by Marika Maymard

In his relationship with the horse, man develops a process of taming, domestication and instruction, which restricts, or at least shapes, to a certain extent the horse's activity, personality and entire life. In keeping with its ideal of pure performance, the vocabulary of the circus can also sometimes betray our common sense. In other words, what really remains of the meaning of the word "liberty" in a representation, certainly unfettered, but where the animals obey and follow a sequence of figures and passages?

"When it comes to liberty dressage, a special education for circuses, it is not the intelligence of the horse that is the main factor, but the skill and ingenuity of the man that must be admired; for he takes advantage of the horse's natural dispositions and an instinctive domesticity." Jules Pellier, Le Langage équestre, 1889

A cavalry for the circus

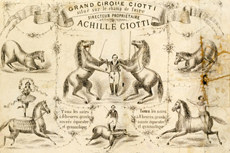

Long before the invention of the modern circus, the horse lost its status as a wild animal. Detached from the original group, it joins, according to the needs of the rider, the charioteer or the warrior, a house, a stable or a cavalry. A man who rides a horse knows this: the more he lets his horse bridle on its neck, on the field or on a stroll, and the less likely he is to get his horse to accept the constraint of the exercise. So, what does the term "liberty" mean for the circus horse? The answer is simple: a horse that is presented at liberty moves without a rider, under the direction of a master rider on foot or sometimes on horseback. Particularly highlighted for its beauty, ardour or grace, it can evolve alone in the ring and appear under its own name in the programme alongside its master, like a pair of partners. It is often displayed bare, equipped with false reins or even a simple invisible net that is used to place the horse's head and the riders of the gate, to grab it, or quite the opposite, with saddle, harness and feathers.

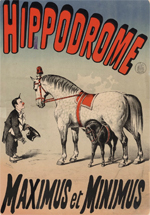

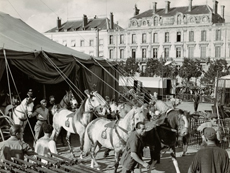

The horses at liberty belong to the same species, white Lipizzans, golden palominos, dark Russian horses, black ebony Friesians. The term "Liberty" is often followed by the name of the master squire in the advertisements and announcements: The Liberty of Alexis Gruss, William Heyer, Georges Loyal, Albert Carré, Jules Glasner or Henry Rancy. Gradually, women took over their fathers' or husbands' stockwhip at the same time as the direction of the circus, such as Eugénie Martinetti-Farina, Tilly Rancy, Paula or Micaela Busch, Frieda Krone or Christel Sembach. They learn the trade in the family melting pot, like Sabine Rancy, Carola Althoff-Williams, Silvia Zerbini, Suzanna Svenson or Yasmine Smart, and make their horses twirl and stand up in evening dresses. There are several unusual attractions to enhance the show: a cavalry of Falabellas, some zebras, a Mini-Maxi or the participation of one or two elephants.

The race for Liberty

Like other European capitals, Paris saw the construction of several racecourses between 1845 and 1905, pretexts for games and pantomimes with big shows. Cavalries are used as arguments for historical or military reviews, but they also perform at liberty on custom-made tracks. Even in this gigantic and noisy setting, riders from renowned families lead specially trained horses with overall movements and familiar gaits, attentive to the voice and promise of reward of their protector. But the immensity of the exhibition space means that groups of barely broke horses can be exhibited, offering flat races or show jumping at liberty, in other words without riders and without constraints. Finally, in the 20th century, great entrepreneurs from Europe and America revisited the tradition of "Liberties" presented on three tracks at the same time or on a racecourse track, in giant marquees like Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus (1918-2017) and, for a long time, most American circuses: Krone (1924), Barnum's Circus of the Court brothers and Pierre Périé (1928), American Parade of the Bouglione (1981), Il Circo Americano of the Togni (since 1963), Chipperfield (1946-1955), Gleich (from 1928 to 1933) or Kludsky. Specific to circus performances, these liberties extend and complete the range of "academic" dressage, whose future is uncertain outside family companies.