by Marika Maymard

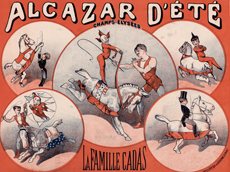

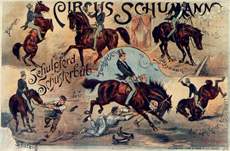

In the equestrian circus track, you will find acrobats in uniform, proud Amazons, dressed riders and horsewomen with panels accompanied by eager clowns. But to renew a rather classic program, lighter sketches are developed to surprise or make people laugh. Clowns give life to cloth horses and make them gallop and, on the other hand, horses take on the jobs of skilled, balancing animals, calculators or comedians.

The training of the horse actor requires the exploration of registers that are quite far from its natural behaviour, respected in academic equitation. For his "acting" to be credible, the animal must engage in learned postures and provide the reply without making mistakes. Even praised by its trainer for its "intelligence", the horse cannot claim the agility of a monkey or even a dog. The repertoire of sequences that can be performed is therefore smaller. When choosing a horse to help him accomplish his project, the trainer will observe and give a real audition to his four-legged "actors". The selected horse can then begin its instruction. If it succeeds, its name will appear in the cast of the play, such as Zisco, instructed by Mr. Huillier, for Le Cheval du Diable, presented at the Théâtre du Cirque Olympique in 1846.

A hierarchy of performers

The trained donkey is a formidable accomplice, even in the ring of large establishments such as the Nouveau Cirque de la Belle Époque. As a partner of the clown, it quickly assimilates certain gags such as picking a spectator's hat from their lap, or a cabbage or carrot, and then going off in a caper to avoid whipping, while little dogs and pigs wearing collars or star cones run between his hooves.

Intuitive, the pony can adapt to sudden changes in pace or rhythm, to kicks or turns on itself that will make the rider's efforts to maintain a dignified attitude or simply to stay in the saddle quite funny!

The mule offers a flexibility and confidence that comic trainers like John Ducrow or, closer to home, Pieric, use to create unexpected sequences from somewhat placid looking animals.

Cast against type

In the wild, the horse spontaneously chirps in front of the mare, hooves raised. Similarly, it takes a fighting posture, anterior forward, against another male horse in the quest for group domination. Seen to take on the role of boxer, a fashionable profession at the beginning of the 20th century, the horse must reproduce these movements, not by instinct but by learning, since it is not a question of achieving the natural outcome in terms of mating or fighting behaviours. In the trainer's mind, the diversion of instinctive postures, when properly practiced and repeated well, can help to stage a boxing match "for fun". It involves training two talented performers, first alone and then together, and getting them used to standing in extension on their hind legs, like a horse coming back at the end of a presentation in the wild. The last difficulty to overcome finally, with rewards, will be to train it to wear boxing gloves to represent a parody that is both naïve and without glory.

Multi-card horse

A complete circus artist, why shouldn't the horse be an acrobat? Strangely enough, master trainers like André Rancy, Jean Houcke or Jules Glasner make horses climb on large wooden cylinders that they turn while walking. The tradition of "rubber" horses, which twist with their front legs, continues until the 20th century under the watchful eye of male and female trainers, including Diana Rhodin from the Swedish Circus Brazil Jack or Alexis Grüss in the ring of the Cirque à l’Ancienne. From acrobat to daredevil, some take the plunge. In 1850, Louis Soullier flew over the Hippodrome de Lyon, on a horse strapped under the large Philadelphie hot air balloon. Blondin, Corradini's tightrope horse, tragically ends his career as an "aeronaut horse" by falling with his rider from a platform stowed under a hot air balloon. Women, who are good riders, take over from these "follies".

In Lyon, in 1903, Joseph Bureau's horse, Tartarin I, played the drum, bells and piano. At Cirque Rancy, Alphonse Rancy places his "music-loving horse" in front of a device of crystal balls from which it obtains a simple melody by touching them with the tip of the hoof.

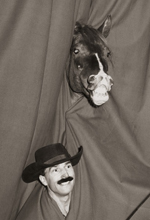

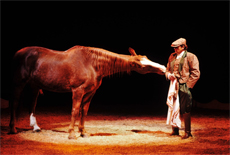

A joker, Astley's horse, Dick Turpin, named after the big-hearted robber who defies the armed forces in England, messes up a spectator's hair as it snatches her hat with its teeth and brings to another a lace handkerchief hidden in the sand of the track. Rosaire, Glasner, Rossi, renew their traditional repertoires by making their complicit horses perform "tricks". A versatile trainer, the Austrian Anton, known as "Toni" Hochegger, finally built his reputation on a small comic piece performed in duet with his partners, Jacket, then Pascha: the horse's bedtime. The recalcitrant animal finds excuses to avoid obeying the injunctions of its master who insists on making it lie down in a bed, pull up the blanket and close its eyes on the pillow. Patrick Grüss's is retracting carpets and saddles that he slides from his back with its teeth and pushes its master when the latter turns to the public for support. In the vein of the Tailleur de Brentford, a satirical piece created by Philip Astley during a local election in 1768, Sabine Rancy imagined associating the horse Dynamite, trained by Dany Renz, with the cause of circuses relegated to the outskirts of cities. The 1973 show ended with the horse laughing its teeth out as he kicked out of the ring and out of the way a barrier man dressed as a police officer "mandated" to dismantle the big top. Often overwhelmingly anthropomorphic, the horse is in line with the expectations of trainers who are keen to diversify their presentations. But we can prefer the vision of Bartabas, director of the Théâtre Equestre Zingaro, when he "abandons" his horses to their destiny as freed creatures, and steps aside as a trainer thanks to the creation in 2017 of Ex Anima, one of the most important shows of the decade.