by Pascal Jacob

The clown arts, a complex concept to define as it borrows from intricate and complex forms to become formal, is probably marked above all by its capacity for mutation. Today we no longer laugh at the same things as a century ago and the figure of the clown does not escape the changing intentions that are characteristic of a character born in the theatre and whose formulation, both in terms of repertoire and appearance, has never stopped moving. The contemporary circus does not compose with the clown as systematically as a more conventional circus and undoubtedly delves deeper into humour and comedy rather than relying on impulsive and easy laughter. In recent decades, the clown has also established himself in one-dimensional shows, such as acrobats or jugglers, and this dimension has a definite impact on performance and scenic writing.

Precursors

Whether it is conversational or simply mime, one of the founding axes of the clownish register is the repertoire. Forged in the 18th century on the playing field outlined by Philip Astley, it was embodied in 1768 in La Course du Tailleur à Brentford, a comedy sketch where a clumsy rider could not control his horse and was constantly biting the dust. Astley himself interprets this initial sequence, which synthesises all the ingredients of the modern circus: the circle, the horse, the acrobatics and the laughter. This first fusion of devices is symbolic. It anchors the circus in the cross-sectional nature of its practices and above all announces the importance of a singular register, humour, to counterbalance the strong emotions induced by vaulting and balancing.

This "adventure" of the unfortunate tailor, inspired by a news story at the time, has a strong political connotation, linked to the controversial election of politician John Wilkes. Philip Astley captured it and made a first successful appearance, but he could not imagine how much this creation would encourage revivals and adaptations from one side of the world to the other. Rognolet et Passe-Carreau, Billy Buttons, from Paris to New York, made this equestrian parody popular until the end of the 19th century. It was designed in a few days to reflect a very quickly forgotten news item. Nonetheless, in a few seasons, the Tailleur has become a leading figure in the repertoire.

Codifications

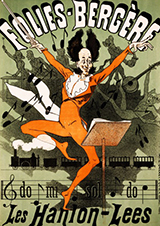

This mobility of forms is characteristic of the evolution of clowning. The first "walking clowns", inspired by the Shakespearean jester's silhouette and Joe Grimaldi's appearance codes, helped to define the main lines of a very physical vocabulary that would continue to grow over the seasons as new practitioners regularly appeared, like today's clown such as Ludor Citrik whose fierce energy and physical presence were part of that symbolic continuity embodied by the Hanlon Lees in the 19th century.

This tension between pace and interpretation, defined in particular by the prohibition to speak in words until the fall of the Second Empire in France, is nevertheless fertile. Above all, it highlights the body as an essential device and turns the first clowns into comic acrobats. It is a founding concept, even if as words gradually emerge, flexibility and physical strength become part of a preliminary base rather than a mandatory set of specifications. Gradually, the clown repertoire became more formal and codified, essentially to meet the needs of the first duets, founded at the end of the 19th century. As symbolic as it may be, the need for a written narrative leads to unusual formulations, similar to the rudimentary canvases of the commedia dell'arte, identified under the simplified term of comic entrées. The aim is to support the performers by offering them a framework that can be used as a starting point allowing them to work according to their individual personalities. This is a highly effective "way" of defining the role of the clown and the Auguste, and it will stand the test of time without really evolving until the second half of the twentieth century. Like the circus as a whole, the clown then begins a profound transformation, both in his ability and his appearance.

Elsewhere

At the end of the 1960s, between difference and reverence, clowning escaped from the circus to develop its styles and modes of creation. It now flourishes in the street or on the stage, which were its first territories a few centuries ago. Les Clowns from Ariane Mnouchkine and the Colombaïonis, a duo of acrobats from the traditional Italian circus, but entirely invested in reinventing clown mechanisms, particularly driven by the energy of the commedia dell'arte, represent essential milestones in this spectacular transition process. While Ariane Mnouchkine dramatises her relationship with the clown, the Colombaïonis fuse the organicity of Italian comedy and the original innocence of the Auguste to create singular characters capable of improvising as well as playing very well-written sequences. By appropriating classical clown entries, like Hamlet's and William Tell's parodies, they drastically shift the perception of a repertoire considered naive and outdated. There is of course always an apple, but the initial mechanics of the entrée has become above all a magnificent pretext for a dazzling demonstration of virtuosity, without the slightest artifice, based on verbal spontaneity and an ability to constantly react quickly according to the audience's reactions. This extreme availability at all times, this way of breathing with the audience and modulating each intention according to the vibrations generated by the spectators, a bit like a surge of shared creative energy, the group unknowingly inspiring the attentive duo that is open to the slightest hint, with their intentions for the performance, is a remarkable stylistic exercise that significantly disrupts the accepted feeling. To some extent, Ariane Mnouchkine is paving the way for several generations of female clowns. Three years after Les Clowns, Annie Fratellini creates her duo with a clown, but many women will also choose to perform as a solo artist. Léonie, Madame Françoise, Emma la clown, Hélène Ventura, Jackie Star or Arletti impose their characters over the seasons, often on stage, but sometimes also in the ring.

Appearences

The Colombaïonis also shift the clown's visual perception: where Ariane Mnouchkine absorbs the codes of representation and appearance while keeping rags and red nose, they leave aside the expected elements of the clown's wardrobe to enter the stage, or to go in the ring, dressed like spectators. A few accessories complete the shirts and trousers according to the scenes, but nothing distinguishes them except their physical density, which is apparent as soon as they appear. This simplification is also decisive for the approach to the characters and it is not insignificant to have in front of you two characters capable of being in turn the clown or the Auguste, both swapping registers to turn into targets or despots. This "minimisation in appearance" is also common to a duo formed in the early 1990s by Aleeksenko and Jigalov, partners defined according to their respective physical singularities. The first is tall and elegant, the second is small and clumsy. Their comedy is born both from this strong contrast, but also from their ability to put into perspective the boundary between authority and disarray, accuracy and imprecision. Both are simply dressed, changing their outfits according to the entrées, but they are very far stylistically from the classic wardrobe. Timour and Konstantin, also trained in Moscow, are in the same vein, developing a slightly offbeat clown style while creating their own versions. Initially, Carlo and Alberto Colombaïoni also performed some entrées, notably for Dario Fo, but they quickly developed their own shows, thus introducing another dimension to the clown register. This new relationship to the stage and the audience is decisive for the evolution of clowning. Since the 1980s, it has been an attractive mode of creation for artists, but it inevitably leads to an abandonment of the entrée, a format adapted to a multi-faceted show.

The silence of words

In founding the Licedei collective, Slava Polunin relies on a very traditional and very coded clown register, but one that is already symbolically offbeat. His fascination for Leonid Enguibarov's work nourishes his practice and he adopts stylistic choices that will contribute to the evolution of the clown arts in the Soviet Union. The definition of the silhouettes of the group's various characters, between the purity of a traditional form and the translation of an immemorial image, is stimulating. There is here a reverence to the flexibility of the frock of the paillasse as flexible references to childhood and innocence. The creation of La Route de Sienne, a show directed by Madona Bouglione, is a perfect symbol of this stylistic and technical evolution. The play, a previously unseen version of Roméo et Juliette, is performed by several members of the Licedeï collective, actors and dancers. Anchored both in the Shakespearean tradition of a performance entirely played by men and in the clown's tradition, the performance is a dazzling display of virtuosity. The Licedeï bring this mixture of anxiety and joy, which can nourish Shakespeare's poetry even if there is not a single word spoken on stage. Clowns bring to life an energy that is unique to them, enriched by an extraordinary appearance. Without a word, but with a confounding expressiveness, they transfuse a new freshness to a theatrical adaptation of an unprecedented power.

Others, such as Les Nouveaux Nez, Bert and Fred or James Thiérrée, challenge the repertoire and strive to revisit its codes to better transcend them. In La Symphonie du Hanneton, James Thiérrée inserts an "old" entrée, the Miroir brisé (‘Broken mirror’), but gives an adaptation of a dazzling intelligence. Facing his double, dressed like him in basic white pyjamas, he performed an early morning shaving session punctuated by the music played on a transistor radio. Each of the "reflections" engages or interrupts him and if the structure of the entrée is carefully preserved, it is nevertheless subtly shifted to become a very contemporary comic sequence, inspired by an old script. The conventions of the "mirror" are respected, but the finesse of the interpretation perhaps makes them even more accurate than when the entrée is played with a heavy gilt frame. This inspired offbeat shift also suggests that some traditional elements finally have a bright future ahead of them.

The Monti trio, composed of a white man and two augustes, anxious to perpetuate a model and to shape its effects themselves, managed for a few seasons to interpret several traditional entrées, notably in the Roncalli circus venue. By styling their silhouettes while relying on their extreme complicity, the three members of this trio succeeded in accurately restoring the spirit that would have inspired the Fratellini while transcending their performance. This interpretation, however partial it may be, revives the memory, but it is also marked by a certain modernity. The Monti trio has been able to highlight the strength of tried and tested features without disrupting their structures, but others, like the Trottola company, were able to reinvent magnificent mechanisms. The whole Matamore show is imbued with the profound meaning of what has constituted the vis comica for several centuries and its way of creating its own dramaturgy with emblematic elements from history is remarkable. Powerfully embodied, the characters created by the company's artists leave their mark on the evolution of a clowning experience with inexhaustible resources.

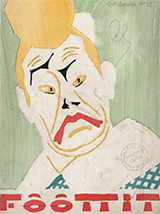

This evolution of characters, repertoire and appearance reveals an attachment to what intuitively underlies the principles of an atypical narrative, long linked to a particular context. The most notable evolution is undoubtedly the development of an increasingly abstract narrative process, supported by creative impulses and literary or pictorial intentions. What inspires clown forms such as Le Syndrome de Cassandre or Par le Boudu is both lively and indescribable, yet another way of thrilling the audience and leading them to places they do not always wish to explore. It is a fundamental break with what clown art has long generated during its integration on the circus circuit, even if some artists have sometimes held out to the public a distorted mirror of its own condition. Foottit did not hide this, asserting a part of his violence in the ring, even justifying it by the sharp observation of the behaviour displayed by his contemporaries. An uproar that finds a strange echo in the few lines intended to describe the moving and overwhelming Par le Boudu, created and interpreted by Bonaventure Gacon: "He's a little sick, too drunk... No doubt the liver, the small beers or maybe the heart itself, his poor ogre heart, or that damn rust that inexorably interferes with everything, stoves, hearts and everything else... Well, you have to get back to work, go see the good little guys and little girls, have a few drinks, watch the sunset, enjoy a few big meals and then be as mean and nasty as possible.

Well, you have to live!..."