by Magali Sizorn

An apparatus stemming from gymnastics and physical culture, the rings were used like the trapeze and the fixed bar in circus acts from the mid-nineteenth century onwards.

Cross my heart…

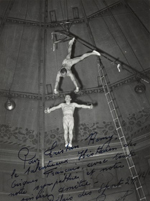

There can be no lying on the rings. Planks, suspensions, thrusts and twists tolerate no weakness. Balancing on your hands, fighting gravity to remain at right angles between the wooden or metal bars entails more than audacity (falls are rare), and it is the control of a honed, taut, muscular body that is appreciated. In the 19th century, when these figures, now classics, were already presented in rings, the audience came to admire the gymnasts, whose exercises, transformed into a show form in the ring, recalled that the era was one in which work on the body was developed in a reasoned way. Georges Strehly, a major promoter of gymnastics, mentions, in his work on acrobatics, several remarkable acts dating from the end of the 19th century, mainly those of the Nighton trio, or the Donnal's "triple plank." Increasing the number of acrobats on a single apparatus helped make the ring work more spectacular, as this work was often austere in its demonstration of technical skill and physical power, by gymnasts with well-trimmed moustaches and tight-fitting gymnastic outfits.

Strong women, too

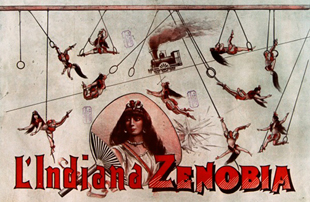

In the circus ring, and in contrast to current gymnastic rooms1, the rings are not an exclusively masculine domain. From the 19th century onward, female rings artists presented acts, damaging the traditional contrasts of strong-male and weak-female. However, the identity treatment was taken up again, and even today, in traditional circuses, aesthetic codes show the enormous gap between men and women: high heels, smiles and polished grace aim to erase the suspicion of insufficient femininity. Moreover, criticisms of virile women are frequent in the history of the circus, and often go hand-in-hand with too much proximity between circus acts, physical culture and gymnastics. In 1977, Francis Ramirez wrote, "the risk run (by women), especially on the perch and rings, is of developing excessive musculature […] That is where classical ballet can polish attitudes and make the harsh effort seem more supple, through grace." Lilian Leitzel (1892-1931) incontestably marked the history of the circus with the dramatic and biographic dimension of her work, as well as the quality of her act. "The American star" (she worked for Ringling Bros and Barnum & Bailey for a long time) was invited to appear in numerous European circuses, and she died in 1931, in the Valencia Music Hall in Copenhagen, following a fall during an act (the snap hook on one of her ropes accidentally opened). At the time, she was married to the famous flying trapeze artist, Alfredo Codona, who also came to a tragic end. In the ring, the woman whose physique had been described as "ungainly" by some (Thétard, 1947, 377)2, filled audiences with wonder, and "became beautiful in action owing to her ease and the perfection of her work." She first pulled herself up on the rope, then performed various suspensions, planks and turns on the rings.

Another female figure and "queen of the rings" was Dolly Jacobs (1903-1992), the daughter of an American clown Lou Jacobs, who won several prizes for her act on the swinging rings, notably in 1988 with a silver Clown award at the Montecarlo International circus festival. Also trained on the flying trapeze, she introduced an acrobatic dimension to the rings acts, and concluded with a somersault, landing on a vertical rope. Demonstrating strength and flexibility, and combining classical rings figures and techniques inspired by the flying trapeze, she swung high under the cupola when she swung on her rings.

Between heaven and earth

Practising or combining the rings with other apparatus (rope, trapeze, etc.) "spices up" the rings according to Adrian (1988, p. 19). It is true that there is not much flying involved on the rings. The possibility of fall itself is barely suggested, as the acrobat holds on tightly, suspended, pulls himself up and stays in place. Finally, this apparatus is an invitation to multiple performances: the exploit of vertigo, of simulation as well, and those permitted with oppositions of heavy and light, strong and weak, masculine and feminine. All the above were admirably performed by Barbette, (whose real name was Vander Clyde Broadway, 1899-1973), a transvestite trapeze artist in the 1920s and 1930s, who appeared on stage dressed in feathers, then soared on the rings in a light suit. He blended strength and grace and shook up conventional patterns of appreciating gendered acts, before removing the ambiguity. When he took off his wig at the end of the act, his simulation was revealed.

1. The "swinging" rings were nevertheless practiced at a competitive level by women between 1938 and 1950.

2. Editor's note: She was generally described as "dainty" by her peers.