by Pascal Jacob

The circus is the horse's finest triumph.

According to recent archaeological discoveries, mainly of small statues and a few large sculptures found in Saudi Arabia, it would seem that the domestication date of the horse needs re-assessing. Until now, the presence of this animal around men was evoked around 6,000 years ago, in a region of the world that today corresponds to Ukraine. From now on, we have to count closer to 7,000 years before our era, or in other words, man and horse have been close for 90 centuries, in the Middle East. This precedence speaks of even more complicity between two creatures of the same kingdom, but accredits above all, the place of the horse as a partner of every major development of humanity. Draught horse or warhorse, the animal has seen every transformation, from the utilitarian and the vital, through to the show register.

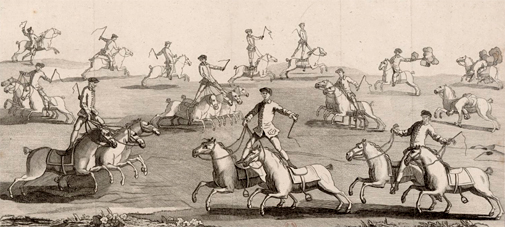

Warrior practices constitute a first source of inspiration for developing an equestrian repertoire provided for the curiosity of a large number of people. Combat techniques shared by horsemen, whether those who inhabited the Central Asian Steppe, or the First Nations of the great North American plains, form an intuitive base for line acrobatics, identified in the Caucasus under the name of Djiguitovka. An equestrian art originally practiced by Cossacks from Terek and Kouban, it was taught to every man without exception, and very soon became grounds for competition. Jumping off and remounting the horse, picking up small objects without unbalancing one's galloping mount by bending down only at the last second, standing up and bearing arms, as well as sliding under the stomach or the neck of the horse are classical "figures," also shared by Comanche Sioux, Mongol, and Ossetian riders.

Transpositions

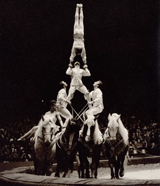

These vital and spectacular feats helped to formalise the equestrian acrobatics repertoire transplanted into the circus ring from the 18th century onward. Two centuries later, from 1965, the Moscow Gonka, a company composed mainly of horsemen, notably the Zapashnys and their horse pyramids, heralded mono-disciplinary shows that would develop twenty, thirty or forty years later with the creation in particular of Circo Zingaro, Théâtre du Centaure, Luna Caballera, PferdePalast, Cheval Théâtre and Cavalia.

The horse is the raison d’être for the ring and the circus.

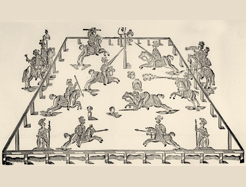

In order to encourage standing balances, jumps and acrobatics that the diameter of the "playground" was gradually determined, becoming standard in 1779. The primordial performance axis of the 13-metre circle submitted the figure abandoned in its centre to an extreme vision. The famous 360° meant that the rider's back had to be as expressive as his face, in a complex game of heads and tails that was based on the three-dimensional circus. The frontal rapport did not lead to the same causes or the same stakes, and the fact of turning continually, around the ring and oneself, represented an additional constraint, but was also a formidable performance convention that belonged only to the circus.

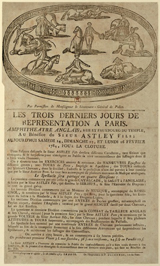

The twists and turns of history are sometimes cruel. The name of Philip Astley alone seems to have been remembered across the passage of time. The son of a cabinetmaker, trainer of difficult horses and demobilised officer was barely a quarter of a century in age. However, he was not the first, when in 1786 he chose to fence in a circular performance space on a plot of land close to the Thames in Lambeth, a London suburb, to perform on his gorse to the beat of a drum. Riders such as Johnson, Wolton, Bates, Hyam, Price, and Simpson had also presented equestrian exhibitions in a field or a market place before an audience astonished by such audacity.

Some of them, such as Johnson, had already worked in a circular space ten years prior and had sometimes, like Wolton, incorporated other attractions into their horseback exercises a few months before Astley's initiative. But most of these riders' careers were short-lived. Philip Astley was the first to organise his activity as a veritable show entrepreneur when he decided to protect his exhibitions by a wooden fence and oblige the audience to pay for right of entry to watch. Gradually, he combined circus with theatre, opera, and ballet by constructing its own building: the first permanent circus in which equestrian and acrobatic shows were performed in a 13-metre diameter circular ring, was built in London in 1779. The length of its radius – six metres fifty – was defined by the length of the schooling whip, an indispensable accessory for riders to regulate the pace of the horses.

Incarnations

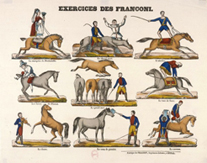

If we admit that the circus started on horseback, that also means that the rider has a role to play in the organization of the performance. By standing upright on a galloping horse, Philip Astley and all his followers crafted a powerful model that founded the spectacular register of the modern circus. The frogging worn by the hussars or the dragoons is a metaphor for the human skeleton, a symbolic ossification aimed at scaring the enemy when the sun made the gold or silver embroidery on the cavalrymen's torsos sparkle. As an officer in uniform, Astley thereby suggested an early visual outline that was often recycled throughout the centuries. But, paradoxically, the riders would rapidly abandon uniform in favour of more suggestive costumes, which were more closely linked to their propos. Although the exercises that structured the equestrian repertoire gradually became stable, the riders' imaginations had no limits. Andrew Ducrow was endlessly creative in illustrating his horseback exercises, taking inspiration from the gravediggers' scene in Hamlet to create the Flying wardrobe or using travellers' descriptions for the Indian Hunter number. The same level of diversity is perceptible in prints of the time that elegantly reproduce the refined costumes aimed at entertaining the audience and suggesting a different context each time. The feats resembled each other, but in this situation, it really was the costume that "made the character." The conquest of Egypt offered a colourful and flexible visual repertoire that enabled all interpretations. From baggy trousers to scarves knotted around waists, short jackets and embroidered, braided boleros. A series of prints based on equestrian exercises performed at the Cirque Olympique is a good illustration of this taste for Orientalism and confirms the significant slide towards diverse performances.

Echoes

Appropriation in terms of the circus was to become second nature. Classical ballet added its contribution in 1832 with Maria Taglioni's creation of The Sylphid, a ballet that imposed a costume that was promised a brilliant future: a tight-fitting bustier and a long frothy skirt made of light, transparent mousseline, set over a crepe petticoat – the romantic tutu. It was indeed a combination of ballet and circus, offering an image that was both strong and dynamic, and capable of integrating the imbalance of the rider and assimilating them to the grace of the ballerina. When it was adapted for the ring, the intrigue was seriously reduced and above all, the exercise tool place on a thick wooden saddle, known as the panneau. This was a veritable mini stage that moved constantly, enabling the horseback rider to take up classical postures until then reserved for ballerinas alone. More specifically, the recuperation of a fashion phenomenon was witnessed, and the issue was of some importance judging by Balzac's admiring witticism that saw him rename the riders Taglioni équestres. The imitation of a classical figure transcended and renewed thereby managed to create a link between two spectacular disciplines, which although neighbours in terms of the shared obligations of elegance and posture, are no longer so easily assimilated today. However, even though it is rare to see them in the ring these days, the panneau rider still wears a tutu. Sometimes, the fragile veil of the original is transformed into a decidedly more modern outfit, accumulating, just like ballerinas again, layers of tulle in classical white, or sometimes in delicate pastel shades in order to stand out.

From the press to the ring

This desire for identification was confirmed at an even earlier stage when a news story was used in a horseback scene, which rapidly became a standard and was performed around the world. The scene was set in 1768, and Philip Astley offered curious onlookers an equestrian fantasy drawn from a newspaper of the time. An election on a county close to London put forward a candidate disowned by the House of Commons and the government. The man, named Wilkes, opposed a reputedly powerful government, and the voters followed his adventures in the daily press. Now the plot thickens, as a tailor, encouraged by the candidate's bravery, and wanting to support him, decided to journey to his county, and this, on horseback. Now, in late 18th century English society, tailors had a reputation of being terrible horsemen. And Astley's audience were perfectly well aware of that. The success of the parody was such that it spawned copies in other rings, under various names, such as the Tailor's race, or Rognolet et Passe-Carreau, which were just as successful as the original. The costume was easily recognisable by an audience in search of something easily identifiable. It probably looked a little more patched together than usual, perhaps even a little more colourful, but then tailors had a reputation for making their own clothes from leftover bits from their clients' outfits. One could detect a strange, but apparently unrelated relic of the harlequin's propensity for using pieces of fabric to patch up or enliven his livery, victim as he was of his master's avarice. At the end of the day, the costume structure mattered, in being relatively accurate in terms of reality, far amore than any average adaptation, then deprived of its unique but essential meaning. Despite some embellishment, it was a real tailor who fell from his horse, provoking laughter. From this simple yet efficient element, a clownish comedy developed that was rich in multiple characters and became a key part of the classical circus show. Introduced five years later in America, the scene enjoyed considerable success, and new adaptations confirmed its popularity. In 1787, the now traditional Tailor of Brentford became The Taylor Humorously Riding to New-York.

Scripting the circus

With the creation of elaborate "ring scenes" such as Raphaël's Dream, The Flying Wardrobe and, above all, the Courier of Saint-Petersburg, riders, and in particular the British rider Andrew Ducrow, became famous far beyond the borders of their respective countries. The costume choice was a way of telling a story through a few positions, and a few rare decorative elements could evoke a different country or illustrate a mythological reference. An act such as the Courier of Saint-Petersburg was a perfect example of this game of correspondences. Created in London in 1827 by Andrew Ducrow, the exercise saw the rider stand up on two horses, one foot on each holding sufficiently far apart to enable other horses to pass beneath this improvised human bridge. Long reins lay across the backs of all the horses, and the rider would seize them as he passed, unwinding in time with the galloping horses, creating a virtual harness pulling an imaginary stagecoach. Above all it was a genuine physical feat, as the tension caused by the nine lead horses galloping was very strong, and it was extremely difficult to stand up on two other horses who would instinctively move away from each other when a third slipped between them. Once the technical aspects of the exploit were mastered, any decorative fantasy was possible, and although the occasional hint of exoticism appeared, with the Pasha's Escape for example, it was more about dressing the rider to provide him some slight theatrical identity during his time in the ring. The structure of the number was very simple, but corresponded perfectly to the rider's desire to add a "theatrical" and symbolic connotation to his act. In Ducrow's actual creation in 1827, small flags placed on the horses represented the different countries crossed and, floating to the rhythm of the horses' feet, they told the story of the journey themselves.

Imitated and adapted, this now classical number was known under different names depending on different nations and regimes. From the fine impartial Courier of Saint Petersburg to the Royal Post, but also the Imperial or National Post, as well as the Pasha's Escape and Longjumeau's Postilion. Theatrical and omnipresent in the city as a draught, school, or warhorse, the horse's supremacy is echoed in the circus in a daily life constructed around the animal and his aptitude to serve man. However, defeated by the industrial revolution that took off at the end of the 19th century, it gradually disappeared from the landscape and has generally disappeared entirely apart from in the peripheral domains of sport, leisure, and entertainment.

Performance developments

The importance of equestrian art has diminished considerably in the circus context and is more often than not a free, or an haute école performance. Although some riders still favour the dark coloured military tunic, from the end of the Second World War onward, fantasy was the flavour of the day. In 1958, the Schumanns performed at the Olympia in London at Bertram Mills. Paulina was the company's equestrian choreographer and she took inspiration from the great films of the day such as Doctor Zhivago, My Fair Lady, Robin Hood, and Gigi.

In 1965, her equestrian creation set to George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue set the foundation for modern presentations of free horses: the animals had no artifice, and worked in lighting enriched by the effects of smoke which reinforced the dreamlike dimension of the performance. Paulina Schumann introduced unusual and costly artistic and musical research into her performance, especially in terms of costume design. She blended light, music, and costumes around a theme and produced a veritable equestrian event. The Schumanns worked mainly in permanent circuses where they would remain for several months, thereby taking the time to rehearse their acts, which were then embellished with Paulina's ideas. Inspired by international folklore, she created magnificent scenes in which several dozen horses played the lead role. The Carnival of Venice, Madame Bovary, and Fiesta in Seville are some of her most significant creations. In France and Switzerland, The Grüss and the Knies continued this reflection on the equestrian art and created sumptuous scenes in which costumes, lighting and decorations all harmonised perfectly to combine all the magic of the original circus in one act.

Two hundred years after this western artistic form first appeared, Chinese linguists have recently combined the circle and the horse, creating a pictogram to illustrate the word circus, in reference to a western artistic form. This goes to show just how far the animal has permeated the imagination of the circus world, and given it such a symbolic dimension.