by Pascal Jacob

When Philippe Petit (1949-) speaks about his work, he talks about the wire, the steel cable that followed the hemp rope, its installation between two poles, the buffalo-skin slipper used for walking in the sky, the wooden or metal balancing pole that boosts crossings at great heights, the focal point, the wind, the solitude, the fear. In 1971, by discretely extending his wire between the towers of Notre-Dame, the wire-walker ensured a symbolic connection with the former illustrious acrobats who have enchanted Paris since the Middle Ages. An entirely clandestine poetic outburst, his crossing at once frightened and delighted the Parisians who caught a glimpse of him from the square below. At the same moment, a ceremony of vows was taking place in the cathedral: future priests were lying on the ground with their arms in a cross, unaware of the "drama" that was playing out above them, creating a striking contrast in this unexpected juxtaposition of events, as different the one from the other as it is possible to be, except that for Philippe Petit, there is something of a sacred order in this appropriation of the sky... Although it is not common, the desire for touching the clouds is not a new concept in Paris. For the arrival of Isabeau of Bavaria in 1385, a wire-walker slid along a rope stretching between the tallest tower of Notre-Dame and the Pont-au-Change, singing all the while he leapt over a wall-hanging scattered with fleurs de lys, placed a crown upon the new queen’s head and set off again in the direction for which he came, two bright torches in his hands, which from the point of view of those watching from afar made him seem like an angel descending from heaven to greet the sovereign...

Philippe Petit would reiterate his feat by stretching his wire between the towers of the Chaillot Palace, this time with valid authorisation, for a Jacques Higelin concert in 1984. He would go even further a few years later, in 1989, by attaching his wire to the second floor of the Eiffel Tower for a long ascent of several hundred meters between the sky and gardens.

"Camilla Meyer was a German. When I saw her, she was maybe forty? She had erected her wire thirty meters above the paved streets of the Old Port in Marseilles. It was night-time. Spotlights illuminated the 30-meter-high horizontal wire. To reach it, she walked up a two-hundred-metre-long slanting wire which started at ground level. Once she arrived at the halfway point of this slope, to rest she put a knee on the wire, and kept her balancing-pole resting on her thigh. Her son (he was perhaps sixteen years old) who was waiting for her on a small platform, brought a chair to the middle of the wire and Camilla Meyer, who started from the other end, arrived at the horizontal wire. She took this chair, which rested on only two legs on the wire, and she sat down on it. Alone. She got off the chair, alone… Down below, under her, all heads were lowered, hands hiding their eyes. By acting in this way the public refused the acrobat a basic courtesy: making the effort to watch her as she brushed with death"

Jean Genet, Le Funambule, 1958

Legends and Reality

For a long time, the wire-walkers were suspected of chewing the same roots that the chamois eat in an attempt to acquire the same agility on the steepest of cliffs. Creatures insensitive to vertigo, the wire-walkers are undoubtedly the true ancestors of aerial acrobats. The cord can be rigged anywhere: tied to a tree, a column or at the top of a house, and it offers a fearless acrobat a way of proving his bravery. The Uyghur wire-walkers, who plant their poles and tighten their ropes in fields at the entrances of the mountain villages that they have been visiting for several centuries, practice the same dance that Western wire-walkers perform, like the Knie’s who travel with an open-air arena, but who also stretch their line over rivers or attach it to towers or belfries for exceptional performances.

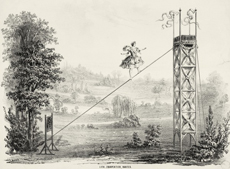

Dancing on the high wire, or wire-walking, has long been one of the most popular forms of acrobatics. No doubt because it delivers man to infinity, suspending him between heaven and earth. Marked by a tendency to outdo itself, the discipline was first practiced in the sky, that is to say almost without limits, throwing a line over the abyss and thus connecting the most unlikely yet most spectacular spaces, by the virtue of a trail marked out against clouds. The practice of the wire-walker is largely solitary. The first of their kind, in Ancient Greece and Rome, progressed on the high-wire and concentrated on the unique nature of their performance. With the taste for risk that permeated the circus at the end of the nineteenth century, wire-walking started being practiced in troops: the start of the following century saw the advent of dynasties, from the Triskas and Omankovskys to the Wallendas, families-cum-troupes who have multiplied their technical prowess and invented unbelievable constructions tens of meters from the ground. The famous pyramid of seven, somewhere between a card tower and the ship of fools, is engraved in the Wallendas’ repertoire to this day, and was used and reworked by the Guerreros under the domes of the giant American arenas.

Ever higher

Distance incites a decorative one-upmanship: Blondin, a French wire-walker who volunteered himself for a Niagara Falls crossing, was dressed in a pink silk leotard emphasised by a red glittery jersey, his head decorated with a gleaming helmet crowned with a plume of multicoloured feathers. This "plumed helmet ", worn by Antonio Franconi, Madame Saqui and most of the wire-walkers in the first half of the nineteenth century seems to be an emblematic prop of the trade. This strange outfit made them visible from afar and reinforced the spectacular dimension of their work. Blondin also used a long balancing stick, lead-weighted at the ends, giving it a deep curve, like a disproportionate bow whose ends were lower than the cable: the wire-walker’s balance is reinforced by this device without diminishing, for all that, the risk of the crossing.

Blondin’s work is part of a long lineage dating back to Antiquity and is continued today by certain wire-walkers who still dream of conquest: on the 15th of June 2012, Nik Wallenda crossed the 600 meters above the bubbling waters of Niagara Falls in 25 minutes. Didier Pasquette, Jade Kindar-Martin, Jean Thierry Barret, Michel Menin, Pedro Carillo, Manfred Doval, Gene Mendez, Sacha Cortès and David Dimitri are the heirs of the Greek oreibates, conveyors of emotion throughout the centuries.

With the wire-walker, the world has once again taken up its former fascination for somewhat crazy exploits, both unbelievable and magnificent, symbols of the energy of a Humanity where fragility and power have always been combined. By hanging their cables from belfries or hills, the acrobats of yesterday and today are part of the invisible fabric of society; honest, sensitive silhouettes, ephemeral members of a community with innumerable accents and motors of an interest that remains intact.

Interviews