by Marika Maymard

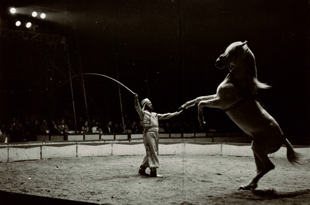

Embellish, transcend the ordinary, enchant the spectator in the time of great heroes with the help of an ever-changing performance by men and animals, offered to the occasional inhabitants of a universe built on a new planet, the circus theatre. From riding arena pieces to large equestrian dramas called hippodramas, dramaturgy has stepped into the ring since the creation of the equestrian circus 250 years ago. From the Scenic Riding Acts of Philip Astley or Charles Hughes to the contemporary equestrian theatre of Le Centaure, Zingaro or Baro d'Evel, the form and intention have never ceased to evolve. The training of the horse, considered as an artist and performer in its own right, is the result of a long evolution since the historical cavalcades that emerged from sand dust clouds and the smoke of the Bengal fires in the early days of the circus.

Tours and detours

When he opened his riding school in 1768, Philip Astley, former Sergeant Major of the Elliott Dragons, performed a series of quintes and quartes with his sword, standing perilously with one foot on his horse's rump and the other on his horse's head. For a century, from one side of the Channel to the other, posters advertise La danse comique du fermier français suivi d’une « hornpipe » et de la danse du drapeau intitulé The Graces (Londres, 1782) – (“The French farmer's comic dance followed by a "hornpipe" and the flag dance entitled The Graces (London, 1782)”) – or an Entrée de paysan grossier métamorphosé en paysan coquet dansant l’Anglaise (Paris, 1794) – (“Entrance of coarse peasant transformed into a coquettish peasant dancing the English dance (Paris, 1794)”). With the discoveries of "antiquities", references to Greek and Roman mythology and statuary flourished. Athletes on horseback evoke Le Vol de Mercure or La Renommée or take studied academic poses, standing or kneeling on the animal's back at a gallop. The riders restore the carousels and tournaments, variations of the Pumps and Triumphs of the Roman Empire.

Riding arena pieces

In a highly regulated context where the circus is likened to a "curiosity show", its pioneers are constantly seeking to have their establishments recognised as "theatres". Deprived of speech, their "actors" are dedicated to telling stories through mime, enriched with performances and special effects. Heirs of the drolls, these small, short, extravagant and quickly shaped pieces, thrown into complete illegality during the four centuries of the Puritan regime in England, the riding arena pieces are created around simple arguments. La Vie du soldat ("A Soldier's Life"), La Noce du village ("The Village Wedding") or Le Carnaval de Venise ("The Carnival of Venice") are pieces with a clothing transformation where Paul and Bastien, standing on the bare horse, are excellent at Cirque Olympique. The world of entertainment is permeable, and the protagonists observe each other. Characters who appeared in the theatre were immediately the subject of small "series" in the circus, such as Fanchon la Vielleuse, a comedy by Bouilly et Pain (1803) followed by Frère de Fanchon ("Fanchon's Brother") or the adventures of La Marquise de Prétintaille (Dumanoir et Bayard, 1836). The narrative form is expanding and broadening. Various mimodramas in several acts are developed. Thus, in 1825, a version of Lord Byron, Mazeppa (1819) written by Léopold and Cuvelier for the Théâtre du Cirque Olympique was published : Mazeppa ou le cheval tartare. In 1830, La poursuite de Fra Diavolo, Auber's opera on a libretto by Scribe, revived the myth of the heroic robber in a major cavalry deployment.

The time of pantomimes

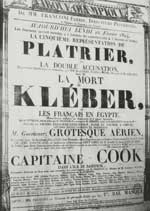

The nature of the theatres' agreement determines the type of performance allowed. The Hôtel de Bourgogne or the Opera can only ride a horse on the stage... led by a Franconi! Circus companies, classified as minor theatres, were banned from performing spoken word plays, which precipitated the production of high-profile equestrian pantomimes, in the same vein as La Mort de Marlborough, which Antonio Franconi performed alone at the Amphithéâtre des Brotteaux in Lyon in 1792. The squires surpass themselves in the pursuit of outlaws as in Le Renégat et la belle Géorgienne (1817) or La Famille d’Armincourt et les Voleurs (1812). From crusades to Napoleonic campaigns, these performances offer an audience exalted by the brilliance of brass and the smell of powder, hand-to-hand horsemen trained by real or legendary heroes, from Ulysses to Murat, Robert le Diable, Henry IV or Don Quixote. In the Astley Amphitheatre, the names of the great Shakespearean characters cross those of the heroes of the day, like Franconi's old enemy, Wellington, who defeated the French in Waterloo. The booklets of the Olympic Circus meticulously describe the details of the actions, down to the smallest mimed expression. They bear the signatures of authors, music composers, set and costume designers. But no dialogue.

Evolutions

For the purposes of the action, the structure and scenography of the circuses are being transformed. From the beginning of the 19th century, the ring was regularly connected by wide wooden ramps to a stage perfectly equipped with slides, undersides and arches. A juxtaposition of spaces that allows to widen the field of action, to integrate sets and for riders to simulate spectacular bouts. The success is such that Antonio Franconi succeeds in obtaining an exemption to introduce dialogues and even choirs into his lifelike productions, which awaken and maintain the patriotic feeling of the crowds. Hence Jules Claretie's reflection in 1910: "There would be a thesis to write (without any paradox): Franconi's influence on the return of the Empire".

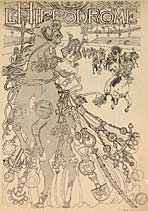

In addition, Antonio's sons continued the father's work: initially at the Jardin des Capucins in rue du Mont Thabor, then in Faubourg du Temple. Henri, known as Minette, stages the pantomimes and Laurent trains the animals and leads the rides. The creation of hippodromes offers a new space, ideal for the development of great epics. History unfolds its splendour and drama, in ever-increasing deployments of horses and extras, from Le Camp du Drap d'or, created in 1845 by Victor Franconi at the Hippodrome de l'Étoile, to Vercingetorix, which, on 13 May 1900, inaugurated the Hippodrome de la Place Clichy. Announced as fairy tales, parades and cavalcades are a little too strong for the performance and remain worthwhile thanks to the spectacular chariot races and the sensational 15 or 20 horse riding display.

From historical pantomimes to circus operettas

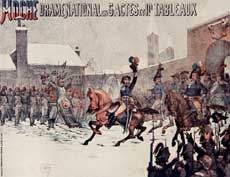

Throughout the 19th century, the horse, as a companion and partner of man in the city and on stage, was educated to practice academic equestrian exercises as well as to perform and execute the stunts associated with mime dramas. The various episodes and twists and turns of military campaigns provide themes and opportunities to restore the sense of belonging and national pride of French people traumatised by the 1870 defeat against the Prussians. At the Cirque National (National Circus), which became the Cirque d’Hiver (Winter Circus) in 1873, Adolphe Franconi went through times and regimes by changing the colour of the flags. For a century, theatres and circuses have been recreating invigorating Napoleonic victories. Besides recurring themes such as chariot races and hunts adapted from ancient games, the narrative vein of pantomime authors is also inspired by distant conflicts: the wars of the Caucasus or Crimea, the Sino-Japanese conflict, offer the opportunity to renew the public's curiosity and entertain visitors' desire for escapism. An artistic team assembled by the circus management is working on uniforms, sets, costumes and exotic or oriental musical compositions.

The 1889 and 1900 world exhibitions in Paris attracted crowds of provincials and foreigners who were fond of entertainment. Opened in February 1886 at the initiative of Joseph Oller, the Nouveau Cirque de la rue Saint-Honoré is designed as a sumptuous setting for the exercises presented, mainly equestrian, as well as for invited attractions and an audience in evening wear. Equipped with a ring that can be transformed into a swimming pool, it is designed for both summer and winter opening. During the theatre season, the wooden floor protected by a coconut mat is retracted after the second part of the programme to let the almost 14-metre diameter tank fill with water pumped from the Seine river. A pretext for large enchanting or comic scenes, its aquatic area is decorated with scenery and is enlivened by dozens of extras in addition to the elements of the troupe. Written by Donval, Agoust or Surtac and Allevy, all the scenarios feature a gigantic final dive by human and animal artists.

At the turn of the 20th century, the interaction between the circus world and the travelling fairground economy, dominated by large menagerie owners such as the Krone, the Chipperfield, the Amar or the Bouglione, accelerated its transformation. The circus' mainly equestrian vocation must accept a combination of genres and the inevitable arrival of great wild animals acts. Split into a mosaic of attractions, the show nevertheless regains unity thanks to musical enchantments, of an exotic nature, called "circus operettas" by the successive directors of the Cirque d'Hiver, Gaston Desprez in the aftermath of the First World War, and the Bouglione Brothers from 1934 onwards. The nostalgia for the great historical epics resurfaces, particularly Ben-Hur and Buffalo Bill, allowing the deployment of a very diversified know-how of a universal equestrian tradition: free-riding cavalry, chariot races, Roman games, rodeo, stunts, cavalry charges and military parades. In a space where the horse is once again king.