by Marika Maymard

The concept of the circus was created by Philip Astley 250 years ago through equestrian exhibitions. Characterised by its appearance in a round ring, the new "show" is described as modern in contrast to an ancient circus derived from Etruscan traditions and the Greek Olympic Games but developed by the Romans of the West in the Middle East. He borrows from this ancient memory a certain practice of horse training.

From ancient equestrian games to "learned" equitation

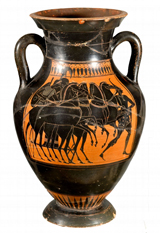

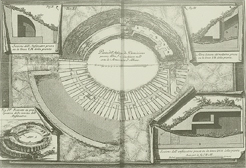

If acrobatics is a fundamental discipline that precedes the advent of the circus, the horse is the touchstone. Before a squire in the 18th century drew the ideal 13-metre circle where his horse would be able to perform, there was a gigantic place in ancient Rome called the "circus", which had been designed since the 6th century before the Christian era to accommodate equestrian games – Ludi circenses. Contrary to the generally accepted perception, the ancient circus is far from being round. Surrounded by stands designed to accommodate tens of thousands of spectators, it consists of a very elongated playing area. Riders or two – or four-horse-drawn chariots – the biges and quadrigas – turn at its extremity around a central promontory, the euripe, later called the spina, punctuated by an obelisk symbolising the Sun. Its circularity is there, in this 180-degree turn, the object of all the dangers for the teams hurtling at high speed. The Circus Maximus in Rome, built on the site where Etruscan kings already staged equestrian races before the reign of the Romans, measures in its most accomplished version nearly 600 m by 200 m and is dedicated to aerobatics virtuosos, the desultores, mounted races and chariot races. With a few rare exceptions, circus games do not include hunting – venationes –, gladiatorial fights – munera – or animal entertainment, mainly presented in the oval arena of the amphitheatres.

"Manager" is derived from the French word "manège"

Setting up a circus company requires a combination of skills, a solid team and some ambition. The first circus, curiously called an amphitheatre, was founded by a soldier who had made a name for himself in horse control. To enter civilian life when he left the army, young Philip Astley gathered and organised elements identified in the observation of certain horse vaulters with whom he joined. The Johnson, Sampson, Price or Conningham train in nearby entertainment venues, the Three Hats Cabaret or the Dobney's Gardens' Bowling-Green in Islington1. Astley developed a sense of showmanship that inspired him to combine acrobatic performances and comic interludes with his equestrian exercises. The formula was successful and throughout the 19th century, squires built a vast network of circus establishments, from the English John Bill Ricketts in Philadelphia in 1793 and the Austrian Christoph de Bach in 1808 in Vienna, to Giuseppe Chiarini who arrived in Japan in 1886 after building establishments as far away as Australia. Founder of a dynasty of riders in France, Antonio Franconi inscribed the name of Cirque Olympique on the pediment of his establishment in Mont Thabor in 1807. Soon, the acrobatic and horse-dancing exercises that made the reputation of the riders and standing riders must coexist with a new form of horse-riding, presented at the Cirque Olympique des Champs-Élysées in 1835 by Laurent Franconi and especially its founder, François Baucher.

Profession or vocation

Horse training involves a very precise and extensive deployment of techniques and vocabulary where the relational dimension between the master and the horse is of paramount importance. Some speak of equestrian science, others of equestrian art, all notions that evoke a technicality, knowledge and a high standard of excellence that leave no room for improvisation, only perhaps for intuition. In times of conquest, warrior peoples steal the secrets of the training methods and aids that guarantee the success of the opponent. Thus, the Romans were interested in Gallic techniques, such as the horseshoeing of hooves and the use of stirrups and involved them in particular in the operation of the factions organised around the competing teams of charioteers.

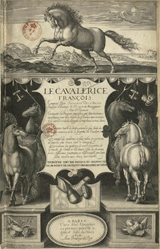

Since the guide of Xenophon, philosopher and military leader of the 4th century before our era, De l’équitation, the authors of equestrian treaties have drawn the outlines of a dressage training program that targets in parallel the comfort of the rider, an optimisation of the animal's faculties according to its use, and the care to be provided to ensure good performance and maximum endurance. During the Renaissance, the first equestrian academies emerged, namely the one created in Naples in 1532 by Federico Grisone and the one opened in Ferrara by Cesare Fiaschi. These pioneers and their disciples, Gianbattista Pignatelli, Salomon de La Broue, Antoine Pluvinel, defined and perfected the various stages of training. They prioritise the gestures and behaviours to be respected in order to gently control and balance the horse.

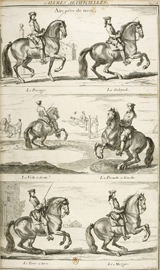

Removed from its natural and highly codified group, the horse needs to see in its master, who dominates it, a protector. The fear of a steed dropped in the midst of the clash of weapons, screams and crowd movements must be overcome to make it a stimulant that will allow it to advance on the obstacle. A good education should be based on the horse's natural gaits and behaviours in order to gradually teach it more sophisticated figures. Learning dodges and attacks, progressing up and down the hill, jumping with or without obstacles, transitioning to different gaits, group walking for the parade are all factors that interest both the soldier and the squire on an acrobatic ride.

The Spanish School of Vienna, founded in 1565, is the oldest riding school in the world still in operation. It owes its identity to the horses it promotes, the lipizzans, initially originating from Iberian lines. The learning and training methods are inherited from the writings of the French squire François Robichon de la Guérinière, notably the École de Cavalerie published in Paris in 1729-1730. The purpose of these training protocols is above all to strengthen the horse to give it more strength in combat, but the movements, unused during the engagements, remain spectacular. They will be the foundation of the haute école register and become a magnificent pretext for artistic performances.

Royal Squires and Professor to the Empress

The practice of dressage is built on a base made up of specific codes and language that feed a real culture qualified as equestrian or equine depending on the environment. Equitation, a noble discipline, has been considered throughout the centuries as a matter for a king, knight, warlord or military school. No one messes around with the welfare of the elite. However, the circus, in its spectacular dimension, is suspected of abusively diverting the art of training and riding horses to push the limits of prowess. Despite their reputation for their skills, Laurent Franconi, first school squire at the circus, teaches horse riding to Eugène de Beauharnais and his son Victor... to the Bourbons. James Fillis (1834-1913), trained by François Caron, faithful to Baucher, was appointed chief squire of Tsar Nicholas II's cavalry school. Theodore Rancy, who built nearly two hundred circuses in Belgium, France and Switzerland, welcomed the Khedive Ismail Pasha for the inauguration of the Suez Canal in 1869. Pauline Cuzent, who trains her horses herself, teaches in the courts of Europe. Empress Elizabeth of Austria offers Elisa Petzold the thoroughbred Lord Byron in exchange for her lessons. The baucherism once disparaged in the ranks of officers is now inspiring cavalry schools, including the Cadre Noir de Saumur, founded at the end of the 16th century. Master riders banquistes Alexis Grüss and his cousin Lucien Grüss are invited as guests of honour to this same prestigious school, while Fredy Knie senior lent his support to the Vienna School to make resistant lipizzans piaffe...

Back to the days of excess in Antiquity

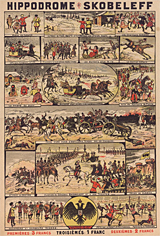

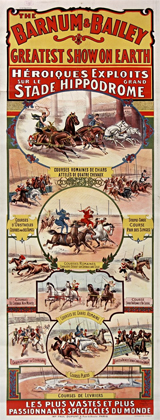

The desire to achieve spectacular feats, synonymous with triumphs, is no longer driven by paying homage to the gods or an ode to earthly potentate, but by the reeling of the honours of an ever-growing public. Porous, the world of entertainment is permeated and nourished by the initiatives and trends of the times. The 19th century was marked by generally disastrous military campaigns, advantageous colonial conquests and exponential scientific, technological and industrial development that profoundly changed the Western economy. The project to promote on a large scale the products of colonial progress and expansion hastened the scheduling of major world exhibitions. Their opening generates a large number of visitors, a potential windfall for entertainment entrepreneurs. The enthusiasm for horse-related activities is not slowing down, on the contrary. The selected English horse breedings are the envy of military staffs anxious to renew unsuitable cavalry. Governments see an opportunity to create a new economy based on horse breeding and build riding arenas and stud farms. The equestrian circus is both a provider of instructors and a perfect sounding board for any innovation in the world of equestrianism. In Paris, Lyon, Vienna, Berlin or London, racecourses were built where, sweeping twenty-five centuries of equestrian practices to the side, the directors programmed a jumble of Roman chariot races, presentations without restriction, steeple-chases, fox hunts, carousels, amazon races and historical pantomimes parades.

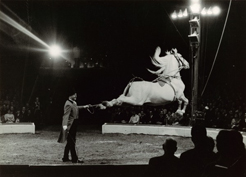

Cavalries and carousels

In the 20th century, canvas hippodromes, built in the American style in four to eight masts in a row, produced numerous multi-faceted attractions in the gigantic arena. Led by mounted riders or master riders on foot, American circuses regularly present sumptuous equestrian displays where free cavalries flawlessly arranged on the three tracks simultaneously perform at the same time. These enterprising presentations are given by squires and trainers, often from Central Europe. They bring with them the mastery of a unique style and give the great American cavalries under their command an extraordinary appearance. William Heyer, Rudy Rudynoff, Jorgan Christiansen, Charles Mroczkowski or Arthur Konyot with his Percherons, bring a very European elegance to their trained horses in the sometimes somewhat chaotic context of the American circus. A notion that a school horsewoman like Claude Valoise magnifies when she is the central figure of Après-midi au Bois, a pretext to justify a sumptuous deployment of riders, carriages and phaetons, to create both the quintessence of academic equitation and the flamboyance of the great equestrian shows that prevailed in the previous century.

On the other side of the Atlantic, trainers like Alfred Petoletti with the mixed group of eight trakehners and eight sorrels from Carl Hagenbeck, Franz Althoff, Helmut Rudat, Fredy Knie or Carl Sembach revisit the magic of the great carousels, giving them a magnificent identity. The Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art was founded in 1973 under the initiative of Don Alvaro Domecq Romero. Its aim is to promote equestrian art and equine breeding and regularly offers historical shows.

From one end of the circus history to the other, spectacular forms respond to each other. But in the horse's particular world, the quality requirements that govern performance are such that initiatives are becoming rare despite a renewed public interest in horseback riding. The future lies in the continuation of a quasi-academic work carried on in the circus by the Grüss and Houcke families in France, the Casartelli in Italy or the Knie in Switzerland and by Bartabas, within the Académie équestre nationale du Domaine de Versailles, heir to the learned horseback riding school founded in 1680 by Louis XIV.

1. See The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction, published by J. Limbird, London, 1839, vol. 34, p. 108-109.