by Pascal Jacob

The circus has always shown an extraordinary aptitude for integrating the most notable inventions and innovations throughout its entire history. Designed and developed in the second half of the 19th century, mainly by the Frenchmen Pierre and Ernest Michaux in 1861, the bicycle, from the first velocipede to the balance bike, invented in 1817, and from the penny-farthing to the popular "bike," very quickly joined the circus repertoire, and technical developments encouraged artists to develop and increase the complexity of the language linked to this new "apparatus." This novel form evoked, in a small way, an amused echo of the dynamic of the equestrian acts in the circus ring. This aspect was displayed by an acrobatic company from Shanghai, who had a group number in their repertoire, in which four couples of young girls multiplied jumps from one bicycle to another, landing on shoulders, and performing figures largely inspired by Cossack acrobatics.

Trends and transformations

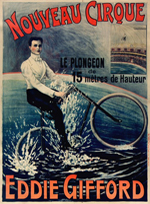

From 1880 onwards, the technical evolution of this method of transport destined to a brilliant future provided more and more possibilities in terms of flexibility and speed. As the acrobats mastered it, it opened the way for an ever-richer repertoire. Very soon, the first companies appeared, encouraged by the fashion for variety and music hall shows. These two forms were similar to the circus, but had wooden stages with smoother, safer boards than those used under the big top tents or in permanent circuses, which were put up for the occasion between the horseback performances and the clown numbers. As the bicycle allowed for speed and acceleration, certain daredevils would ride off the top of a springboard that could be tens of metres high, or ride around and around a bottomless wooden funnel, suspended over a void, or around a cage filled with wild animals, and so on…

At the end of the 19th century, the bicycle was in fashion and the circus jumped on the bandwagon. The Ancillotti company adapted horseback work to this new apparatus, which the monarch of a distant Asian kingdom had chosen, instead of horses, when equipping his army. This family company, one of the best of its time, was exceptionally skilful. Head-to-head balancing acts, shoulder-to-shoulder somersaults and two- or three-man columns characterised their repertoire, making them a prized attraction. Audiences were as fascinated by the feats accomplished on this everyday object, as the very first spectators had been with the circus riders' exercises a century earlier.

From group work to solo act

Given that the bicycle is an everyday object, artists and producers attempt to outdo each other in ingenuity when adding the discipline to their shows. Some animals love speed, and for certain soviet trainers, there was a great temptation to train bears and monkeys to mount a bicycle and combine pedalling with speed. The German, Gerhard Kaiser, trained an elephant to sit on a tricycle and ride around the ring, an exercise that had already been done at the end of the 19th century by trainers from the Hagenbeck firm. Acrobatic bicycle riding gradually became a more individual act and many solo or duo numbers helped to make mobile apparatus popular, and to enrich the technical language of the form: wheelies, skidding, hand balancing and pirouettes constitute a framework of numbers often devised as playlets in which the cyclist's skill is emphasised by a costume and a painted backdrop when performing in a theatre. Harry French, Nick Kaufmann, Dan Canary and Joe Jackson personify this appropriation of the bicycle, often used for work based on characters identified by their appearance and body language. The name of Lilly Yokoi will no doubt go down in history as one of the most extraordinary bicycle acrobats, who began work in 1962 on a gold-plated bicycle and performed in the most prestigious circus and music halls in the world.

Technical developments

Although the first bicycle acts gave pride of place to the new machines coming out of the factories that were springing up to answer the ever-growing demand, gradually, nostalgia and the quest for difference saw acrobats using older models such as the penny-farthing and the balance bike. In addition, they created technical jokes such as minuscule bicycles a few centimetres tall. Tanzanian Baraka Jima Fermouz ended his number perched on a miniature unicycle, having played with improbable constructions of several wheels piled up, or "giraffes" of several metres high. BMX racing, which became an Olympic sport in 2003, began in the 1970s on dirt tracks in California, where teenagers raced on sturdy bikes, mainly the Schwinn Sting-Ray. The BMX bike has made regular incursions into the circus ring, in a variation on the acrobatic bicycle as practised by Chinese companies since the 1950s, or by solo artists, such as Serge Huercio. Trained at the Centre National des Arts du Cirque in Châlons-en-Champagne, the latter created both a character and a flowing succession of feats carried out with a glimmer of humour.

Acrobatic variations

Tightrope and highwire walkers have at times incorporated a bicycle or unicycle into their balancing feats. The Chinese slackwire artists Zhang Fang and Li Wei, as well as the Ukrainian Andrei Ivakhienko, favour a unicycle driven by arm-power, whereas the highwire walkers of the Quiros company use two bicycles linked by a pole attached to the shoulders of the pushers. On this pole a third acrobat balances on a chair… This exercise was made popular by the Wallenda company in the 1930s, who performed it sometimes tens of metres above the ground.

The idea of the bicycle inspired a new level of creation, and tricycles, unicycles and monowheels were all used for enriching numbers and as material for sequences. For example, Diana Alechenko and Yuri Chavro created a romantic interlude based on a remarkable new technique. Then in 2015 in a more theatrical vein, but maintaining acrobatic standards, Ronan Duée and Dorian Lechaux, trained at the Montreal National Circus School, created a hand-to-hand unicycle duo that demanded incredible technical skill, combined with a spot-on scenario and acting. Beyond demonstrating agility, the apparatus has shown itself as a source of meaning and suggests new identification codes. When the Philébule enters the circus ring it produces a powerful mise-en-abyme of the organic form that is all-encompassing: two gigantic wheels, linked by a complex mechanism, act as a vertical, moving mirror of the circus ring that hosts them. The Philébulistes, who are movement creators, extrapolate the German wheel and the Cyr wheel, blending circular range with the Russian cradle, breaking another barrier in the use of the circus playground.

Interviews