by Pascal Jacob

We are all tightrope walkers. Whenever we step onto a bridge, whether narrow or wide, short or long, the idea of crossing a void evokes our origins, and a time where simple need gradually transformed into a game of agility.

A liana, hanging above a ditch that was too wide and too deep to be crossed in one jump, served both as the fist bridge and the first wire. A lifeline sometimes, for hunter-gatherer societies who inhabited primitive forests and used their flexibility to go further in their quest for food, or to remove themselves from thorny situations.

When Zarathustra arrived at the nearest of towns (...) he found in that very place many people assembled in the market square: for it had been announced that a tight-rope walker would be appearing. And Zarathustra addressed the people with these words: "I teach you the Superman. Man is something that should be overcome. What have you done to overcome him? (…) Man is a rope, fastened between animal and Superman – a rope over an abyss"

Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, 1883, trans. RJ Hollingdale, Penguin UK, 1974.

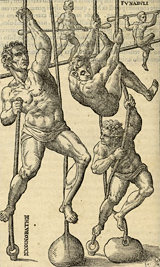

Etymologically, the Latin formulation does not take height into account. Between funis, "rope" and ambulare, "walk," the first intention is clear: it is the idea of progression that is referred to rather that a random evaluation of distance. In Greek however, schoenobates, oreibates and neurobates – those who used a cord – neuron – as a support for movements – and all gymnasts in ancient times defied the laws of balance: they ran along a high wire above the public squares, or stretched their diagonal rope – katadromos – (or "descent"), from the highest crossbar of the theatre to the orchestra. The roles were clearly defined, and although the former were capable of dizzying ascents and descents on the oblique rope, the neurobates defined themselves more as jumpers or balance artists. Sometimes complicating their movements by wearing buskins, they advanced on a very thin cord of hardened catgut, which reinforced the magical impression of a dancer suspended, as though walking above the void.

Recognising danger

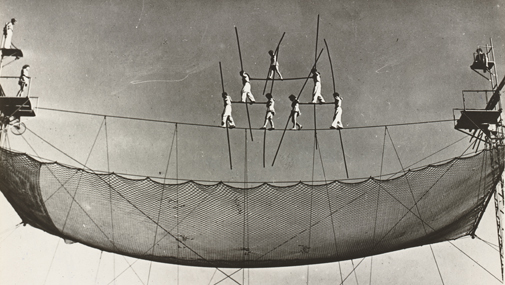

This technique is similar to the modern tightrope, both in the diameter of the apparatus and in particular, in its hardness and probable tension. From each of these specificities, a unique repertory develops, based on an exploit, and which constitutes a permanent game with death. The emperor Marcus Aurelius in fact, having witnessed the fatal fall of a young acrobat, imposed the use of a protective mattress in a humane gesture that endured after his reign, only to disappear during the modern period. Still today, most tightrope walkers in the West work without a safety line, net or mattress, in a blend of pride, absolute certitude and lack of awareness. But that is the price to pay for the gripping fascination experienced, both on the wire, and in the audience.

The native inhabitants of Cyzicus, an island in Asia Minor, were, in the eyes of the chroniclers of the day, the best rope dancers in the world as they knew it, capable of accomplishing a wide variety of feats, including somersaults, which they supposedly invented… In the 13th century, a company of Egyptian tightrope walkers, one of whom carried a child on the shoulders and jumped from one rope to another, performed throughout Europe successfully: the initial 40 members of the company seem to have been reduced to about 20, a carnage justified by the mad daring of the acrobats.

Laws and obligations

From the start of the 17th century, rope dancing was subject to laws on the privileges accorded to certain theatres. The acrobats were not allowed to utter a single word, nor even sing, and tolerance for their "dance" was only justified owing to the specific nature of their exercises. In 1619, the tightrope walker Claude Aduet performed at the Saint-Germain fairground and had to pay a fine for having worked without authorization. In 1681, the Tous les Plaisirs Company suffered the same misadventure with Sieur Languicher, the only "rope dancer to the Kings of France and England," additional proof that these privileges led to a hard life. They were abolished definitively only with the fall of the Second Empire.

Still in the 17th century, one man danced on a high wire perched on stilts, while another attached daggers to his knees and walked at a great height, multiplying the grounds for wonder and admiration. At the very beginning of the 19th century, in Dresden, the famous Forioso suggested to city councillors several times that he could cross the Elba… At the end of the same century, Emile Gravelet, aka Blondin, would cross the Niagara Falls.

Tightrope walkers and rope dancers were also heirs to a long far eastern tradition. A fresco from the Han Dynasty period found in a tomb in the city of Yinan (Shandong province) shows three young girls jumping, dancing and standing on their hands on a wire suspended above four daggers fixed in the ground, pointing upwards. In his Chronicles of the western capital, the well-read scholar Zhang Heng (78-139) described, vividly and precisely, certain acts practised by acrobats of the time, masters of rope balancing. What he did not specify however, was whether it was a slack rope or a tight one.

Dance and the tightrope

The act of walking on a rope, a brass, wire or a steel cable was long considered an aerial discipline. Moreover the slack wire has obvious similarities to the cloud swing, itself an ancestor of the trapeze. However, when the wire is taut, it becomes an autonomous and dramatic discipline apart. Tension makes the wire hard – which is another way of describing it and stigmatising the technique. When the acrobat leaves the platform and glides out onto the bone sharp cable stretched between two points, he is facing the void. It is a metaphorical desire to master an ancient form of imbalance, and an elegant way of knotting the strings of the profane and the sacred. The wire is an elegant metaphor for an acrobatic art that has lasted throughout the centuries. From the Roman arenas to contemporary big tops, it is probably the discipline that best illustrates the permanence of acrobatic forms in the West.

Heir to rope dancing, "tightrope walking" appeared in the 19th century and was established as a formidable device for developing astonishing feats in which the elasticity of the apparatus is decisive. As a propulsion technique, it is based above all, on a repertory of jumps, of which the somersault is perhaps the most rarely mastered, even today. Only a handful of tightrope walkers, perhaps ten in all, is capable of performing it regularly around the world.

The tightrope walker demonstrates magical agility when moving on the wire, as he glides confidently onto a cable stretching from one side of the ring to the other. Is it a dancer balancing or a balance artist dancing? For early 19th century admirers, the rope dancer Ravel, was "Vestris (…) on a theatre half the width of a foot."

According to accounts from the era, "elegance, flexibility and neatness" characterised his movements, while his ease and confidence erased all appearance of difficulty. But above all, he was admired, unreservedly, and with a serene heart and mind, where one trembled before his competitors. He soothed the spectator with his skill and perfection, and really showed himself to be "the incomparable one." In the following century, one of the greatest tightrope walkers of all time, the Australian of Aboriginal origins, Con Colleano, who looked supremely elegant dressed as a toreador, was also nicknamed the "Vestris of the wire" a blatant reference to the legendary excellence of the 18th century rope dancer.

Dance and wire are closely linked: aplomb, posture and balance lie at the very heart of the two practices. Placement, breathing, control, concentration and rhythm and holding… everything is based on the foothold, a mobile pelvis and a deep perception of rhythm, control of the breath and the perception of the cable.

Dance and wire share a similar vocabulary and phrasing, but at the instant when the foot touches the wire, ready to carry the body along, the references tend to cancel each other out. The fragility of the approach, and the paradoxical blend of hardness and elasticity is disconcerting. The wire is a strange support that both rejects and welcomes simultaneously.

Ascent

Dance, in the generic sense of the term, is part of the genetic code of the wire: the terminology applied to ballet naturally harmonizes with that of the cable, rope and wire practitioners. Figures, postures, steps and attitudes help structure the discipline and forge the allure of its devotees. It is just as demanding as ballet and a good number of fragments from the repertory were shared during the 18th and 19th centuries. The same steps are found on the wire as on the stage. Moreover, the term "rope dancer" is unequivocal: it describes, deliberately, a blend of genres between a classical ballerina and the as yet unlabelled tightrope walker.

The boundaries of the genres are even blurrier if one accepts the idea that point shoes stemmed from the fairground, as the prerogative of acrobats transposed onto prestigious court stages in the first half of the 19th century. Paradoxically, the fragility of the ballerina, anchored to the ground only by the point of her shoe, has something of the funambulist: coated with rosin, the shoe adheres to the stage, and rosin also prevents the acrobat from sliding too quickly.

Heirs to ancient oreibates and rope dancers from the Middle Ages, the 19th century tightrope walkers used a hard, sharp, steel wire to develop a repertory of classic figures imagined and coded from the very first steps of the discipline. The difference between the work of the tightrope walker and the funambulist is essentially a question of height. The former rarely works more than two metres above the ground, while the latter has no limits. The French funambulist Philippe Petit always favoured extraordinary exploits, and stretched his wire between the two towers of the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, across the Niagara Falls, and between the Twin Towers of New York's former World Trade Center.

The first funambulists attached their wires to church bells or cathedral towers: the sky was the limit, and the city, at their feet, created an ever-changing landscape. The circus would modify the perception of their work by reducing their playground to the space of the big top alone, and the rope dance – the grounds for and an arsenal of feats – became a circus art, once and for all.