by Pascal Jacob

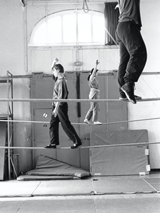

The wire belongs to the balance disciplines. The term "wire" comes from a word of Latin origin stemming from notions of equality and balance, a logic of oppositions that end up cancelling each other out to define a neutral point of immobility and perfect balance. Obviously the tightrope technique has little to do with immobility, preferring instead a repertory of rapid jumps and movements, more will-o'-the-wisp in style than statue, but balancing the body is the decisive element in developing these poses and figures.

"(…) Some animal tamers resort to violence. You can try and subjugate your rope. But beware, the tightrope, like the panther and the people, they say, has a thirst for blood. Why not tame it instead?"

Jean Genet, The Tightrope Walker, 1983

It seems very difficult to define a logic of precedence, progression or differentiation between styles, techniques and disciplines when trying to describe practitioners of rope dancing, high wire walking and tightrope walking.

Semantics leans towards Greek roots, but the common use of the term funambulus in preference to schoenobatus, pleads for a Latinization and as well, for a context of development situated in the South of Europe, although in the 18th century, with a helping hand from fashions of the day, all rope dancers, regardless of their real nationalities, were Turkish! What is sure however, is the permanent aspect of the apparatus, composed of two wooden "crossed posts" that held the rope at the desired height. An ultra-simple device for acrobats admired by an audience that saw them as talented beings with supernatural powers. The two posts were different heights: the "back" one was higher, and decorated with a piece of fabric that acted as a seat or backrest during rest times. The other, "front" one, was lower, and constituted the "foresight" or focal point, that the ropedancer keeps his eyes fixed on when on the rope. In Europe, for a long time, the wood used to craft the posts was oak, which is both strong and flexible.

Practice and transformation

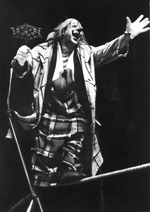

Whether a rope dancer, a tightrope walker or an orichalcien, a French term for one who walks on a wire, the acrobat can work on one of several wires, parallel or perpendicular, on a tight or slack rope, or on a hard or soft steel wire. They can play with horizontal or diagonal axes, and blend techniques, while combining distance, height, plans and directions. The Scotsman Duncan MacDonald enriched his practice by building up cumbersome obstacles. He would walk on a rope perched on stilts, playing a sort of trumpet, while carrying a cartwheel on his foot, and balancing a sword on the tip of dagger held between his teeth, while brandishing in his free hand a complex heap of objects and utensils including a chair.

Owing to the fact that rope dancers were banned from the quays and a good number of other places, they gradually organised themselves and created companies. The wire was a stage of its own, grounds for more or less nimble skits and jokes. It was by making the Duchesse du Barry laugh with a "saucy trick" on the rope that Jean-Baptiste Nicolet was awarded the title of Grand Danseur du Roi (the King's Grand Dancer).

At the end of the 18th century, rope dancing, which had become a dance on a simple brass wire before transforming into the "high wire act," was an important element on the menu of pleasures attached to stage shows. It was theatrical, providing those who practised it with multiple grounds for developing a sequence of skits with postures, costumes and accessories. Pure skill combined with dressing up for the performance, as practised by Madame Saqui, who played every role in the Moine du mont Saint-Bernard, an elegiacal pantomime that narrated the adventures of a traveller lost in an avalanche and saved by the monks and their dogs. Her rival, Hébé Caristi, dressed in a breastplate of scales, also performed every character in her stories, from the Marquis of Lassan to Marshall Lannes, from lost women to the terrified bourgeoisie, from captains to simple soldiers, but also, when the situation arose, Terror, Fury or Charge, representing spirits and figures, without words, but with fierce conviction. On 24 June 1809, in Tivoli, Madame Saqui inaugurated a rope dance without using a pole, and crossed the Seine a few weeks later, using two small flags as balancing poles.

Technical developments

Although rope dancing was created in the street, based on a very simple device in which it is easy to see a variant of the slack rope (a source of inspiration for the cloud swing, an ancestor of the trapeze), the principle of apparatus juxtaposition should also be admitted, nourishing and influencing each other, and above all, developed by human intelligence, which is always hungry for something new.

Acrobatic practices did not escape this rule and the development of disciplines, from creation to transformation, is often associated with a phenomenon of adaptation or recuperation, i.e., the possibility of using a crafted brass cable, know in French as fil d'archal, which conditioned the development of the technique in the 19th century. This wire could be tightened further, obviously gaining in spring capacity, and encouraging a dynamic transformation of the discipline. Inevitably, ropedancers adapted their movements and figures to this new medium. The wire is at the origins of an aesthetic upheaval, as it modified both the perception of the work and its energy to such an extent. Previously the act had been a sequence of movements complicated by chains or baskets on feet, balance postures on planks set across the middle of the rope, or ribbon or flag jumps. Now, the wire was used for jumps, either simple or more dangerous, leading up to the Holy Grail of the discipline, the now key, yet extremely rare, forward somersault, mastered for the first time by Australian Con Colleano in 1919.

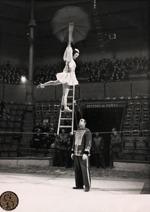

Up until then, the wire, which was theatrical and combined with jumps, had been considered a fairground discipline. From the 19th century, it was considered an art in its own right, and each discipline became independent: tight wire, slack wire, elastic rope and funambulism were established as the various ingredients in a classic show, but were rarely juxtaposed during the same performance. One or other of the techniques sufficed to tick the "wire" box in a programme. The tightrope is probably the most common speciality act, if only because it enables the image of the ballerina to be revived, and to add an additional female character, who is both strong and remarkable, to the development of the show. In the 20th century, the female tightrope walker was a substitute for the circus rider. Resembling her in both physically and in terms of agility, she added a touch of modernity, linked to the technical dimension of the apparatus. For indeed, steel evokes the industrial, and this pure, sharp cable has a perfectly contemporary ring to it. Moreover, there is a troubling analogy between the two disciplines, as the best circus riders, from Antonio Franconi to Oceana Renz, were also excellent ropedancers.

The discipline spawned vocations and created stars: in 1919, Bird Millman performed in the central ring of the American Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus, where, as a incredible privilege, the side rings remained empty during her act, which she performed while singing. Her speed and fluidity combined with the communicative joy of being on the wire were much prized in her act. The men were not to be outdone, and the intriguing Barbette, a transvestite trapeze and tightrope artist, enjoyed immense success throughout the world. Drawn by Charles Gesmar, photographed by Man Ray and described by Jean Cocteau, he embodied the eternal fascination of the audience for this spectacular, aerial technique.

Variants

In the 1970s, Philippe Petit stretch his wire between two trees on the boulevard Saint-Germain in Paris, between the Café de Flore and the Deux Magots. There he practised his rope dancing technique with humour and simplicity, before launching his attack on the towers of Notre Dame cathedral and winning praise for his art.

Today, the wire is almost a symbol of equality: girls and boys soar on the cable, developing their own technique and style, whether trained within a family or at a school. Agathe Olivier, and Antoine Rigot, Johanna Gallard, Maud Gruss, Molly Saudek, Nathalie Good, Marion Collé, Andy Monti, Julien Posada, Florent Blondeau, Kilian Caso, and Lucas Bergandi, among many others, have established a natural filiation with Gipsy Gruss, Mimi Paolo, Joseph Bouglione and Manolo dos Santos, aka Manolo.

Interviews