draws both on war sources and entertainment: in 2008, Laurent Gachet created Dédale, a remarkable show developed from the Labyrinth myth and for which he created a dizzying sequence in which acrobats were propelled by a gigantic ram, tied to a nine metre-high tower.

Half game, half combat, the jumps established a spectacular duality that actually characterises the entire history of the circus rather well.