by Pascal Jacob

The horizontal and vertical axes encompass all the constraints for aerial acrobatics, creating a framework of norms for a performance or an intention. The space above the ring was for a long time allotted only to trapeze artists, the emblematic figures of an artistic device largely anchored in the ground, and often limited by the architecture of the performance space. The boom in the flying trapeze, a technique that saw distances between two points covered using figures and rotations, led to another means of conquering this space in an innovative and intuitive manner from the late 19th century onward.

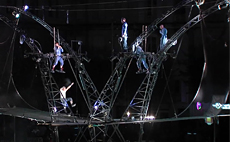

The implementation of another spatial approach to the circus, the choice of mono-disciplinarity from the 1990s, access to a multitude of playgrounds with changing constraints, and the redefinition of verticality, largely allotted to the corde lisse alone, have, for more than twenty-five years, provoked the development of a new branch of disciplines, which was inspired by sometimes obsolete forms, or those which were trapped by a conventional viewpoint. Les ombres de la nuit, La Fiancée d’Igor, La Sœur d’Icare s’appelle Illusion as well as Orfeu, Kayassine and Ola Kala, shows created respectively by Tout Fou to Fly and the Arts Sauts companies, founded in 1993, developed a new approach to aerial disciplines as seen in Epicycle by the VOST company, or Hallali and the 5e de Beethov’ by the Philébulistes.

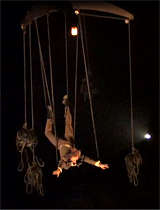

It was a story of emancipation, independence, and freedom. It was a call for air by several generations of acrobats who were curious about taking on a vocabulary with which to compose new legends. By creating Frequent Flyers Productions in 1988, Nancy Smith opened the way for a different style of aerial arts in North America, combining suspended bodies and choreography, in a perception of the void that corresponded well to research by Clémence Coconier, which was developed and conveyed in Mue. It also corresponded to creations by the Moglice-Von Verx company, co-founded by Chloé Moglia and Mélissa Von Vépy, such as Un Certain endroit du ventre, in which the trapeze is simultaneously an object of desire, of discord and of reconciliation, and I look up, I look down, haunted by the verticality of a steep wall. The company, which is now Happés théâtre vertical, questions oscillation, suspension, and imbalance in Miroir, Miroir, Croc and VieLLeicht performed by Mélissa Von Vépy.

Risk taking

The empty space above the ring beneath the big top cupola or the flies in a theatre, bound by a canvas or the sky, lends itself to aerial proposals detached from all references other than simple adaptation in a restrictive setting. For some people, it's a radical approach. The Retouramont company uses vertical dance to explore another perception of urban space, through polymorphous research that feeds on the ruggedness of architecture, its textures and flaws. In Les ondes gravitationnelles and Clairière urbaine, Fabrice Guillot invents another rapport with the void and the city, detaching the immobile surface of the wall by using lights and the movements of his acrobat-dancers. From the whole city as a space for performance and experimentation to the intimacy of a sunny courtyard, it is just one nimble sidestep, which Chloé Moglia chose to take with Le Vertige, a literary and aerial piece in which the unbalanced body illustrates a fear of the void emphasized by ruthless words.

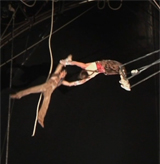

The Void: a dimension that Fragan Gehlker inhabits with humour and skill by questioning the myth of Sisyphus. From a forest of ropes with unstable fixations, he draws material for prodigious climbs, dizzying falls and a salutary questioning of the risk taken, with and around an apparatus that was, for a long time, intended to hold the audience's attention while the central cage was taken down. It is all about breaking down the framework and stereotypes that follow the history of these suspended objects, and developing another philosophy of the void, the fall, and flight, by playing with an apparatus that no longer necessarily goes by its name. Part insolence, part strangeness, and part darkness, it is all about the monstrous challenge of leaping into the void, nothingness, and oblivion, while giving it coherence and complexity.

Verticality and falling characterise shows such as that by la Guarda, who stunned audiences at the Roundhouse in London in 1999, before going on to perform on Broadway for several years. In Bianco, directed by Firenza Guidi for NoFit State, the bodies that perforate a ceiling stretched above the spectators, and the dizzying vertical dance, add a joyful and transgressive dimension to a show that blends the aerial with the interactive, the audience's immersion with the rough skill of the acrobats, the pendular with the swinging, and links the sky to the earth in a paradoxical yet very efficient synthesis.

These creations take on a blend of pride, and pain, as well as nostalgia, because the matrix is never far and the framework of an aerial creation questions Icarus as much as it does Les Cigognes, as well as the adventurous spirit of Léotard, and the technical skill of many others, from the Codonas to the Vasquez.