by Pascal Jacob

A wire. A dash. A line. Of strength and of life: stretching a tightrope from one point to another is a militant act. It is a way of connecting two points, of bringing them closer together, of abolishing a distance and of sealing a destiny. Extending a tightrope, stretching it to its most extreme point of tension, forcing it to bear a moving weight, a body in action, is also to symbolically mark a conquered territory over the void. By the grace of crossed pieces of wood or metal, held by a vine, a rope or a cable, placed anywhere, in a public square, on a stage or in a circus ring; a new play area is created from scratch, both light and routed to the ground. Stretching out one's tightrope, for oneself and for others, creates habits and obligations. A duty of memory and action. But extending a tightrope to dance upon is also to take risks...

Few disciplines carry within them so much supressed ambivalence; imperceptible to the uninitiated who often retain nothing but an artificial lightness. Walking on a wire is an act of faith. A proof of abnegation and courage. Taut, hard and sharp-edged, the tightrope remains the familiar companion of those who tame it daily. A demanding discipline, the tightrope is its own language. It is articulated through a vocabulary, resting upon technical mastery and leaving very little room for indecision.

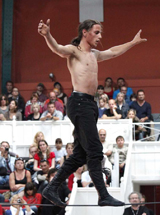

But it is also a fantastic pretext for drama. Symbolic, effusive, spectacular, the tightrope passed through many stages before beginning to question its evolution; the evolution of its technique as much as that of its meaning. It is a question of composing with the void: on his tightrope, the acrobat is always at the centre of something. His body is an axis, his mobility a means of building a sequence. A simple stretched wire, with no other trick, is a first step towards the mystery of balance, or mastered imbalance; a living incarnation of the figure of the acrobat as a factor of progress.

Filiation

Nowadays, we still practice the art of balancing on ropes, but also on taut, loose or slanting wires. Depending on which of these three types of wire they work upon, artists perform jumps and manipulate objects, using their hands, a fan or a parasol, at times integrating humour and developing a festive, offbeat and poetic approach to an apparatus which is both simple and complex.

The tightrope and high-wire walkers who trained in the specialist circus schools take, for the most part, a creative approach, but they are also part of a historical lineage and are intuitively in harmony with earlier innovations, like that of the Voljanskys and their creation Prometheus in the 1950s, a circus piece for high-wire walkers that occupied the entire second half of a show and heralded the notion of small, monodisciplinary formats. The Soviet troop, the Voljanskys, are pioneers: exceptional high-wire walkers, they rely on words to join and justify each of their actions, progressively building and taking on the discipline’s inherent share of tragedy. Prometheus, a collaborative creation, was a strong artistic gesture at a time when the high wire was primarily just an act. Their work attests above all else to the potential of a technique that is capable of lending itself to a subject matter, not just illustrating it but embodying it. The creation of La Volière Dromesko, in the early 1990s, aimed to achieve a similar level: the myth of Icarus, represented by 250 birds flying freely under the translucent dome of a big top erected around a tree, was also led by high-wire walkers, Agathe Olivier and Antoine Rigot, future founders of the company Les Colporteurs. After followed their creations Amore Captus and Filao.

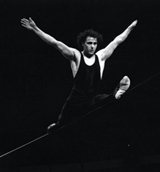

"I have no reason to be afraid of falling. I cannot fall. Up there, unsuspected reserves of energy come to me. It is like a mother seeing a truck rolling over her child, so she slides underneath to save it. If you are on the edge of a volcano with a broken leg and it erupts, you are going to run, that's for sure... On a cable, I feel indestructible. Otherwise, I would not go."

Philippe Petit, Traité du funambulisme, 1999.

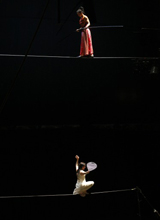

Le Fil sous la neige showed that the wire could, like juggling, trapeze or acrobatics, be the central element of a show. Eight wires were stretched to different heights, overlaying and crossing each other, for seven high-wire walkers who never set foot on the ground... The company Le Boustrophédon, integrates the high wire into its dramatic creative approach and creates strange little characters, some of whom, inspired by the Japanese bunraku technique, wander about on the cable with magical grace. Between puppetry and the phenomenon of "mimed ventriloquism," the fragile silhouette of Pétule opens another perception of the high wire; both touching and powerfully theatrical, the eye forgets the puppeteer, retaining only a moment of raw poetry embodied by a tiny figure, an immortal rope dancer gifted with a life of her own. With the creation of the show Camelia, the company developed a prodigious balancing-on-crystal-glasses work, dematerialising the wire and thereby giving it a better symbolic meaning: Camélia is also a character, a little ballerina from the distant past but who retains a devilish virtuosity...

New directions

Despite its installation constraints and its tension requirements, the high wire is a very popular discipline in specialist circus arts schools: this new accessibility contributes greatly to the dissemination of the high wire, but above all it supports aesthetic evolutions on the high-wire and is leading the practice in multiple directions. In Danse au fil du vent, a show created with Micheline Lelièvre, Johanna Gallard highlights the power of a rhythmic approach to high wire work. Her collaboration with choreographer Thierry Guedj anchors some of her evolutions to the ground, sharing physical balance and the imbalance of improvisation and using them to express the fragility of a discipline with multiple constraints. The high-wire artist Marion Collé who trained at the Académie Fratellini and the National Center for Circus Arts Châlons-en-Champagne, chose restriction and constraint to form another approach. Progressing and weighted down with a stone attached to her waist, her walk along the wire puts Sisyphus back at the centre of the process of constructing an acrobatic, choreographic and "wire-ic” piece. It is a beautiful paradox: where many prefer lightness, sliding and rapidity, she anchors herself to the ground and plays with slowness.

For her, the wire and writing are forms and structures that nourish creation. Writing enriches the wire, from the head to the body, and the wire feeds writing from the body to the head. A meaningful duality in a singular approach where the intimate rubs shoulders with the exuberant, where a line of writing is symbolically superimposed on the very real line of the steel cable. Blue, the first piece by MarionKa, the young wire-walker’s company, is also a powerful and vibrant manifesto discussing which anchor points of memory and meaning a contemporary "wire-ish" form can be tied to.

Tatiana Mosio Bongonga, one of the few tightrope walkers trained at the National Centre of Circus Arts at Châlons-en-Champagne, introduced a new perspective in her work by juxtaposing an exceptional level of performance and an apparent deconstruction of style. Alexander Weibel Weibel, who trained in Stockholm, invented a new structure: six wires instead of one, which split and overlap one another, enveloping and binding him, but above all enabling him to attest to and prove that creativity is inexhaustible.