by Marika Maymard

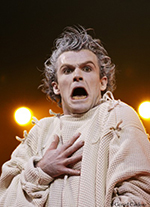

Multifaceted, the circus clown gradually builds on comic characters whose origins go back to the dawn of time. His main concern is the vital, liberating laughter, whose legitimate purpose requires all the tricks, all the vocabularies. Through satire, parody, the multiplication of crude, incongruous, senseless effects, he deflects logic, upsets the established order and leads men into a collective madness that is both harmless and serious. Indecent, jubilant, he causes their instant gratitude and some kind of rejection or disdain, often over time. Thus, marked by derision, the popular expression "to play the clown" reduces the comedian's work to a futile and annoying activity. A pejorative perception that affects more globally the saltimbanques heirs of joculatores, jugglers and other trick artists.

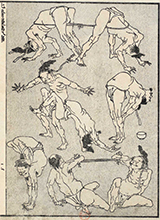

Born an acrobat

The comic actor who appeared in the circle of the nascent circus at the end of the 18th century did not yet bear the name of the clown from the English scene. According to its origins, it is referred to as a clown, a buffoon/jester or a paillasse. The clown who emerged in the middle of the next century was essentially an acrobat, according to Bouillet1: "The talent of clowns consisted mainly in performing balancing, flexibility and agility exercises, games in which many displayed truly remarkable skill and dexterity". A vision taken up by Alfred Delvau2, who presents Léotard, the precursor of the flying trapeze, as a clown, or by the writer and gymnast Pierre Loti, close to the Frediani family, who describes his participation as an acrobat at a gala evening at the Cirque Toscan: "I will appear tomorrow with the Cirque Étrusque in clown mask, clad with a yellow and green jersey3 ".

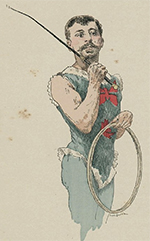

Rider... dismounted...

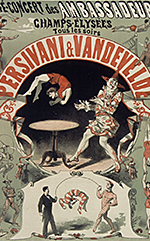

Before the end of the 19th century, it was not easy to practice your art in the world of entertainment, dominated by the privileges granted to official theatres, where, among other things, the banquistes were not allowed to express themselves. In this context, the first clowns on the ring are equestrian acrobats who ride a horse in an eccentric way. The first would be Billy Buttons who appeared at Astley's Amphitheatre in London in 1768 in La Course du Tailleur en route pour Brentford, which was repeatedly adapted by changing the names of the characters according to the different countries. Other merry-go-round scenes feature Antonio Quaglieni dressed as Madame Angot at Franconi's or Tom Belling's, this clumsy "Auguste" from the Renz Circus, with his vermilion nose of a drunkard who can hardly stand on his mount. Belling even created in February 18814 a character of an Auguste female in a parody of an equestrian pas-de-deux, of "Mr Auguste and Mrs Auguste" in duet with Mrs Gontard (Caroline Strassburger), a comic scene that prefigures the exploits of the Mullens, Dutch aerial acrobats or the Swedes Svenson.

Jumping clown

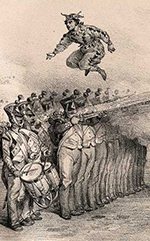

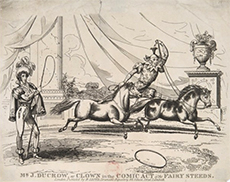

In 1819, Squire Ducrow brought the first walking clowns, Derwin, Garthwaeth and Blinchard, into the Franconi troop5. Actors in the English farce, they contribute with the grotesques from the Olympic Circus, including Gaertener (or Guerdener), praised as a real phenomenon6, to drawing the contours of the circus comedian on the ring. Incredible jumpers like Little Wheal, Chadwick, Griffith or William Kemp trigger laughter by performing serious exercises by definition such as the somersault. Théophile Gautier observes the lyricism of the silent comic actor, skilfully intervening in the plot of a circus pantomime. Already thrilled by Lawrence and Radisha's performance, flexible frogs in Les Pilules du Diable, on the Olympic Circus programme in 1837, he simply couldn't find any strong enough words to celebrate the clown Auriol. Even bolder than Gaertner, wearing a hat with small bells borrowed from Gontard, the mythical jumper, likened to a bird man or a flying squirrel, launched himself by pirouetting over a regiment of men, with fixed bayonets, or through a hoop covered with clay pipes without breaking them7, while shouting his famous "Là!" with a flute-sounding voice.

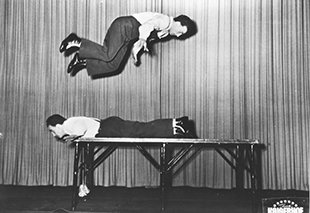

When the rhythm of the jumps accelerates to multiply the comic effects, the clown, who was a jumper, becomes a stuntman. Inspired by the Price brothers, the Hanlon-Lees, explosive English "Black Pierrots", pushed the limits of their prowess so far as to dare to take foolish risks. Through the clever chaos of the stunt groups' tumbles, the real clown can lose his identity in favour of a collective madness whose expert synchronisation aims to surprise the spectator. Adapted to the music hall scene as well as in the ring, the formula is constantly reinvented with the Crosby, Craddock, Bono, Charlivels, Pauwels, Manetti Twins, on the table, or Platas, all European, but also the Yankov, Russian or Halfwit's, American, on pommel horse like the Spider Austin.

Handing over

In the ring, jumping clowns, mime clowns and talking clowns gradually rub shoulders, heirs to the cynical verve of the jester, a concept claimed by W. F. Wallett8 and embraced by George Foottit at the end of the 19th century. The acrobatic heritage is reinvented to be transmitted. The upright bottles, laid down and then straightened under the footsteps of Jean-Baptiste Auriol, were found a century later under the clogs of Johann le Guillerm in Où çà? Jamie Adkins makes the ladders dance in Circus Incognitus, a little like James Boswell, "the gentleman paillasse"9, stripped his own steps as he climbed the ladder so he could have a toast, with a glass in hand, in a headstand at the very top of the remaining pole. In the tradition of a Candler on a pole or the Price Brothers, creators of the animated Ladders climbed while playing the flute and a violin, Moïse Bernier, a clown at the Galapiat Cirque, moves along a mast without stopping playing the violin in Risque Zéro. Under the impetus of Lucho Smit, all the company's creations weave with humour very physical relationships with the environment.

From one century to the next, practices have always been intertwined. Thus, the eccentricities of Bill Randall with his elastic board at the end of the 18th century are echoed in the trampoline antics of Super Sunday, by the contemporary company Race Horse. The contemporary circus tends to exploit all dimensions of the spectacular space by confronting acrobatic talents with a clownish approach that, depending on the artist's purpose and commitment, activates poetic, playful or even caustic touches. In Extrêmités, the artists of the Cirque Inextrémiste joyfully challenge fatality by confronting it head-on. In precarious equilibrium on long boards swaying on gas bottles, they taunt the danger until they engage Rémi, a paraplegic acrobat, in a performance whose audacity alternates between petrifying the audience and throwing them into fits of laughter.

1. M.-N. Bouillet, Dictionnaire universel des sciences, lettres et des arts, Paris, Hachette, 1854.

2. Alfred Delvau, Les Lions du jour : physionomies parisiennes, Paris, E. Dentu 1867, p.179.

3. Pierre Loti, from Un jeune officier pauvre, published by Samuel Viaud in 1923.

4. Alwill Raeder, Der Circus Renz in Berlin, season 1896-97.

5. Adapted from Tristan Rémy, Les Clowns, Paris, Grasset, 1945.

6. La Pandore, 5 october 1823, reproduced in Le Miroir des spectacles, des lettres, des mœurs et des arts, vol. 2, 1825.

7. Théophile Gautier, Histoire de l’art dramatique en France depuis vingt-cinq ans, vol. I, Bruxelles, Hetzel, 1858.

8. William Frederick (1813-18), The Public Life of W. F. Wallett : the Queen Jester London, J. Luntley, 1870. Quoted by John Stewart inThe Acrobat : Arthur Barnes, London, McFarland, 2012.

9. Ernest Blum, « Adieu à Boswel » (sic), in Le Voleur, 20 may 1859, published in Le Cirque dans l’Univers n°43, 1961.