The entry into circus ring of flying men

by Magali Sizorn

Aerial acrobatics is no exception to the rule, and was not invented in the circus ring. It stems from techniques that have been borrowed, adapted and transmuted. Taking an interest in the origins of "circus acrobatic flight" thereby means going beyond the history of the modern circus, which was born with Astley in the 18th century. It does not however, imply a vertical history of techniques and usages, nor invent a tradition (Hobsbawm & Ranger, 1983), or confirm a universal law, often invoked to describe a flight combined with the possibility of a fall. The circus is firstly a show, inspired by and drawing on multiple physical cultures and techniques (Mauss, 1950), coupled with acts, or even particularly fertile hybrid forms seen in the aerial acrobats' propositions.

Traversing the "infinite substance"

The sensation of freedom felt during a suspension, like a possible flight time, characterises the aerial practices and the imaginary worlds they result in. Ancient forms of exploration of what Gaston Bachelard calls the "infinite substance" are recognisable: swings in ancient Greece, and rope dancing in China during the Han dynasty, provided a glimpse of escaping from earthly constraints. The finalities of these practices are nevertheless extremely varied: expiation or fertility rituals, forms of propulsion toward the divine, shows, or more simply, banal entertainment and fun pleasure. In Europe, acrobatics above the floor developed mainly during medieval fairs and festivals, until the 18th century. In Paris, seventy acrobatic and rope dance companies were counted between 1678 and 1787 (Jacob 2001- 22), showing the elation of this game with gravity, and the exploit of conquering fragile equilibriums and the extraordinary nature of lightness.

« In the reign of the imagination, the air frees us from substantial, private, digestive reveries. It frees us from our attachment to matter: it is therefore matter for our freedom »

Gaston Bachelard, L'Air et les Songes, 1992 [1943], p. 175

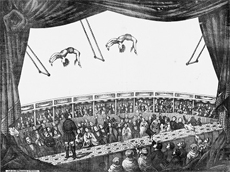

From the early days of Astley’s Amphitheatre in London, at the end of the 1770s, Philip Astley, occasionally associated with Antonio Franconi from 1788, incorporated rope dance exercises into his show programmes: the "aerial" forms thereby developed at the circus, adding acrobatic feats to the equestrian theatre, whereas fairs became spaces dedicated to entertainment, exhibitions and commercial expositions.

Exhibiting finely honed bodies: the influence of gymnastics

From 1850 onward, the first fixed trapeze and rings exercises appeared in the ring and the Italian Francisco brothers were applauded in London in 1852. Having given pride of place to equestrian work and pantomimes until the first half of the 19th century, circus programmes were now based on other exercises, stemming this time from gymnastics.

The origins of the trapeze are of course not only gymnastic, and once again, a complex web of invention, borrowing, and filiation exists. The invention of the trapeze, from the Greek trapezion, or small table, which was a popular piece of apparatus in ancient gymnastics, was therefore frequently attributed to the world of acrobats. The latter performed rope exercises, which then became flying exercises, on an apparatus composed of a horizontal bar suspended by two ropes joined at the top, known as the moving triangle (Strehly 1903; Thétard, 1947). This triangle was then used by Phokion Clias in his "callisthenics" gymnastic method composed of simple, moderate exercises aimed at young girls. But it was Colonel Francisco Amoros who finally claimed the invention of the trapeze in its current form (a horizontal bar suspended from two vertical ropes): his method was based on utilitarian gymnastics using apparatus that aimed to strengthen both body and mind.

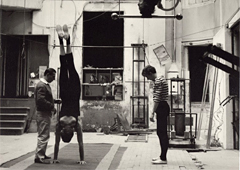

In 19th century France, gymnastics was becoming institutionalised, both at school and in the army, two areas particularly coveted in the competitive arena of physical exercises (Defrance, 1987). Private exercise rooms began to open in Paris and in the other major French cities. In the context of post-1870 France, numerous shooting and gymnastics companies were created that continued to develop these gymnastics methods.

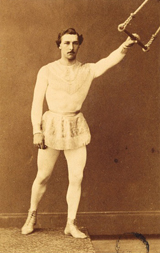

The circus then went on to create shows from this new genre of exercise (rings, fixed bars and trapeze), which had dramatic potential. At the fairground alongside Hercules, the gymnasts helped transform the circus into a space that valued beauty (Andrieu, 1993), mainly a virile beauty, as seen in the photographs and postcards of acrobats dressed in white, displaying skilful, honed physiques, all carefully trimmed moustaches and chests thrown out. Their poses recall both antique statuary and the entrance of circus practices in the history of educational gymnastics. The utilitarian exercises of these gymnastic methods, like the burgeoning practice of body-building, were thus subverted in favour of an opposing logic of the futile, the useless and the show form.

Dramatizing exploits: flying thrills

Show entrepreneurs contributed to the success of the circus and helped legitimise it at the end of the 18th century through the principle of a flexible programme and innovative staging procedures (Hodak, 2006).

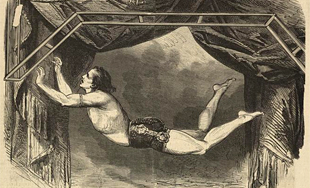

One of the innovations, a major one in the history of the circus, was the flying trapeze. The first act on this apparatus, Les Merveilles gymnastiques, La Course aux trapezes (Gymnastic Marvels, The Trapeze Race) was presented in Paris, in 1859 by Jules Léotard (1838-1870). The set-up, created in Toulouse in the Amorosienne gymnastic hall, was directed by Jean Léotard, his father, and enabled the acrobat to fly from " bar-to-bar". The trapeze artists thereby "gave the circus wings" and began a race of exploits, valuing excesses that recalled the values of Pierre de Coubertin (Andrieu, 1990). The circus use of the trapeze developed in the second half of the 19th century, when physical exercises became sportier (Vigarello, 2002), and the show trapeze moved away from all military purposes.

With the development of aerial acrobatics and the invention of the flying trapeze, several innovations helped strengthen the emotional response in a programme based mainly on ritual risk-taking being presented as a show. The main aerial apparatus were created at the end of the 19th century, including the fixed bar and trapeze, the rope and the flying trapeze (moving towards flying from a pusher instead of from bar-to-bar), and the Washington trapeze. Additional combinations between gymnastic apparatus and, mainly, technological innovations (such as trapezes suspended from hot air balloons) also appeared. This era also saw the appearance of sensational attractions such as human arrows and female canons.

Dramatic impact was based on ever more complex physical techniques and moreover, on an underlined visibility of the difficulty and the danger involved. This was part of the "tacit agreement" that unites actors and audience, and death was now a part of the game (Caillois, 1958).

Landmarks and references

by Christian Hamel

The rope. In 18th century prints, you can see funambulists varying their exercises by hanging from their ropes to execute figures while swinging. This was the first form of aerial work in the circus. It gave rise to the cloud swing, a rare speciality today, illustrated by the Czech Dewert, who would swing into the void with his his ankles held by the rope, and perform flexible contortionism while swinging.

For a long time the vertical rope or aerial rope was above all, a climbing method. At the 1896 Athens Olympic Games, a test of speed and height had been organised, but in the circus, the vertical rope was valued from 1860 onward by the sisters Nathalie, Léontine and Blanche Foucard, whose father, the Imperial Prince's instructor, ran a gymnasium on the rue du Bac. They also won renown on the trapeze, like Leona Dare (Adele Stuart), nicknamed the princess of the Antilles, who attached her trapeze to Eduard Spelterini's ball, and hung there from her jaw. She also hung by her jaw from a hook to descend a cable on a 45° incline. By attaching a leather ring to the rope, several artists suffered multiple arm dislocations, like the tragically famous Lilian Leitzel, who died on February 15th 1931, following a fall two days earlier in Copenhagen during this exercise. Others such as Tosca de Lac and Chrysis Delagrange preferred the grace of aerial postures inspired by dance. The Russians came up with the name "rope of peril" to describe this apparatus for which, in 1987, Nikolaï Chelnokov presented new suggestions with several levels of winding, planks and falls. Later, this artist created the aerial net for his son Anton. Duo work on the rope began with Elena and Zaida Chevtchenko in the 1970s. Since then, couples such as the Vitaly duo and Oxana Bobrov, Maxim Kozlov and Inna Mayorova, have perfected the acrobatic level while respecting the harmonious compositions.

The trapeze. The invention of the trapeze was the true starting point for aerial acrobatics. Colonel Amoros claimed to be its creator in his Manual of physical, gymnastic and moral education (1834), noting however that the discovery of the art belonged to the Italian funambulists. Before him, the Swiss Phokion-Heinrich Clias had created the "moving triangle" or a baton suspended by two ropes tied at the top to form a triangle. Those of the colonel were moved away from the point of attachment to form a trapeze. Later, in the definitive form, the ropes were made parallel.

The trapeze was used either fixed or swinging. It enabled imbalances, falling from the toes or heels, nape or lower back, falls that were recovered sometimes with twirling legs, ankles or heels. He discovered characters such as Winnie Colleano and Fritzi Bartoni, who succeeded in carrying out an extraordinary forward dive before recovering, at the last moment, by using the heels (without a safety line of course).

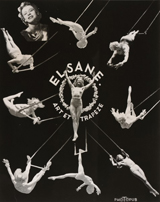

A French school reigned in the rings worldwide in the 1950s, with, among others, Miss Elsane, Betty Stom, Maryse Bégary and Andrée Jan.

In the 1980s, a generation of prima donnas including Elena Panova, Marina Golovinskaya and Natalia Jigalova, arrived from Russia, combining the grace of the Bolshoi with the rigour of aerial acrobatics. Tamara Khurshudova performed a daredevil act recovered on the trapeze bar, a performance currently successfully performed by Nikolay Kunz. Others such as Uuve Jansson and Lisa Rinne have pushed the limits of the discipline even further, using a safety line and protecting their thighs, ankles and calves.

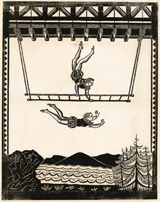

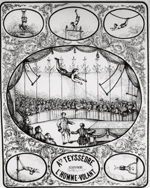

Aerial acrobatics. The first images of an acrobat flying into the air between two pieces of apparatus dates back to the mid-19th century. Jules Léotard, from Toulouse, was the first to execute passages from one trapeze to another. He developed the technique in his father's gymnasium, and performed it for the first time in public in Toulouse, in the Montesquieu hall on February 5th 1859, before performing at the Cirque Napoléon in Paris on November 12th of the same year. The mattress aimed at catching falls was quickly replaced by a protection net that was easier to install. From 1834 onward, Colonel Amoros sued this type of protection for his aerial apparatus. Around 1855, Thomas Hanlon presented a form of acrobatics, l’Echelle Périlleuse (the perilous ladder), where he swung from a bar and caught hold of a vertical rope. We can also mention the Hiram Day and Davis duo who swung between two cloud swings at the Nathan Sands and Co circus in 1856.

Léotard gave the flying trapeze its universal form, and from the creation of his number onward it was frequently copied. Its originality lay in providing a continuity of exercises, whose back and forth movements were facilitated by a person who would push the acrobat back. Shortly afterwards, the Hanlon brothers took up Leotard's idea, naming it Zampillaerostation for the occasion.

The Rizzarellis perfected the number by springing up from a trampoline to catch hold of the trapeze. By extension, acrobats such as Onra (Emilio Maitrejean) and Lulu, shot out from a canon and were caught by a catcher.

The aerial cradle. Some acrobats placed two trapezes one on the other to enable a catcher placed below to catch the acrobatic falls of the above partner. From 1906 to 1912, Jean and Eddie Ward worked on this double trapeze with recovered falls in which feet were caught under armpits and, even more difficult, feet were caught by feet. It was not until 1944 that these exercises would evolve, with the Géraldos (Madeleine and René Rousseau), and then again in the 1990s with the South African Ayak Brothers who, with wide swinging movements, risked falls and jumps hitherto reserved for the aerial cradle, but without a safety line.

The cradle was inspired by a version of the Hanlon's catcher-to-catcher acrobatics. It was a sort of fixed rectangle where the catcher hung from his calves and blocked himself with his feet. This speciality sometimes benefitted from morbid publicity (the leap of death!) with the Clérans and some others, but Joël Suty and Isona Dodero, trained at the Cnac, opened the way for new propositions in which choreography and performance found a thrilling balance. The French duo Aragorn also performed one of the most accomplished forms of this discipline.

The fixed aerial bars were introduced by Avolo in 1878 with three bars, and the Romanian Trojan Luppu added two additional bars above this, and his version was extremely successful with Mexican Rodriguez in the 1960s and 1970s. Valentin Gneushev enhanced aerial bar work by creating Perezvonyi (Chimes) set to a symphonic piece by Valery Gavrilin, an act inspired by Dostoievski's tortured world, which was taken up again in two Cirque du Soleil shows, Mystère (1993) and Alegria (1994), with the aid of Gneushev's former associate, choreographer Pavel Brun.

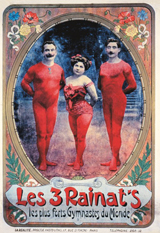

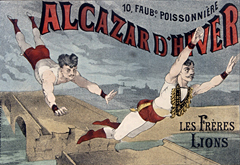

Trapeze races, a race for exploits

The first somersaults from one trapeze to another were successfully performed by Léotard, then copied by Victor Julien and a woman named Azella. From then on, the trapeze art would evolve in two directions: one saw jumps from one trapeze to another (baton to baton), and the other saw a catcher enter the game. The double from baton to baton was the object of stiff competition between Niblo (Thomas Clarke), Bonnaire, Victor Julien and Edmond Rainat, who all claimed it, but the Rainat was the only one to perform it successfully in front of people. He also successfully carried out a triple in rehearsals. Rainat and his companies were on the programmes of the most important European circuses, introducing new formulas to the apparatus, whereby acrobats flew past each other in the air.

A reduced form of the work covering smaller distances with a catcher in the cradle and often comic flyers such as Charlie Rivel, appeared in the 1920s. Mauricius (Maurice Neuville) remains one of the few to have successfully performed the double in this configuration, along with Stéphane Drouard, a contemporary acrobat who also turned a triple from baton to catcher.

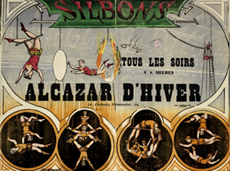

The latter formula, baton to catcher, really originated in 1877 with a company led by the Marquis de Gonza, who was attached to the bar by his boot hooks and caught Azella, mentioned above, and an acrobat named Lunardi. Using the same arrangement, in 1882, Walter Silbon performed a double daredevil (forward jump) and was caught by his father Cornelius. In 1892, his brother Eddie performed a double somersault (backwards) caught by Toto Sigrist. The conquest of the triple somersault gave rise to an extraordinary saga strewn with accidents, dramas and astonishing successes.

In 1890, Mamie Jordan was the first woman to turn a double somersault caught by her husband Lewis. In this family, the Flying Jordans, a pupil named Lena would perform the first triple in history, first from catcher to catcher (swung by a catcher installed on one trapeze and caught by another swinging catcher). Om May 18th 1897, she performed the triple from baton to catcher at the Sydney Royal Theatre. These exploits were verified in the 1897-1989 seasons.

The first male-performed triple is attributed in 1910, to Ernie Clarke, who worked as a duo with his brother Charles. One can imagine how difficult it is to catch the trapeze at the right moment as it comes back. Beyond the triple, Ernie Clarke performed the first double with a pirouette, and the first fliffus (double somersault with a half pirouette caught at the trapeze bar held by the catcher).

In early 1937, Antoinette Concello was the first woman to repeat the exploit of Lena Jordan at the Detroit Shrine Circus with Edward Ward junior as a catcher! The Mexican, Alfredo Codona wrote the legend of the triple by performing it regularly from 1919 onward, with his brother Lalo as catcher. Films from the era show the image and attitudes of a classical dancer with pointed toes, an arched back, and impressive control of his movements. His double and a half begun suspended from the bar has never been equalled.

Another exploit from the era that has never been equalled is the Melzora's "majestic leap," in which a flyer turns a backwards somersault passing by his partner. The exercise is extremely dangerous as you have to be very high up in order not to bump into your partner. The first triple and a half was successfully performed by Tony Steele, caught by Lee Stath, on December 29th 1962 in Durango (Mexico). The American Don Martinez remains the only person to have succeeded this trick for more than twenty years. It was a dangerous trick, for if caught badly, by the feet, the acrobat's head is very close to the net and there is not much time to recuperate. Don Martinez also succeeded in performing another feat: the double and a half with pirouette, also difficult to catch, as the catcher must compensate for his partner's rotation, and also catch him by the feet.

Quadruple and more

On July 10th 1982 in Tucson (Arizona) the Mexican Miguel Vasquez performed, in public, the first quadruple in history, with his brother Juan as catcher. He also succeeded in the triple with pirouette.

Reducing the history of the flying trapeze to the search for a number of turns and the complexity of somersaults would be unjust for those who have enriched the discipline, such as the Russian Evgueny Morus, who set a swing below a footbridge to allow flyers in the Galaktika act to head off on a quest for the stars, the theme of the act. Another Russian, Piotr Maistrenko, staged a veritable aerial ballet, the Flying Cranes act, inspired by a famous Russian song by Rasul Gamzatov, in which dead soldiers are transformed into cranes. Several trapezes and a net, used as a stage, enabled the combination of dramatization and aerial acrobatics in three dimensions. His other creation, the Borzovi, offered new forms of aerial acrobatics in the same vein.

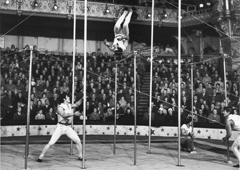

In Pyong-Yang (North Korea) in 1952, a flying trapeze school was created which developed aerial acrobatics by multiplying the arrangement of apparatus with fixed bars, swings, cradles for standing catchers, attached to the frame by a leather belt, and teeterboards. Kim Song Hui was the first woman capable of regularly performing the triple from baton to catcher, caught by Kim Yong Nam. Around 1992, Hong Gum Song successfully performed the quadruple, also caught by Kim Yong Nam. In 2011, for the first time, at Weltweihnachts Circus in Stuttgart, a man and a woman successfully performed the quadruple in the same act, in the classic baton to catcher formula. It was also in Stuttgart in December 2013, that Han Ho Sung performed the first quintuple in history, from a trapeze that started off at a very great height, towards a hanging catcher. At the same time, in Amsterdam, Pak Mi Gyong turned four somersaults during his flight from swing to catcher, and the flyer Kim Huang Mi flew fourteen metres from swing to catcher.