by Marika Maymard

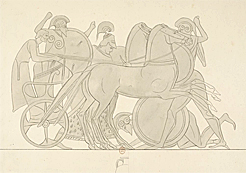

The white horses of Selene, goddess of the Moon, gallop on the frieze of the Parthenon, tense, vibrating, nostrils wide open in the race. They pull the silver chariot through the darkness, nestled in the light of the one who leads them. The bare marble does not reveal any bridle, cavesson, or even net. They freely share the mission of the star, a coupling united without hindrance in the same ardour.

The dream of every rider: to be one with his horse, a docile, fast and tireless extension, which gives him the same strength, confers upon him the same greatness.

The horse, our hero?

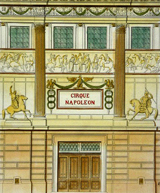

In fact, man knows what he needs in terms of patience, courage and attention to get the horse to come to him in confidence, accept to work wholeheartedly and finally, acknowledge his domination and surrender to his intentions. Then, he asks the artist to paint it, to sculpt it in all its beauty, with a quivering coat and mane or frozen in the wise and sophisticated pose that the education in war or parade has given it. The nostalgia for ancient games, which have been brought to modern-day circuses and hippodromes, has revived flat races, chariot races and equestrian exercises. As stone circuses, alternatives to ephemeral wooden and tarred canvas constructions, were built, they were decorated with mascarons, bas-reliefs or horse sculptures on their facades. Built under the direction of the architect Jacques-Ignace Hittorff, the Cirque de l'Impératrice in 1843 and the Cirque Napoléon at the end of 1852, are decorated with the paintings and bas-reliefs created by the sculptor James Pradier's studio, both inside and outside, in friezes. Equestrian statues frame or overlook the entrance porches, from Astley's first amphitheatre in London in 1770 all the way up to the monumental quadriga of the Djurgården circus, which opened in Stockholm in 1892.

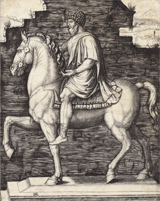

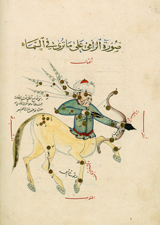

There are numerous equestrian cultures in the world, and there are many different dressage and riding methods, but everywhere representations of the horse, even free and bare, speak of the desire to capture and tame it. In the common history of man and horse since the end of the Paleolithic period, murals, medals and coins have documented its presence in our imagination and in daily life. Each era, each territory generates its own equestrian model. For nearly a millennium, the Etruscan civilisation has produced both representations of bare or harnessed horses, with an extremely refined aesthetic and the terracotta bas-relief of the Little Horses of Tarquinia, made famous by Marguerite Duras' eponymous novel. Majestic, colossal, the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, a peaceful Roman emperor imbued with Stoic philosophy of the 2nd century of our era, represented in a civilian costume, has survived the centuries without damage. Like other statues cast in bronze or carved in marble in honour of winners in chariot races, it provides information on the characteristics of an equestrian experience that has not yet been developed with certain forms of equipment, such as horse stirrups, for example.

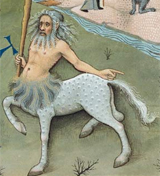

A fabulous animal, also winged, the mythical Pegasus, son of Jupiter, inspired playwrights of all time and, under Pablo Picasso's brush, became the central character of the curtain he painted for Parade, a ballet created by Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie in 1917 and set in the world of the circus. The Centaurs, the fruit of the union between Centauros and the riders of Magnesia, a half-man, half-horse creature, have the intelligence and reasoning ability of man and the skills of the horse. Alongside their historical background and the origins of their mythology, they generate a somewhat disparate genealogy of characters who appear, one during the Trojan War, to help the besieged Trojans, the other, like Nessos as Heracles' courier or like Chiron, of a more divine nature, as a benefactor. In the very real world of the circus, some riders and squires who are in perfect harmony with their horses, such as François Baucher or Ernest Molier, are regularly compared to Centaurs by contemporary chroniclers.

Curiously, circus culture has an originality that has long been stigmatised as marginal and naive, but it is nevertheless enriched by themes and characters that are widely present in cultural traditions and habits that are, admittedly, often revisited. Graphic arts produce images of horses trained in activities where man has always used them, such as transport, war, diplomacy, pleasure and a myriad of other forms of entertainment. Sovereigns have often exchanged gifts, and observers describe the number and richness of these gifts in great detail. Offering a trained horse, usually for war or jousting, engages both parties who both know how valuable it can be. The beauty, the docility but also the quality of the breed's blood, in other words its pedigree or thoroughbred origin, but above all the thrust without which the horse would not go far, are of the utmost importance. The equestrian culture of the Turks, or Ottomans, is very famous, both for the training of acrobats and riders in combat. Receiving a thoroughbred stallion prepared for confrontations coupled with an elegant and proud line for the parade is paradoxically a guarantee of peace and mutual trust.

Like the poet or storyteller, the painter celebrates the horse indiscriminately for some of its sought-after qualities, or for characteristics that man fails to tame. Thus, its power, multiplied tenfold by the violence of some of its outbursts or the refusal to let itself be dominated or controlled. Thus, the bellicose horses carried away by a fury that the riders painted by Horace Vernet in 1820, in a work entitled La Course des chevaux libres, are struggling to contain. The so-called skilled horse-riding style flourished significantly in the circus ring during the 19th century. By showcasing "free" horses and an even more advanced equestrian discipline, the haute école, man demonstrates a very specialised know-how in terms of education and respectful domination of the horse. The sophistication of the method, the contained thrusts and the fluidity of the sequences of figures in the dance of the squire with his horse completely revolutionise the image of the fiery steed involved in battles, wars, crusades or tournaments.

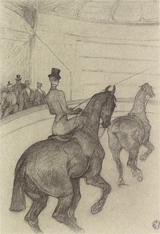

Less spectacular than the evolutions of the riders with panels in tulle skirts or the acrobats and jumpers standing on their horses, the riding exercises presented by strict amazons or a master squire in full garb with a top hat. Alfred de Dreux paints Elisa Petzold and Caroline Loyo. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec portrays Jenny de Rahden, a slender and dark horsewoman, Maks Kees, a Dutch painter from the early 20th century, paints dozens of paintings depicting Amazons and school squires who performed in the Cirque Carré d'Amsterdam, Jean and Marcelle Houcke, Thérèse Renz as the White Lady, the Carré brothers or Alex Konyot, the White Rider, amongst others.

War reigns over societies, either as an underlying theme or as incisive features. Picasso's gutted horse, a detail of his gigantic canvas Guernica, is a unique symbol of the injustice and suffering suffered by the most innocent of creatures, such as the dead child carried by his mother on the fresco that echoes the bombing of the city market on the 28th of April 1937. The language makes sense of the most significant episodes of history that poets grab a hold of. In his Iliad, Homer evokes the Trojan Horse filled with soldiers infiltrated to annihilate the last resistance of the Trojans. In familiar parlance, a Trojan Horse is that unstoppable ploy that will turn a situation around, or in computer language, malicious software that introduces a destructive virus. Another echo of a conflict situation, the frieze horse, a strategic rampart made of hardwood, iron or pointed stones, would recall an episode of the Eighty Years' War fought by the Spaniards against the Netherlands in 1568. Yet, majestic and vibrant in its black ebony coat, with its long moving mane, the real Frieze horse, or Frisian, blends on the circus rings with the immaculate Lipizzaner that looks all the barer. Almost facetious, the detours of the technical language of dressage call for less controlled human reactions. Thus, under the Roman Empire, the Latin word trepidium refers to the action of flexibly bending the knee by changing feet several times on the spot. This movement, useful to the mounted warrior to adapt to the war fields and the movements of other fighters, recalls a natural gait used by the male horse towards the female during the courtship. Worked on, it is at the base of the piaffe, that sophisticated haute école look that makes the rider and his horse dance together. Is it the effect of the constraint felt by the trainer in learning this movement or the impression of arrogance that the figure conveys? Over time, the term trepidium has evolved into "trepidation", just as the term "piaffer" is sometimes used to refer to a form of compulsive reflex caused by waiting or by irritation.

Some men may seem overly attentive to their favourite horses. A certain History relates the excesses of an unbridled passion embodied by the emperors Caligula for his horse Incitatus or Alexander the Great for his valiant steed Bucephalus. As a result, they built them a palace to live in during its lifetime, a city in its name, on the site of its death. On the Herbert Von Karajan Square in Salzburg, Austria, a Baroque style pool designed by Fischer Von Erlach was built in 1693 to provide the parade horses of the city's prince-archbishops with a swimming pool water trough – Pferdeschwemme. A statue of a foaming horse, held by a squire, erected in its centre in 1695 by Mändl, stands out against a background of frescoes of spirited, free horses by Ebner and Stradanus. There, Pegasus also appears victorious on Bellerophon. This grandiose tribute to horses and horse riding, which is part of the city's architecture, a territory eminently dedicated to humans, gives the animal an unparalleled identity and a special place in the city's history. Whoever shares the master's house throughout his life accompanies him after his death.

From one end of the world to the other, ancient funeral rituals associate civilians and the military mourning around the deceased. The representation of the decursios and the consecratios, funeral parades of priests, officers and notables on the pedestal of Antoninus Pius' column in Rome was reflected in the discovery of hundreds of clay soldiers, on foot or by horse, who emerged from the Xi'an graves, ordered in neat regiments in the mausoleum of the Chinese Emperor Qin.

Finally, far from the riders crowned with the glory of victories, an everlasting tradition enshrines the reputation of the Dalarna red horse, which was widely reported in the media through its presence at the 1939 New York World's Fair, where more than 10 000 small figures were in great demand. A beautiful symbol of the know-how of Swedish craftsmen and the gentle nature of the region, the manual production of the small toy, initially made in the 18th century by the loggers of the Dalarna forests, is perpetuated in the village of Nusnäs. The small wooden horse with its floral decoration is in harmony with the shimmers of the virtuoso watercolourist Anders Zorn and the discreet charm of the genre scenes by the painter Carl Larsson. All in simple curves, it barely awakens the deaf pounding of the Viking cavalry that underlie the Scandinavian attachment to the horse, as symbolised by Sleipnick, the eight-legged horse of the God Odin.