by Philippe Goudard

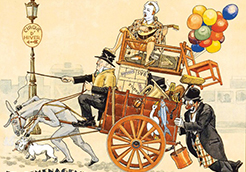

The great Richard Tarlton, one of the leading Elizabethan clowns, was famous for his improvisations based on the words thrown at him by the spectators and David Shiner invites his fellow performers to play roles in the numbers he offers them. Clown art finds its roots in the fun and pleasure shared by artists and their audiences, rooted in play and laughter.

Playing

Playing is a human constant characterised by the ability to abstract oneself for a moment from reality, to engage in a space of freedom. There is no such thing as a culture where it is absent. Several of its dimensions are of interest to clowns.

Essential to childhood, the play activity evokes naivety and innocence that are often highlighted in clown compositions. Sometimes kindly intended for the child viewers themselves, these actions seem spontaneous and gratuitous. But because they are the work of adults acting like children, they are tinged with strangeness. The costumes of some artists underline this. Charlie Rivel, dressed in a long red shirt where only his arms and shoes protrude, pronouncing barely a few words and moving with a slow and feigned clumsiness, is an eighty-year-old baby and Slava Polunine in large yellow pyjamas and slippers, a metaphysical infant.

The fact that playing is a pedagogical or therapeutic aid explains the effectiveness of clown art in healing, teaching or even business games. Their ability to invite a random dimension for pleasure allows them to arouse curiosity, stimulate creativity and defuse anxiety.

Playing rules

But playing is also an art. As the Elizabethan origin of clowns reminds us, they are first and foremost actors whose way is specific to each artist and participates in drawing his or her figure, pace and appearance, character and ultimately style. This art presents the particular characteristics of the play activity: free, cut off from reality, random, unproductive and organised. Because the power of distraction and relaxation found when playing, which the clown uses most often, must not hide the fact that the play activity generally has its own rules. The clown is a player and as such, follows a strategy. It allows him to structure and test his discoveries, to access his memory, his intelligence and his imagination. It transforms any information that reaches him into a new playing suggestion whose rules he will follow or break, for the joy or surprise – but sometimes stupor – of the audience he is playing with. One of the particularities of clowns, who weave their privileged link with the circus, is that the public likes to share with them the uncertainty and risk, to perceive in the qualities of the artist's performance his ability acquired through work, to play and bend the rules of the game.

Like other comic actors or actresses, clowns trigger chaos in and around them for our own pleasure, dissolving our anguish about disorder, failure and death into laughter.

Laughter

Laughter, among human emotions, is like play, a universal phenomenon. Physiologically, it is the occasion for facial expressions, it causes us to emit rhythmic vocal sounds of variable intensity and adopt postures and gestures that sometimes affect the whole body. It is a reflex, the excitement of which is sometimes physical (tickling) but above all psychological and intellectual. Laughter is born in a part of our primitive brain that has not evolved since prehistoric times, in cerebral areas involved in learning, memory, emotions, behaviour and personality. While it is genetically programmed, it is controlled and determined by cultural and social learning. Today, it is associated with pleasure, another physical and psychological phenomenon. We even laugh in unpleasant situations to compensate them with pleasure. This relief is produced by brain chemicals that bring us calm and euphoria. This is why laughter has a beneficial effect on memory, pain, learning, and reduces anxiety. As a result, clown art educates and heals through laughter as it does through play.

Theories of laughter

For Charles Darwin, laughter seems to be the primitive expression of joy itself or happiness. If laughter is caused by joy, it is also caused by what seems comical, ridiculous, laughable and humorous. From Plato and Aristotle to Descartes, Kant, Spencer, Bergson and Freud and up to the neurophysiologists of the 21st century, many thinkers and scientists have tried to answer the question "why do we laugh?". From their answers to this question, French doctors and psychoanalysts Henri Rubinstein in 1983 and Eric Samdja in 1993 proposed an effective summary in four different theories of laughter, where we find many mechanisms and components of clown art.

One of them connects laughter with a feeling of superiority over what causes it: physical, intellectual, moral and social inadequacies. The other is based on contrast and incongruity: laughter comes from the unexpected perception of a sudden change between what is expected and what is coming. Still another associates laughter with an emotional outburst occurring to release excess psychological tension created by a situation generating a great deal of effort or some anxiety, for example. The accumulated energy flows in this way to maintain the mental balance of the person laughing. Finally, one of the theories considers laughter as a means of regulating social and cultural life, by transforming the automatisms and inadequacies, in other words “some mechanism stuck onto the living” as described by Henri Bergson in his essay, into laughable objects. Each of these theories is complementary, which is perfectly illustrated by most of the comic effects used by comic actors who combine the different elements: we laugh at the clown who surprises us with his absurd decision (theory of contrast and incongruity), at the same time as his poor appearance (feeling of superiority), his almost frightening mask (relief theory) and to reassure us not to be like him (social and cultural regulation).

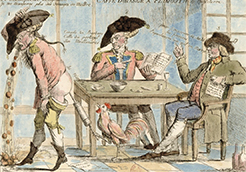

Moral or not?

The authors of the various theories of laughter are morally divided between those who consider it a benefit and those who disapprove of it. Depending on the time, social rule, ideology or religion, laughing is a virtue or a sin. Especially since for Sigmund Freud, humour and laughter help to free repressed emotions such as aggressiveness and sexuality. Indeed, laughter is linked to the notion of transgression and crossing the boundaries of decency established by a social group is often a source of comedy and laughter, whether they are authorised by the rules in force (show, carnival, collective meeting) or self-regulated by the person laughing on their own (silent laugh, chuckling). Many artists use them, especially women, if only because they assert themselves as comedians and clownesses, after centuries of devolved social roles, male rule, prohibitions and taboos.

Solitary or collective

Laughter manifests itself through several modalities, intra-psychic or noisy and collective. While humour is generally considered to be a phenomenon that occurs within the mind and intimacy of the individual, laughter is considered by many researchers to be a modality of non-verbal communication. Anthropologists observe organised sessions of collective laughter among Earth's first inhabitants for religious, therapeutic or social cohesion purposes. It is contagious. Sharing laughter allows it to be valued, to establish with other people laughing a guilt-free complicity, and to detach yourself from the comic situation. Sociologists observe that laughter needs an echo: "Laughter is contagious. It puts an end to man's loneliness." (Rubinstein, 1983).

A variety of experiences

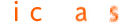

The emergence of laughter is an opportunity for various experiences. We can laugh at a funny form, the exaggerated make-up of an Auguste for example, but also at an absurd situation like Grock moving his piano to bring it closer to his stool that is too far away. Here we immediately perceive a strange shape. There our mind analyses a situation and anticipates the logical solution. There are nuances in the characteristics of the origin of laughter.

The laughable defines an element that is likely to make people laugh, of which the comical or the burlesque are sources of amusement. It is also pejoratively tinged with ridicule.

Humour is a form of spirit that underlines with detachment the unusual aspects of reality. It is black humour if it manifests itself about a serious or macabre situation. What makes people laugh through the bizarre, the original or the strange, is funny. The absurd is clearly contrary to reason, to the common sense, almost impossible.

Comedy originated in the ancient theatre where citizens wore masks. It is therefore linked to a notion of blurring the social class distinction, of staging characters of average or low condition in a daily context, unlike tragedy. The comedian makes people laugh through the detail of a situation, or even of an object, of a person, of their physical or moral behaviour. At the origin of clown art, we can see that play and laughter are intimately linked to the artists' performances and the pleasure we take in applauding them.