by Pascal Jacob

The designation of equestrian games is related both to identity and confrontation. A matrix for what would become the modern circus, these exercises were marked by references to a historical context and naïve theatricality. They were based on a very simple framework that went from brief skit to equestrian pantomime, narrative structures that were very efficient for dissociating them from pure exhibitionism.

The circus was symbolically born on horseback and the animal has constituted one of its major artifices since the second half of the 18th century. By developing a circular "play" ground for horses and riders of a diameter considered standard from 1779, the circus led to an obligatory repertoire of forms developed from one single support. The choice of the horse was no doubt linked to the current economic climate: it was a good time for buying animals abandoned by the army, and for offering demobilised military men a way to capitalize on their training and riding skills. Incorporating the horse into a show framework was not new, but what the pioneers of modern circus designed, would, of itself, distinguish a dynamic form that aimed to entertain.

The early equestrian games were based on the "simple" ability to stand upright on a galloping horse. As trivial as that may seem, therein lay the fermentation of a style of riding that was more tantalizing than academic, even if dressage and the haute école very soon helped to give the circus show credibility. Philip Astley was probably a better trainer than he was a rider, but he willingly made sacrifices to anchor the performance in a successful and skilful perception, by balancing on his horse to incite applause and donations. It was he as well, who wore the get-up of a military suit to create the first comic, equestrian skit in history. In 1768 in Brentford, he performed La Course du Tailleur, a clownish sequence inspired by a news story of the time, and that heralded the diverse propositions that arose from working with horses.

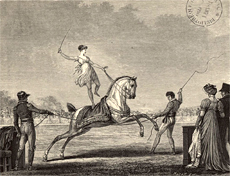

In the second half of the 18th century, riders and acrobats found a constant source of inspiration in frescoes, mosaics and antique statues, more approachable since the rediscovery of the Greco-Roman world, as well as the early, regular archaeological digs in Pompeii from 1765, the publication, in 1751 and 1772 of Diderot et D’Alembert's Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des metiers, Louis-Antoine Bougainville's expeditions, and, more generally, the development of an immense curiosity about the universe and its mysteries. La Renommée, (fame) embodied by Madame Franconi and illustrated by Carle Vernet in 1802 suggest artists' fascination for a historical period rich in forgotten references.

Le Chasseur Indien (the Indian hunter), made popular by Andrew Ducrow in the early 19th century, was taken up later by Paul (François Laribeau), and the Franconi's "beautiful rider," a skit embodied by a rider dressed in a light tunic, the chief decorated with multi-coloured feathers, was a good illustration of the diverse "outfits" that gave original character to a series of exercises shared by acrobats throughout the ages. The energy, spirit and allure of the rider was a big help in distinguishing the performance, reproduced elsewhere in other attires.

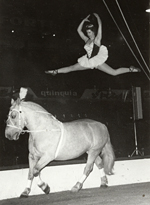

The momentum initiated by Astley in England and in France was decisive, and equestrian games became fashionable, mechanically generating a desire to increase the show offer. The Franconis, a family of Italian origin who constituted the first French circus dynasty, were at the origins of a certain number of creations and codifications of a genre that was already undergoing great transformations. Laurent Franconi, trained by Jules Pellier, encouraged the development of academic horse riding while his wife, Catherine Cousy-Franconi, embodied astonishing mythological figures on horseback, draped in a toga to perform La Renommée before the stalls packed with a delighted audience. She was also behind ribbon jumping, a discipline illustrated in 1890 by Georges Seurat in his last painting, The Circus. She opened the way for female riders, fragile silhouettes soon dressed in frothy skirts borrowed from the ballerina's wardrobe from 1831. By offering a sort of precipitate of the great romantic ballets on their horses, they also initiated a brand new taste for a light narrative form that would have its second wind with the 1849 creation of the panneau, a large wooden saddle covered in leather and which looked like a miniature stage. With the panneau, designed by American James Morton, another type of equestrian dramatic art took shape, The broad and relatively stable surface that this new support provided enabled the composition of veritable equestrian pas-de-deux, in an acrobatic extension of the choreographic repertoire.

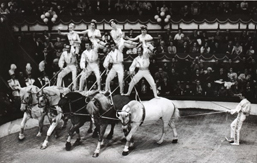

Several years earlier, the British rider Andrew Ducrow, nicknamed Proteus on horseback, created the Le Courrier de Saint-Pétersbourg, at the Amphithéâtre Astley, in an extraordinary performance seen for the first time in 1827. The feat was to stand up on two galloping horses, with one foot on each, keeping them sufficiently far apart to enable other horses to pass beneath this improvised bridge, while catching hold of a rein carefully wrapped around a horse's neck, and which, unwound, enabled five, seven, or even nine, eleven or fifteen horses to be harnessed. Each horse wore a small flag to symbolise the different territories crossed by the "post." the exercise created a spectacular effect and was transposed to different countries and regimes, giving The Royal, National or Imperial Post, but its influence over the audience and both male and female riders that took it up, was incommensurable with the rest of the repertoire. Laurent Franconi, Paul Laribeau, Paul Cuzent, Paul Lalanne and even Philippine Tourniaire in turn mastered the extraordinary performance, which was taken up regularly until the present day, by riders in search of strong sensations.

The first half of the 19th century was also a time in which military manoeuvres were reconstituted in the ring. Immortalised by the painter Victor Adam, they found an unusual echo in Le Quadrille des Lanciers du Bengale, an energetic and colourful equestrian scene performed on the Pinder circus ring in the 1950s.

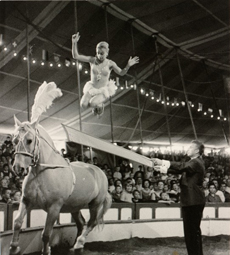

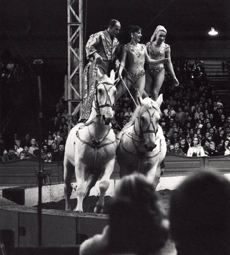

Gradually, performance innovations combined together to forge an ensemble of purely equestrian disciplines capable of constituting a complete programme in their own right. The fragile poetry of the panneau rider combined with sober artistic poses or living statues – an exercise based on the immobility of the horse and its rider carefully dressed or powdered in white – and like the blossoming raw strength used to master The Post, soon pyramids, elevations and juggling would offer new possibilities for the development of collective and individual forms.

Companies such as the Cristianis, the Loyal-Repenskys, the Sobolewskis, the Hannefords, the Carolis, the Richters and the Grüsses, made use of powerful family structures to construct the famous pyramids on three, four or five horses, creating impressive human houses of cards, solidly camped on the back of these animals with military allure, and guided by a master rider who carefully regulated their pace. With a base of four horses, a dozen people mounted the shoulders of the carriers and created a fantastic "living wall" effect.

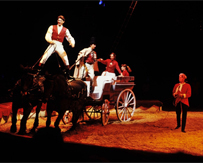

A variation on the same theme saw a platform harnessed to two or three horses on which the riders took their places. Alexis Grüss revisited this idea in the 1980s with Phaéton, an elegant car with pure lines that encouraged both a context for the act and solid bases for those incorporated into the rhythm of the horses. The Ali Bek Cossack company of Russian origin provided an astonishing version, with the addition of a pole planted in the centre of the platform, used for original balance postures supported by this perch of several metres high.

This blend of disciplines, the Chines poles in this instance, was common in the 19th century, with horseback juggling demonstrated early on by the skilful exercises of Pierre Mahyeu and Jean-Baptiste Auriol, the horseback foot juggler Roméo Capité, and more recently Servat Begbudi's and Stephan Grüss's performances following the tradition of these unusual assemblages in which the animal is definitively established as a powerful support for all variations.