by Pascal Jacob

One of the major issues of the circus lies in its obsession with movement, stemming from the circular dynamic of the space and the omnipresence of the horse from the early days of the form. The organic nature of the performance is based on movement, i.e. the hyper-mobility of horses and men, and of the structures needed to help the various sequences in the show move along smoothly. By inserting the notion of ebb and flow to illustrate the permanent entrances and exits of the material attached to the most of the acts, it became clear that mastering mobility was a determining factor in terms of the rhythm and fluidity of the sequences.

This global mobility is evoked in the implantation of a certain number of apparatus created to amplify the effects of an acrobatic performance. The elements linked to the horse are obviously the first devices designed by artists who sought very early on to diversity their practice and invent extensions supported by, or linked to, their animals.

The finest mobile apparatus, and probably the most astonishing one ever, was a wooden platform assembled on 27 December 17861 to create a moving stage for six horseback acrobats, in response to accusations of unfair competition from Sieur Nicolet, patron of the Théâtre des Grands Danseurs et Sauteurs du Roy and open rival of Philip Astley, who was then ready to conquer Paris with his horses and circus riders. The aim of the subterfuge was to destroy Nicolet's protests, which were motivated by the presence of acrobats in the rival company, and thereby present all the exercises announced by Astley, as the ruling stipulates, "on horseback."

No doubt the panneau, a thick wooden saddle covered with leather invented by James Morton and made popular in 1849, was somewhat heir to this heavy stage created in response to the demands of censure and the privileges granted to some performance spaces. But it also functioned as a mini stage, on which the circus rider, dressed in a frothy tutu, performed an entire ballet in the space of a few minutes, unless she was sharing the panneau with a partner for a romantic pas de deux inspired by a choreographed fantasy.

Forms and transformations

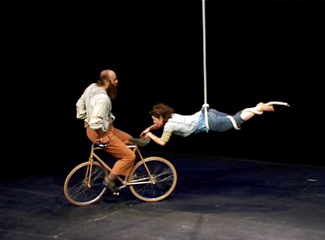

Mobility in the ring is therefore conditioned by the horse. The animal, considered more of a partner, is the starting point for developing the first codes of performance. But above all, it is because he trots, gallops and clears obstacles that the performance space is circular, and that the phenomenon of attraction develops from an axis or central point around which everything else is organised. This original equestrian mobility gave rise to a certain taste for apparatus with the potential, in some way, to become a substitute for horses. The invention of moving devices such as the balance bike, the penny farthing or the velocipede, was a decisive factor for numerous acrobats who saw these innovations as a means to enrich their practice, to capitalise on their physical qualities and – an essential for a show that always wanted to be more popular – to be in fashion and up to date. This quest has been recurrent since the end of the 19th century, and the circus happily combines tradition and modernity in its dramatic registers. Every variant imaginable from the bicycle, tandem or unicycle, is ideally established in the axis of the ring, and some companies even model their development on the equestrian repertory, creating both a distancing effect for the original model and a slight confusion in reading the original parameters. To enable cyclists to work, they need a stable, smooth platform, in formal contradiction to the blend of soil and sawdust that ensured the soft floor necessary for horses' hooves as well as for acrobatic landings. Music hall and theatre stages provided cyclists with a better-adapted space for their development, but in 1886, the New Circus introduced a revolutionary innovation by substituting a coconut mat for the usual flooring, and this was simultaneous with the beginning of the decline in the equestrian art, opening the way for the development of new techniques and encouraging their integration into the ring.

New apparatus

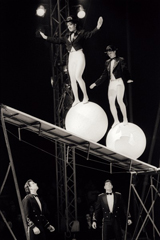

This new surface made things easier for numerous disciplines, and apart from possessing flexible qualities similar to the original floor blend, enables free ladder, acrobatic bike and balance ball artists to express themselves more easily. In addition, its smooth surface facilitated the occasional installation of floorboards, an indispensable structure for work on several new apparatus such as the German wheel, invented in the early 1920s, the Cyr wheel, the Zig or the Topka, innovative devices, invented from the 1990s, which generated movement and were grounds for new stage writing. The principle of an apparatus that defines forms, conceived as a stylistic argument and generator of technical transformations blossomed mainly in the Soviet Union in the 1960s. There, a bureau of engineers was attached to the central state circus organisation and continually questioned the notions of space, structure and material. It also addressed the simplification of putting up and taking down apparatus, as well as the creation of new acrobatic supports such as rockets, aeroplanes and spectacular wheels of death – devices hung from the cupola which provided modern grounds for new aerial feats.

Playwrights and technicians also questioned everything that conditions the fluidity of a sequence, the consequence of notions of rhythm and harmony in the performance. Motorized devices were to be decisive in research marked by the implementation of pure innovations. In addition, integrating invisibility in the appearance and disappearance of the apparatus became a major issue in the development of a show. This desire for the absence of effort when implementing and setting up material was fully resolved in Aurélien Bory's Sans objet show, where an impressive robot hidden by a plastic membrane came to life at his programmer's command. His "mechanically" choreographed movements were also dazzling grounds for very human balancing acts, adapted to the movements of a stage object, which had become, eventually, a mobile apparatus.

1. See The Memoirs of J. Decastro, Londres, Sherwood, Jones & Co, 1824. Print reproduced opposite page 44.