by Magali Sizorn

Offering a variety of possibilities on a suspended bar, the Washington trapeze is a mobile balance apparatus that evokes the hypotheses of a fall in a game of vertigo, rather than acrobatic flying.

On the wire

The second half of the 19th century was one of innovation and a race to create exploits in a circus context that was fun, thrilling and exciting. Jules Léotard (1838-1870) added hanging and flying, while Keyes Washington (1830-1882) gave his name to the balance trapeze. By widening the bar in the middle and making the apparatus heavier, he introduced other uses for the trapeze apart from those stemming from gymnasiums, which were then developed by aerial acrobats. Working on a trapeze, "Washington style," meant using the bar as a wire, evoking the exercises performed by ropedancers and tightrope walkers.

Defying falling

In Les jeux du cirque (1889), Hugues le Roux tells how he admires an act by the young Italian, Erminia Chelli, composed of an "increasingly difficult ascension," including balancing upright on a globe, itself set on the trapeze bar (Le Roux, 1889: 177-178). The show thereby evokes a blend of ilinx (Caillois, 1958), and maximalist technical feats, combining elevation and fall with balance and imbalance.

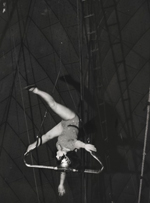

Washington's successors would in fact complicate his technique, braving imbalance by standing, kneeling or performing headstands on the bar. In the 1950s and 1960s, Pinito del Oro thrilled audiences by performing balancing acts on one knee or standing on the swinging, swaying trapeze with neither safety wire nor net. This star of the ring published a book dedicated to the discipline (Del Oro, 1967). At the same time, the German, Lothar, managed to achieve the famous swinging headstand, which has become the highlight of Washington trapeze acts. Brothers Eugenio and Renzo Larible positioned themselves one above the other on immobile trapezes to carry out various acts such as lifts, rotations, headstands, juggling rings and so on. This combination of balancing and juggling can be found in many acts developing performance and skill, such as that of Uwe Neitzel, bronze medallist at the 1990 Festival mondial du cirque de demain, and those of several Soviet duos in the 1980s. These duos placed the classical conventions of the Washington trapeze in aerial ballets, combining balance trapeze, juggling and choreography (Hamel, 1989).

The Frenchman, Gérard Edon, originally known under the pseudonym Silky, added an additional level of danger. Standing, facing forward on his trapeze, it was impossible for him to catch hold or to use his arms to balance himself. This forward facing swinging was to be his glory, and he was rewarded in 1982 with the National Grand Prix Circus prize. Hours of rehearsal were needed to perfect this highly risky act. Being a trapeze artist "is not improvisation," he said. You need to "overcome your apprehension" by rehearsing and by permanently looking after your material, so that every evening you can work "with the void."1.

Above the abyss

If balance trapeze acts are a relatively rare speciality today, contemporary creations honour this spectacular apparatus, which is still the measure of what separates the ground from the air, and the earth from the sky. They also use its metaphoric potential which lies somewhere between a pendulum and a swing. The suspended wardrobe comes to mind, beating time in Bal Caustique by Cirque Hirsute (2006). Or the artists crossing the ring, taking turns to jump over a trapeze swinging low across the ground in Cirk 13 (2001), the CNAC 2001 graduation show directed by Philippe Decouflé. Sebastien Dault, a graduate of the 2001 Cnac class, reconsidered his relationship to the Washington trapeze in Bougez pas bouger (2002) by the Oki Haiku Dan company. Against a streamlined stage design, and with the La Main d'Oeuvres company, he plays with the confines of balance and fall, on improbable apparatus that provide more unexpected images than the apparatus he trained for.

Keyes Washington's trapeze is in fact no longer necessarily at the forefront, and from now on, humans suspended above the abyss experiment with the void and vertigo by blending the possible uses of the trapeze (balance, fixed, swinging) with adjustments proposed by newly invented apparatus and other objects to explore.

Interview

1. Interview with Gérard Edon in July 2004.