by Pascal Jacob

A neck that draws a sinuous arc; hindquarters like a hill; a thick, flowing mane that is part veil and part waterfall; and precise, perfect legs anchored to the ground by powerful, round, immense hooves… When Caravaggio painted The Conversion of Saint Paul on the Way to Damascus, he lost himself for days on end in contemplation of a creature so alive that it ended up filling his canvas.

"His" gigantic horse conquers the canvas, almost engulfing the subject, and becomes the radiant centre of the work. Obviously, it is not a circus horse, but this fantastic animal's coat irresistibly evokes the piebald horses of the Irish Tinkers, a fascinating gypsy community that have inhabited the roads of the Emerald Isle for centuries. These heirs to, and members of a universal diaspora, have always worked with horses. Since the dawn of humanity, mythical, legendary creatures such as Pegasus, Bayard, Bucephalus, as well as centaurs, unicorns, and amazons, these powerful and evocative creatures, have woven a web of troubling complicity between the horse and the peoples who have tamed it, or who keep it to magical ends, representing it on a multitude of supports, whether improvised, or carefully prepared.

Sources

Small horses gallop across cave walls at Altamira and Lescaux. With neither rider nor plumes, they nevertheless embody this very human intuition of taming and training, and the proclivity to understand and retain a primitive impetus destined to be transformed into a companion for centuries to come. In painted form, wild horses are already "tamed." Of all the creatures idealized by man, they were the only ones to achieve the status of partner, in a prelude to an extraordinary development for future horsemen and women.

A 1772 engraving shows Japanese warriors, carried away by the spirit of the mounts, accomplishing balance postures and swinging under their necks. This is an obvious similarity to the Mongolian horsemen who inhabit the plains of the Middle Kingdom, and whose traditional instrument, the morin kuur, has volutes decorated with a small horse's head, representing an unfailing attachment to a living creature that is an integral part of the future of a community linked to its power and docility. When George Stubbs painted the horses of the British aristocracy, James Pradier sculpted the circus rider Antoinette Lejars on her horse Thisbee, to decorate the façade of the Cirque des Champs-Élysées, in exchange for permanent free access to the performances. And Monsieur Wulff, the circus director, had Belgian artist, Godefroid de Vreese, make a sculpture of him on horseback, looking upright and dignified. This bronze piece is a noble, and durable, elegant effigy. It is no coincidence either, that John Bill Ricketts, founder of the American circus, had himself portrayed with a horse's head in the background, in a painting that is now kept in the National Gallery in Washington, and which supports the importance of the horse from the beginnings of the equestrian show form.

Transpositions

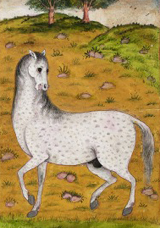

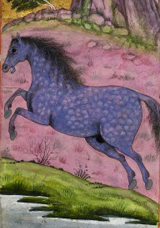

Art mirrors man's fascination for horses, as seen in numerous pictures, paintings and miniatures, from Moghul India to the Chinese Empire, and from the fascinated West to America, stunned by this high-spirited partner of every conquest. In addition, the animal adored by princes and paupers alike, also decorates the chessboard, one of the most ancient games in the history of humanity, as well as several more recent board games. Sculpted in prestigious workshops, the horse decorates innumerable merry-go-rounds and gallops humorously along the paths of popular culture in images in which the spirit, hoof, and mane take the lead role.

A companion in travel, work, and war, the horse spans all of mythology, from one end of the world to the other, from the borders of the East, to the far-flung boundaries of the West. Epona is a major goddess in Celtic and Gallic cultures, and her cult can be seen in multiple Gallo-Roman sources. She is associated with the horse, the emblematic animal of the Gallic aristocracy, whose campaigns helped spread her cult. Rhiannon is the equivalent Celtic goddess in Wales, and in Ireland she is known as Macha. Her rider's cult was broadly accepted by Roman civilization, which adored waters and horses. Represented by a mare and a horn of plenty – sometimes replaced by a bowl of fruit – she is the major horsewoman goddess, or mare goddess. What Epona emphasizes is fascination, mixed with respect and adoration, for an animal so close to man that its existence merges with that of its riders.

Reflections

The "centaurisation" of the circus rider, in effect since François Baucher and Ernest Molier, largely helped recognise and appreciate a unique equestrian model, at the symbolic crossroads or academic riding and exhibition riding. Since 1989, the well-named Théâtre du Centaure, has honoured this complicity rider and mount, in compositions of a new style, where it is hard to tell whether the horse is talking or the man is kicking…

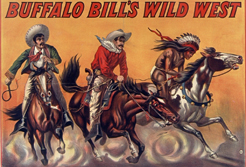

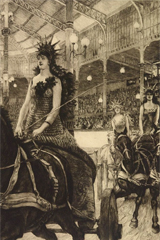

In the 19th century, through its closeness and attachment to a set of initiates who frequently attended performances, the circus helped anchor the shape of the horse in the daily existence of painters and sculptors. Frémiet, Pradier, Géricault, Vernet, Adam, Tissot, and in particular Toulouse-Lautrec, drew inspiration from the ring and behind the scenes for spectacular new motifs, amused illustrations and impressive canvases, in which the circus dimension of the acrobat was either literal and dazzling, or more discreet. The talented Rosa Bonheur painted a faithful rendition of the famous William Frederick Cody when he toured France in 1905, giving the man more commonly known as Buffalo Bill, an elegant, refined painting which served as the framework for a circus poster.

By giving centre-stage to a winged horse, Picasso tied the ghost of Pegasus to his imaginary universe and conveyed his fascination with this extraordinary creature on the immense curtain canvas of a scene for the ballet Parade, create din 1917 in Paris by the dancers of the Serge Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. In this stage curtain, inhabited by the emblematic figures of the ring, the painter's work flamboyantly sealed the pact between the circus, and 20th century art. Joan Miró in turn interpreted and questioned the circus horse in a dozen canvasses painted between 1925 and 1927, while Marc Chagall, executed a series of 19 gouaches based on drawings created in Ambroise Vollard's private box at the Cirque d’Hiver.

Raoul and Jean Dufy, Fernand Léger, Max Beckmann, Kees Van Dongen, and Marie Laurencin were also fascinated by the circus ring, and included horses and riders in their visual repertoire, tracing a different, symbolic, and powerful perception of the circus. As such, they helped anchor a popular artistic form in another realm of the collective imagination. Aesthetic and vibrant, "their" circus resonated on museum walls, and galleries, and decorated the salons of collectors fascinated by this metaphoric interrogation of a Bohemia that resembled them in its independent spirit and disdain for conventions.

Footbridges

From the Roman de l'écuyère by Baroness Jenny de Rahden, to the La Dame du cirque by Guy des Cars, the literary position was one of amused distance regarding the rapport between a horsewoman and her mount, who were the emblematic figures of a colourful and dynamic universe, and a pretext for writing spectacular or romantic scenes. It is also difficult not to see an amused allegory of the clown and the buffoon in the conflicting and complicit rapport woven between Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, both horsemen, and both defeated by the twists and turns of a rigid, distant society, little inclined to tolerate fantasy and extravagance.

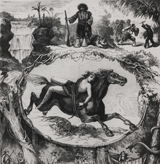

Lord Byron's Mazeppa, a dark tale of infidelity and revenge set in the Ukrainian planes in the Middle Ages, served as a powerful and spectacular framework for an evocative pantomime. This could be short or long, depending on how inspired its creators were, and was transposed into the circus ring, essentially for an instant of bravura when the punished Ukrainian officer – the now famous Mazeppa – is tied, naked, to his horse, and given up to the hungry wolves that inhabit the Steppes. This strong and vivid literary episode spawned several film works, including Bartabas' Mazeppa, which is a magnificent fresco inhabited by the circus rider Franconi, and the painter Géricault, portrayed by the actor Miguel Bosé, tied naked to a horse chained to a conveyor belt, in the magnificent final scene of a sumptuous film, in which man and horse are forever bound. From a conversion to a condemnation, the links that unite man and horse are therefore symbolic of an almost sensual relation, in which complicity and precision are both the driving force, and the raison d'être, in a story of domestication and civilization.