by Marika Maymard

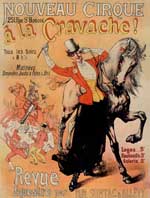

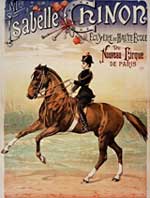

If the amazons, haute école horsewomen who appeared in the 19th century, share something with the mythical Amazons, fierce warriors in Antiquity, it is the desire for freedom, will and pride rather than the practice of riding, since according to Philostratus, the latter were fighting on foot. Their common ground is a passionate and courageous investment in activities reserved for men, without disavowing the qualities and advantages of their femininity. Even more than other women of action, the horsewomen have undoubtedly inherited the term from the mouth of a half mocking, half admiring observer when such a horse huntress rides a horse sitting on its side, continuing her race with obstinacy despite the falls, as the authors of Cavalières Amazones, une histoire singulière, suggests [Swan 2016]. It was in the middle of the 19th century that the contours of the modern Amazon were drawn. The strong ambition of the new female riders, the complicity of men, pioneers of a new equitation and the opening of an entertainment market in a landscape where the modern circus fits in advantageously, contribute to the development and public recognition of a difficult discipline, the haute école, born in a male universe reserved for the elites.

A special seating position

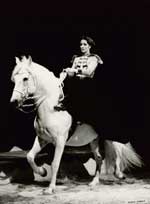

Side-saddle riding is obviously not just about riding fearlessly. But it took a lot of determination on the part of the first "seated" riders to develop the conditions of a practice that was reserved, until the Renaissance, when they were able to go for a stroll or a hunting trip, with a falcon or a sparrowhawk on their hands, at the quiet pace of a hackney ambling along. In some eras, the horsewoman sits sideways on a sambue, a mat on the horse's back, wedged in a padded sack or perched on a saddle with only one fork, her back resting against a wooden plate or an iron rail. She cannot ride a mount by herself, whose head and shoulders she can only see with a wiggle that cannot be held. Her autonomy depends on her complete control of the horse and therefore a complete redesign of the saddle, involving its material, its shape, the number and position of the forks installed on the pommel and designed to hold the legs with the addition of a long stirrup for the left leg. Once the risk of an accidental rise of the left leg under the jerks of the jumps and all the raised airs (ballottade, levade, cabrade...) has been eliminated, the practice of the haute école can now be extended to side-saddle riders. She still has to adjust the details of a costume deliberately cut in a sober and elegant way and above all, the height, cut and density of the long skirt which must not hinder the foot and must resist the wind of the race. The costume of the horsewoman is called... "an amazon".

Top of the bill

When Caroline Loyo stepped through the porch of the Cirque Olympique on Boulevard du Temple in 1833, her horse in a bridle, she was seventeen years old. She comes from Moselle and wants to learn how to train the horses she wants to ride. A student of Jules Pellier guided by Laurent Franconi, a reference in the uncompromising circles of French equitation, she became the first amazon, a school horsewoman at the circus. In the ring of the Cirque des Champs-Élysées opened in 1835, Pauline Cuzent, also trained by Pellier and Baucher, Caroline Loyo, Antoinette Cuzent-Lejars, teamed together in manoeuvres and quadrilles compete in speed and virtuosity in haute école exercises. Transcending the teaching received, both these and others, such as Elvira Guerra, Adèle Drouin, Elisa Petzold, Constance Chiarini, Clothilde and Émilie Loisset, contribute to the promotion and development of the school repertoire, as far as Scandinavia and from there into Russia, during tours where they perform. Some teach in the different courts of Europe, and meet other amazon horsewomen, daughters of founders of big companies or on the contrary from the aristocracy or the great bourgeoisie, mirrors of the different riding schools.

In the 20th century, the school riders, following Katja Schumann or Maud and Gipsy Grüss, on the one hand, and Sabine Rancy, Yasmine Smart or Géraldine Knie, on the other hand, were divided between side-saddle riding, more aristocratic, and traditional, more dynamic riding, astride like men. With the same high standards.